NORWAY (World Soccer)

ì

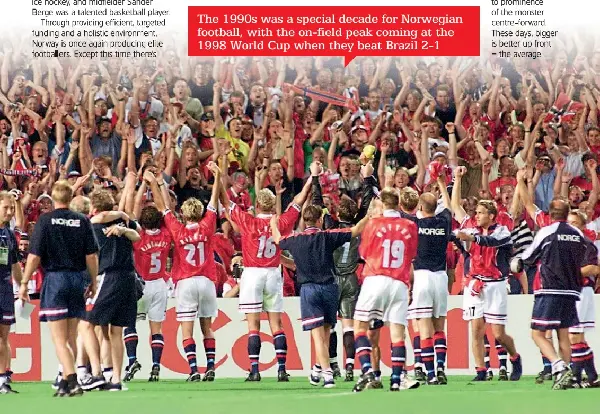

The 1990s was a special decade for Norwegian football, with the on-field peak coming at the 1998 World Cup when they beat Brazil 2-1

It has been a quarter of a century since Norway last appeared at a major international tournament, but their fleet of top-class forwards are leading them out of the footballing wilderness, writes Josh Butler

Josh Butler

1 Oct 2025 - World Soccer

In February, Norway and Manchester City striker Erling Haaland got involved in promoting a new line of Oasis merchandise ahead of the band’s long-awaited return. As the summer began, and nineties nostalgia gripped the UK, it was not just Mancunians in bucket hats that were dreaming of recreating the events of 30 years ago. In June, Haaland was on the scoresheet as Norway thumped Italy 3-0 in a World Cup qualifier to give them a golden opportunity of reaching the global finals for the first time since 1998.On the rise… Norway’s players ahead of a 2026 World Cup qualifier

The 1990s was a special decade for Norwegian football. Coached by Egil Olsen and subsequently his tactical disciple Nils Johan Semb, the national team rose to an all-time high of second in the FIFA world rankings in 1995, with the on-field peak coming at the 1998 World Cup when they beat Brazil 2-1. Indeed, Norway are one of the few nations to have never lost to the Selecao in their history.

As a footballing nation, Norway became famed for their athleticism and directness. Their players were big, strong and disciplined. “A vaere best uten ball” (“to be the best without the ball”) was Olsen’s philosophy. But those halcyon days are but a distant memory now. The Premier League stalwarts that formed the formidable back-line – Ronny Johnsen, Henning Berg, Stig Inge Bjornebye and Gunnar Halle – are long retired.

In the two decades following their Euro 2000 group-stage exit, the Norwegian FA (NFF) have tried just about everything to return the country to an international tournament. They’ve been through six managers to varying degrees of success, and attempted to adopt several philosophies of the zeitgeist from tiki-taka to high pressing.

In the last ten years though, the NFF has sought to make use of the most powerful tool at its disposal: money. Norway is a tremendously wealthy country and, when it comes to sport, the country has learned how to spend effectively.

Rather than directing finances towards the elite end of the game, grassroots footballing facilities have instead witnessed enormous levels of development. There are now more than 1,000 artificial football pitches in the country, and this proliferation of all-weather surfaces has been a significant factor in contributing to youth development, allowing academies to train their squads even during the harsh winters.

The other defining tool in the forging of Norway’s new golden generation concerns the social factor of sport. The Norwegian approach to sport is one of patience, community and fun; as of 2024, 93 per cent of children and teenagers participated in at least one sport. The maintenance of league tables is banned in the children’s game in order to promote playing for enjoyment, while the somewhat British mentality of picking a sport and dedicating your life to it is almost unheard of. Children, particularly those from middle-class backgrounds whose parents can afford entry into the best academies, are encouraged to pursue interests across a broad range of activities. Haaland, for example, participated in athletics and handball, Jorgen Strand Larsen played ice hockey, and midfielder Sander Berge was a talented basket ballplayer. Through providing efficient, targeted funding and holistic environment, Norway is once again producing elite footballers. Except this time there's one noticeable difference: while the Norwegian teams of the 1990s were built on their defence, the Norway of today runs a conveyor belt of forwards.

BELOW: Peak years …Norway players

celebrate with their fans at France ’98

Between them, the three senior national team strikers, Haaland, Strand Larsen and Alexander Sorloth, scored 119 goals in top European leagues in the previous two seasons. For context, that’s more than all seven of the Spain forwards called up by Luis de la Fuente in September put together.

Part of the success of these three strikers is due to the return to prominence of the monster centre-forward. These days, bigger is better up front - the average height of the starting Premier League forward now stands at 189cm – and Norwegians are bigger than most.

Not that Haaland, Sorloth and Strand Larsen are carbon copies of one another. Despite all three standing well over 190cm, there are subtleties to their games. Haaland is a prolific runner and elite finisher. At Borussia Dortmund, his monstrous pace was perfect for expediting counter-attacks against defences that had pushed too far upfield; under Pep Guardiola at Manchester City, he has become a world-class penalty-box poacher.

Sorloth, on the other hand, has spent much of his career as the support act, utilising his huge frame to assert aerial superiority and function as an archetypal target man. In recent years, he has added goals to his game. In the last two seasons, at Villarreal and then Atletico Madrid, he scored 43 goals in La Liga, even without being a regular starter for Diego Simeone’s side. During that time, only Barcelona striker Robert Lewandowski scored more times in the Spanish top flight.

Strand Larsen, five months older than Haaland yet still the junior partner of the trio, occupies the middle ground. Not quite as quick as Haaland and not quite as strong as Sorloth, he is a perennial 18-yard box merchant. His debut campaign in the Premier League saw him net 14 goals for a struggling Wolverhampton Wanderers side thanks to his crisp movement, diligence and ability to run across defenders.

Probing deeper, Haaland, Sorloth and Strand Larsen all share similar backgrounds that have contributed to their successes in the game. Famously, Erling is the son of Alf-Inge Haaland, a former professional footballer, and heptathlete Gry Marita Braut, but Sorloth is also well known in his home country as the son of former national team player, striker Goran Sorloth. Both of Strand Larsen’s parents were accomplished strikers too: his father, Atle, is the record scorer for Tistedalens TIF and his mother, Vibeke, the top scorer for Kvik Women.

These players have been bred for success, and the result is a depth of attacking talent that Norway has not seen since Euro 2000. The squad that travelled to the Netherlands and Belgium featured four players that are still among their all-time top ten goalscorers – Ole Gunnar Solskjaer, Tore Andre Flo, Steffen Iversen and a young John Carew – yet they crashed out at the group stage with only one goal scored (see right).

Unlike at Euro 2000, current coach Stale Solbakken has found a system that works for his strikers. Haaland operates as the indisputable number nine, with exciting young RB Leipzig winger Antonio Nusa on the left flank, and Sorloth slotting in wherever he’s needed. At times he has occupied the right flank as a kind of false winger, given licence to drift infield or operate as a wide target man, while against weaker sides he plays directly alongside Haaland in a 4-4-2. As for Strand Larsen, he is firmly the back up: only seven of his 21 caps have come in the starting XI and four of those in friendlies.

Now Norway’s record scorer, Haaland long surpassed all four of those Euro 2000 forwards and has racked up 48 goals in just 45 caps following his fivegoal blitz against Moldova in September, while Sorloth already has 24, level with Carew, placing him joint-fifth in their alltime scoring charts. However, the duo must deliver at a major tournament to truly match the exploits of Solskjaer and Flo. They have an advantage over their predecessors in that there is more creativity around them, with captain Martin Odegaard in behind, Nusa to the left, and starlet Oscar Bobb, Benfica’s Andreas Schjelderup and teenage talent Sverre Nypan (more on page 44) waiting in the wings.

Most of them weren’t even born the last time Norway played at a major international tournament. For Haaland and Co., qualifying for the World Cup in North America next year is not about nostalgia, it’s about making their own history.

***

Steffen Iversen celebrates scoring the winner v Spain

EURO 2000

While younger Norway fans will rightly be excited by the current crop, those with longer memories will recall the ill-fated Euro 2000 campaign, when they were also blessed with a hugely talented crop of forwards.False dawn…

Head coach Nils Johan Semb included three established Premier League strikers in his squad with Ole Gunnar Solskjaer (Manchester United), Tore Andre Flo (Chelsea) and Steffen Iversen (Tottenham Hotspur) travelling to Belgium and the Netherlands, as well as emerging starlet John Carew, then on the verge of joining Valencia from Rosenborg.

It was undoubtedly Norway’s best forward line-up for a generation – Flo had proven to be a reliable goalscorer for Chelsea, Iversen was coming off the back of a career-high 17-goal campaign for Spurs, and Solskjaer was one of the most clinical finishers in the English game – and the signs were promising when they were all involved in a 1-0 win over Spain in the first game of the tournament.

Iversen, starting on the right of a front three alongside Flo and Solskjaer, headed home the winner. Yet that proved to be Norway’s only goal of the tournament – or indeed any other tournament this century. After a 1-0 defeat to FR Yugoslavia, they played Slovenia in the decisive final game, and could only draw 0-0.

Afterwards, supporters and pundits lamented the team’s ultra-defensive and over-cautious approach. But that wasn’t wholly true – after all, all four of the forwards started against Slovenia, with Flo and Carew up front and Solskjaer and Iversen on the wings – yet the team were painfully lacking imagination. To have collected maximum points against the group’s top seeds in the first game and yet still fail to progress was viewed as an abject failure, and a dreadful waste of Norway’s attacking talent.

Semb’s modern successor, Stale Solbakken, was on the pitch that day. Norwegians will be hoping that if they do get to the 2026 World Cup, he will have learned from those past mistakes.

Commenti

Posta un commento