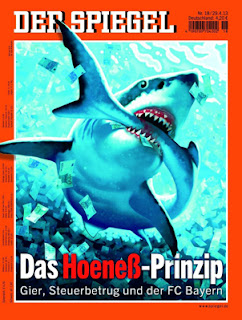

Bayern's Uli Hoeness - The Rise And Fall of a Soccer Saint

http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/bayern-president-uli-hoeness-may-end-up-in-jail-for-tax-evasion-a-897474-4.html

May, 01, 2013 06:35 PM

By SPIEGEL Staff

Uli Hoeness, the president of Bayern Munich and an icon of German club soccer, could end up behind bars for tax evasion. The case has highlighted the dark side of the skilful entrepreneur and philanthropist whose burning ambition made Bayern what it is today -- and has now triggered his fall from grace.

Although he is not sitting in jail awaiting trial, although he has not been convicted, although he can sit in a stadium dressed in a suit with a red-and-white scarf and can spend his nights at home, Uli Hoeness, the president of top German soccer club Bayern Munich, is already a prisoner. He is a prisoner of a small device -- not an electronic shackle or a beacon that informs the authorities of his whereabouts. The device is a receiver. It informs its owner of developments on stock markets around the world, and Hoeness can't stop himself from constantly staring at it.

The last thing he does before he boards an aircraft is glance at the stock market prices -- and it's the first thing he does after landing. He always wants to know how his investments are doing, whether he is winning or losing. Anyone who has such a device subjects himself to the power of the markets and becomes Homo economicus, a creature of capitalism. Hoeness is like that -- and since he is like that, he may soon have to go to jail.

This is how this story could end -- a news story first broken a week ago Saturday by the German magazine Focus when it reported that Hoeness was under investigation on suspicion of tax evasion. That news marked the wildest week in the 113-year history of the legendary club: tax evasion, an arrest warrant that was dropped after bail was posted, a sweeping 4:0 victory over FC Barcelona, the transfer of midfielder Mario Götze from Borussia Dortmund, Bayern's offer for Borussia Dortmund forward Robert Lewandowski. The ugly face of the elite Bavarian club has returned just when it's playing the most stunning football in Europe.

It was an abundance of drama for seven days. And on the eighth day, a week ago Saturday, the plot thickened. Key sponsors of Bayern Munich convened to talk about Hoeness' future. As a tax dodger, he doesn't fit with their corporate image.

The case quickly took on political overtones because Chancellor Angela Merkel of the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Bavarian Governor Horst Seehofer of its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU), frequently sought advice from Hoeness. "The first time I heard the allegations, I thought: This can't be true," says Seehofer in an interview with SPIEGEL.

Fall From Grace

Until 10 days ago, Hoeness was still a pillar of the community and a shining example for politicians. Now, he has fallen from similar heights as Margot Kässmann, the former head of the Protestant church in Germany, who was caught drunk driving -- and Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, the former defense minister, who was often named as a possible successor to Merkel, but was engulfed in a plagiarism scandal surrounding his doctoral dissertation that ultimately forced him to resign. It appears that Hoeness has joined the surprisingly large number of German luminaries who become mired in scandal.

Hoeness' story is inextricably intertwined with the history of Bayern Munich, the record-holding German team that has won the league title 23 times including this year, winning it six match days before the end of the season. The Bavarians have played so well that even non-fans have stopped hating them -- that doesn't happen often.

Indeed, the story of Hoeness and Bayern Munich can also be told as a minor tale of capitalism with all the right ingredients -- with competition, the performance principle, depravity, indignation, freedom and games, but above all, of course, with greed, with the endless desire to consume more and more. And since this is the German variety of capitalism, there are also social elements. Hoeness stands for all of this.

Hoeness is in a bad way. This once towering, robust figure has retreated to his home and can't make sense of what has happened to him. His home is his castle, and more important to him than ever. His wife Susi is at his side, and sometimes friends drop in for a visit. Hoeness has largely avoided speaking with the press, although he did grant one interview this week with Die Zeit, but there are ways of finding out what's going on with him.

He is furious. Who leaked the fact that he had turned himself into the tax authority? He has a right to anonymity like anyone else. The timing could hardly be worse -- in the final phase of the season, in the run-up to the important matches in the Champions League.

The fact that Merkel and Seehofer have so quickly distanced themselves has embittered him. He has always defended them, he says, and now this. Where is their sense of decency? Are the upcoming election campaigns more important than loyalty? He finds that callous and brutal.

Hoeness Feels Hard Done By

He reads a great deal in the newspapers and tries to understand it all. Guilty? No, not morally, he says. He didn't act in bad faith or criminally, he insists. He was probably simply given bad advice on tax issues, he says. He sees himself as a victim of circumstance, and his explanations revolve around a tragic series of events.

He was moved by the words of Bayern Munich chairman Karl-Heinz Rummenigge who, with the knowledge that Hoeness had turned himself in, nevertheless said he couldn't imagine Bayern Munich without him. Hoeness sees this as a grand gesture. Rummenigge may come to regret having made that statement.

Many aspects of this affair still remain uncertain. What is known is that it began in 2000. Hoeness cultivated a friendship with Robert Louis-Dreyfus, who was the boss of sporting goods manufacturer Adidas, which supplied the Bayern Munich kit. It was the era of the New Economy and boundless stock market fever -- the first eruption of unchained capitalism after the collapse of communism. Anyone could play the capitalist game. Buy and sell, calls and puts -- it seemed like everyone could get rich, and many people gambled like mad.

Hoeness wanted a piece of the action and Louis-Dreyfus give him 5 million marks (€2.56 million/$3.35 million) -- as play money, so to speak. It was deposited in a securities account with the number 4028BEA at Bank Vontobel, a Zurich financial institution known for its discretion. Subsequently, the bank reportedly granted Hoeness a loan amounting to 15 million marks, for which Louis-Dreyfus also acted as guarantor. Hoeness apparently gambled heavily with the money -- primarily on shares and currency exchange rates.

Today, Hoeness is sometimes described as a junkie, as a man who spent entire nights sitting in front of the TV in his hotel room to track stock market prices. "His stock market transactions run the gamut between riches and ruin," says one man who knows him well. "Other people go to casinos for that."

Gambling is one of the basic principles of capitalism, which is why it's often explained with game theory. It's not much different from playing poker. People speculate and bet on uncertainties -- the hidden cards, the vagaries of tomorrow's stock market. The appeal lies in the prospect of winning a fortune overnight, but also in the adrenaline-pumping fear of making huge losses. Hoeness apparently became addicted to the thrills, which isn't a crime. But it is illegal not to pay taxes on the winnings from such gambling.

Someone who is in a position to know says that Hoeness decided back before Christmas to turn himself in to the tax authorities, but then came the holidays, and his tax consultant went on vacation for two weeks. A great deal depends on whether Hoeness can prove this.

In early January, Bank Vontobel phoned Hoeness to say that someone from Germany's Stern magazine was doing some research on a celebrity from the sports sector: "Somebody is asking some stupid questions, just so you know." Hoeness reportedly flew into a rage and demanded that his tax accountant quickly write a voluntary declaration of tax liabilities.

On Jan. 12, Hoeness' letter arrived at the tax office in the southern German town of Miesbach. The sender was not a criminal tax lawyer, but rather Hoeness' long-time tax advisor Günter Ache, 65, who has his office in northern Germany. They met in the 1980s while skiing in Switzerland. Ache has an outstanding reputation as a tax consultant, but voluntary declarations are tricky. If it concerns speculation on the stock market, all purchases and sales have to be declared in detail. If an error is made, it dashes all hopes of avoiding a conviction.

Tax Authority Hands Tax Return to Prosecutor

Hoeness' text was rather sloppily written. For a number of years, he netted out his gains and losses from shares and currency dealings, which is not allowed. "A beginner's mistake," says a leading Munich criminal tax lawyer.

Hoeness made losses for two to three years, and calculated this as a negative balance. This is also not allowed. Not surprisingly, the tax authorities found that Hoeness' declaration was insufficient. They transferred the tax dossier to the Munich public prosecutor's office, which by Feb. 1 launched an investigation into Hoeness on suspicion of tax evasion and, in mid-March, searched his villa high above Tegernsee lake, a resort area in the Bavarian Alps. The officials presented a search warrant and a warrant for his arrest. Hoeness paid €5 million in bail, allowing him to continue to enjoy his freedom.

Since then, Hoeness has revised his voluntary declaration, which was said to be plausible, but not sufficiently detailed. Prosecutors are reportedly satisfied with the subsequently submitted version, but this no longer has any influence on the question of immunity from criminal prosecution. The public prosecutors calculated that Hoeness owed back taxes of €3.2 million, which he promptly paid. But now they want to know why a very large amount of money was temporarily deposited in his bank account. During a currency transaction, over €20 million reportedly accumulated in the account. Hoeness has yet to comment on this.

Sources within the judiciary say that investigators took such a hard line because they have a bone to pick with Hoeness. In Sept. 2011, after consuming copious amounts of alcohol, Brazilian player Breno, who was 21 years old at the time and a Bayern Munich defender, set fire to his rented villa in the affluent Munich suburb of Grünwald and was arrested. Hoeness was outraged at this treatment by the authorities and launched into a public tirade: "What the Munich public prosecutor's office is doing is an absolute disaster! Issuing an arrest warrant against a young man who is completely devastated, with the ridiculous justification that he may be suppressing evidence -- he can't speak any German!"

Later, he regretted making this comment. "My biggest mistake was to attack the public prosecutor's office. They didn't appreciate that at all," he said.

Jail Sentence Possible If the public prosecutor and the courts don't accept the late voluntary declaration, Hoeness may well have to go to jail. In 2008, the Federal High Court determined that for alleged tax evasion sums of over €1 million, the courts generally can no longer issue a suspended sentence. Even if Hoeness' lawyers manage to push through as many as deductions possible, they will hardly be able to reduce it below the million-euro threshold.

In addition to possible tax evasion, the charges could also include bribery in business transactions -- if, that is, it doesn't already fall under the statute of limitations. Why did Louis-Dreyfus gave his friend millions to go on a gambling spree? Was it a small inducement to help pave the way for the hoped-for extension of Adidas' endorsement deal with Bayern Munich? The agreement was renewed in September 2001, although Nike would have paid significantly more.

It wouldn't be the first dubious business deal between Adidas and the Bavarians. In the spring of 2001, the record-holding championship team was negotiating the transfer of Peruvian striker Claudio Pizarro from Werder Bremen. Pizarro had scored 19 goals the previous season, so he and his manager were asking for $7 million net income for four years, plus a one-off net payment of $8 million.

Since the Bavarians apparently couldn't or wouldn't pay this much money, Adidas stepped in. Pizarro was given an eight-year advertising contract worth $21.6 million, which was precisely the amount needed to end up with $8 million after deducting all taxes. The deal included a confidential side agreement ("only two originals, no copies"), in which the Bavarians guaranteed the one-off payment stipulated by Pizarro.

'I'm Almost Hopelessly Ambitious'

Why does a club or an individual go to such lengths? One reason is competition, the underlying principle of capitalism. Nowhere is competition as demonstratively practiced as in sports. It's all about performance and rankings -- there are winners and losers, champions and teams that are relegated to lower divisions. The best should win, but in football this dictum is increasingly associated with the pronouncement that, in reality, only the rich can win. Virtually no one has grasped this as clearly as Hoeness, who has transformed Bayern Munich into a stronghold of sports capitalism. He is the ideal man for this kind of system.

Hoeness, whose parents ran a butcher shop in Ulm, in the southern German state of Baden-Württemberg, wanted to move up in life, right from the start. Moving up was all about acquiring money, wealth and a large, successful business -- unlike his father, who never expanded his shop, and closed up the place if five pfennigs were missing from the cash register, and only reopened for business when the money was found. Football was one way of moving up. "I'm incredibly, almost hopelessly ambitious," Hoeness once said of himself.

There were bigger talents in German football in the late 1960s, but none of them were driven by such determination. Hoeness told his father to wake him up every morning at 5:30 a.m., so that he could go jogging before school. Out on the pitch, he rarely picked his brother Dieter to play on his own team because he felt he would jeopardize their chances of winning. Later, Dieter Hoeness went on to become a successful center forward, and spent part of his career at Bayern Munich.

Losing was the worst thing that could happen to Hoeness. He took it as a personal insult. When he was 15, he said to a teammate at TSG Ulm: "Look, the others are off to drink beer, and we'll play for Bayern Munich someday." Three years later, he was in a team with legendary players like Franz Beckenbauer and Gerd Müller. At the age of 20, he helped the team become European champions, at 22 he was on the West German national team that won the World Cup in 1974. He also took home the UEFA Cup Winners' Cup three times.

After the World Cup in 1974, Hoeness sold 300,000 books within just a few months, and personally signed each copy. He offered his wedding to the media -- for 75,000 marks. He posed for a menswear company in hot pants and with a bare torso. He opened up his half of a duplex to a tourist group, pulled on a pair of oven mitts and served them Leberkäse, a Bavarian meat specialty that's similar to boloney. He was a new kind of professional athlete, one who strove to turn every occasion into a money-making opportunity. After friendly matches, coach Dettmar Cramer would often say: "Gentlemen, I leave you in the hands of Uli here, you can settle everything with him!"

General Manager of Bayern at 27

An injury to his right knee put a stop to his meteoric career. At the age of 27, Hoeness became the general manager of Bayern Munich. "I put on a tie, sat down at a desk and after three hours there was nothing more to do," is how Hoeness described his first day at work. At the time, in 1979, Bayern Munich was a different club. It was 7 million marks in debt and the golden days were over, with Beckenbauer in the United States and Müller on his way there.

But Hoeness confided in his pal Paul Breitner that he would turn this scrap heap into "a new Real Madrid."

At best, it became a poor reflection of the elegant Spanish team. For decades, the team's style of play had remained relatively unrefined. Once they scored a goal, they would play a defensive, boring game to hold the score, led by football warriors like Klaus Augenthaler. With obvious delight, Hoeness snatched up the best players from other teams in the Bundesliga. In the early 1990s, when Karlsruher SC valiantly fought their way to the top of the first-division standings, they were practically bought up lock stock and barrel by Bayern Munich. One after the other, Michael Sternkopf, Oliver Kreuzer, Mehmet Scholl and Oliver Kahn transferred to Munich, followed later by Thorsten Fink and Michael Tarnat.

Hoeness struck another blow to his rivals' ability to compete in early December 1999. At the time, he signed a secret agreement with the Kirch media group, which operated TV stations Sat.1 and Premiere, which broadcast Bundesliga games back then. The contract secured the Bavarians the equivalent of some €15 million a year for the first three years. Starting in 2003, this amount was supposed to increase to €40 million. The reason behind the highly confidential agreement was that Bayern Munich had agreed to the central marketing of TV broadcasting rights by the League Commission. Back in the summer of 1999, the Bavarians had still insisted on being able to market their TV broadcasting rights themselves in the hope that this would significantly boost their revenues.

This plan failed due to resistance from other clubs. The Bavarians acted as if they were prepared to make concessions, but then signed the secret contract. Up until 2002, when the Kirch media group went bankrupt, some €20 million were deposited on account 6105308 owned by FC Bayern Sport-Werbe GmbH at the club's principal bank, Hauck & Aufhäuser.

'We Have to Become More Arrogant'

Later, in 2000, Hoeness argued before the League Commission in favor of accepting an offer by Kirch for the awarding of broadcasting rights, although at the time a considerably better offer was made by a rival. An assessment by Lovells law firm on the issue came to the conclusion that the Bavarians under Hoeness had been "bought" by the Kirch group.

His at times contemptible manner of beating the competition was often accompanied by notorious comments such as this: "We're going to slaughter our opponents." No wonder the rest of the country hated Hoeness and Bayern Munich. And Hoeness? He loved it. He said: "We have to become more arrogant." On the side, he set up a sausage making factory.

Success at any price -- that was one side of Hoeness. The other side was that of a patriarch who looked after his people. He made Bayern Munich into a family firm, although the core family still remains the team from the 1970s: Beckenbauer, Rummenigge and Breitner. Hoeness personally oversaw the alcohol detox of Gerd Müller, who found himself stranded in faraway Florida.

It's a two-faced kind of capitalism that reigns in Munich, on the one side brutal and arrogant, on the other dependable and caring. The club doesn't gamble with its funds and it doesn't have debts. In fact, it has €100 million in the bank and a stadium that will soon be paid off. A good 80 percent of FC Bayern belongs to its members, with Adidas and Audi each holding 9 percent. This is a team without a trace of Chelsea's oligarch, of the consortium of sheikhs that rules Paris Saint-Germain and Manchester City, or of Manchester United's US business tycoon.

Hoeness' FC Bayern is in perfect health, and that's one reason it's been able to draw someone like Pep Guardiola, considered the world's best soccer coach since his time with FC Barcelona. Guardiola picked a respectable team run by respectable people -- or at least so he thought when he agreed this winter to join FC Bayern.

Hoeness knew what was coming at that point, yet he continued to play his new role, that of the good, wise man who tells everyone how to live an orderly life and how to do sensible business. A SPIEGEL reporter accompanied Hoeness during those weeks in which he was simultaneously two different people. One side of Hoeness was the respectable soccer team manager and sausage factory owner. The other was the tax evader Hoeness, the man who had already turned himself in, the man who was later arrested and remained at liberty only in exchange for a hefty bail, still having to report twice a week to the police.

And all the time this was going on, Hoeness was hoping the public wouldn't catch wind of any of it, allowing him to maintain his image as a moral authority. Hoeness liked being described as a role model. It's unclear whether he was even fully aware of the double life he was leading, or if at some point he stopped noticing the contradiction between the public figure and the private citizen.

Chatting With Merkel On Jan. 12, a Saturday, Hoeness filed a voluntary disclosure of his tax evasion. Three days later, he took an early morning flight to Berlin to participate in a board meeting of the Germany Integration Foundation, an organization that aims to promote the integration of immigrants. Chancellor Merkel had called him personally beforehand to ask if he would like to be present, and expressed her high regard for Hoeness.

After the meeting, Hoeness sat down for a coffee with Merkel at the Chancellery. It was a pleasant meeting as always with the chancellor, a stimulating talk, Hoeness said the next day, adding that he finds Merkel highly intelligent, with incredibly quick comprehension. He added, "She said to me, Mr. Hoeness, we are going to have to play soccer in Europe now, 90 minutes, perhaps even 120 minutes. But I hope we don't have to go into a penalty shootout, because Bayern isn't very good at that."

Hoeness made these comments about Chancellor Merkel from his office at FC Bayern Munich's headquarters on Säbener Strasse in Munich on Jan. 16, four days after he had filed his voluntary disclosure with the tax authorities. On the desk in front of him lay an invitation from a company asking him to give a talk at a company party. Hoeness picked up the invitation and read aloud, "You have demonstrated that it is important, in addition to taking economic responsibility for employees and clients, never to lose track of social and societal responsibility as well."

Setting the letter back on his desk, Hoeness declared, "That says it all." He has always moved through the world with his eyes and ears open, Hoeness continued, adding that he is someone who "just understands how society works." He said, "People like me, who are fairly independent economically and very successful, increasingly need to assume social responsibility as well. These days no one is going to accept that you earn more money than many others unless you think for others as well."

Hoeness sounded very committed and convincing as his spoke. At the same time, his gaze wandered constantly to his TV. The sound was off, but the screen showed teletext from broadcaster n-tv with the latest stock market indexes.

Eight days after his voluntary disclosure, Hoeness was invited to the Bavarian town of Peissenberg, where the local branch of the CSU was holding its New Year's reception. Local party chair and CSU secretary general Alexander Dobrindt, who had issued the invitations, stood in the foyer, and seemed as excited as a little boy.

'You Have To Be Credible'

Onstage and in the best of moods, Hoeness explained what he felt was going well and what badly in Germany. He spoke confidently, giving the impression of being someone who understands what's going on and whom someone politicians should listen to more often. "These days, whether you're part of a club or part of politics, you have to go your own way, you have to have a clear concept and you have to be credible," Hoeness said.

Yet there were moments of hidden honesty that day as well. In Peissenberg, Hoeness fielded a question about left-wing politicians' plans to increase taxes on wealth and on high incomes by responding, "There are certain limits beyond which citizens are simply no longer willing to keep doing even more for others." It is a mistake, he added, to believe that "if we keep taking more and more from the wealthy, then things will be better for those with less. That's simply not the case. In fact, the opposite is true! If the wealthy eventually have had enough and decide to do less, then those with less will have to start working more again, to be able to maintain the status they currently have."

During the trip to Peissenberg, Hoeness proudly mentioned that his going rate for such talks has reached over €25,000 and that he donates every euro of that to charitable organizations. He expressed his disdain for the center-left Social Democratic Party's candidate for chancellor, Peer Steinbrück, who keeps his honorarium for himself.

Evading Taxes but Donating to Charity

That same evening, Hoeness gave hundreds of insurance agents a talking to. "The way I see the responsibilities of companies and of people is that those who are doing especially well have a damn responsibility to society, a responsibility to give those who aren't doing well a helping hand, in the hope that they will seize that opportunity and soon become full members of society once again," he declared.

That statement sounds as if it stands in direct contradiction to Hoeness' tax evasion -- since the very idea of taxation is that a government uses that revenue to give those who aren't doing well a helping hand -- and yet it isn't a contradiction. In fact, one could say the theoretical figure described in 2009 by philosopher Peter Sloterdijk finds a real-life counterpart in Uli Hoeness.

Central to the philosophy Sloterdijk describes is the idea of government as an enemy of freedom, and freedom as the highest commodity in capitalism. Adherents of this philosophy don't believe they live in a market economy, but rather "in an order of things that must be defined, though with a grain of salt, as semi-Socialism based on a foundation of private property, animated by mass media and drawing on government taxation," Sloterdijk writes. They feel they are at the mercy of a "government kleptocracy," a "monster that keeps taking," and that the most feasible response to this is an "anti-fiscal civil war." Sloterdijk suggests that instead of paying taxes, the wealthy should donate their money to "societally beneficial entities of their choice."

A major topic in a SPIEGEL interview with Hoeness last fall was the ill will he has sometimes caused at the club when he has revealed internal matters in these talks he gives, or when his witty critiques of everything under the sun have overshot their mark. Hoeness explained very earnestly that he has to do these things, because that's what people want to hear, and that if he didn't, companies wouldn't pay so much money for his appearances -- money, he pointed out, that he gives to charitable causes. The world would be a poorer place, in other words, without Hoeness' frivolous comments. He seems to truly believe that by doing the talk circuit and collecting donations for it, he is making the world a better place.

That attitude explains the strange coexistence of evading taxes but donating generously. It's not so much a matter of keeping all the money for oneself, but rather of keeping that money away from a government that can't be fully trusted. Hoeness certainly isn't alone in his skepticism toward the government. No one wants to pour their money into a bureaucracy if they harbor doubts as to whether that bureaucracy will handle the money well. Fortunately, though, not everyone reacts by resorting to illegal methods, as Hoeness has done -- while most likely allaying his conscience with the donations he has made. Those who do good things find it easier to do bad things as well, because they're able to tell themselves that they are essentially good people.

Much the same can be said of people who achieve great things. They sometimes tend to award themselves privileges and allow themselves not always to follow rules and laws. They see this special status as a reward for their great achievements.

A Duopoly in the Bundesliga Perhaps Hoeness takes such a perspective as well. Didn't he lead Bayern back to its spot among the top European teams, all while being good to his German competition? Didn't he give Borussia Dortmund a loan when the club was nearly bankrupt, and grant impoverished FC St. Pauli a benefit match to help that team stay afloat? Yes, he did. But then something unnerving happened to Bayern: In the last two years, Borussia Dortmund won the Bundesliga. Some sport analysts already speculate the team may become the new dominant force in the Bundesliga, the monopolist of success.

Bayern reacted to that news by making a few smart purchases of players and has so far dominated the league in the current season. But it seems that wasn't enough. Hoeness himself also made a few moves that wouldn't be out of character for Gordon Gekko, that ultimate capitalist from the movie "Wall Street."

In mid-April, Hoeness suddenly began an assault on the so-called "Spanish conditions" supposedly threatening the Bundesliga. After Bayern won 4-0 against Nuremberg on the same day that Dortmund beat Greuther Fürth 6-1, FC Bayern president announced he saw "a need to take action" and that "such results aren't acceptable in the long term." He also said had already spoken about the matter with Dortmund's business manager Hans-Joachim Watzke.

The term "Spanish conditions" refers to the way FC Barcelona and Real Madrid have formed essentially a private society for the superrich and super strong, sharing between them around 60 percent of the Primera División's total sales, as well as its titles. This is very different from Germany's Bundesliga, whose trademark is the constant excitement of not knowing who will win, following the motto that anyone can beat anyone -- although that hasn't been strictly true for the last three years. The question, then, is whether Germany is on its way to becoming a Spanish-style duopoly dominated by Dortmund and Bayern Munich.

When Hoeness laid out his idea, Watzke wondered how it would work. Was Hoeness volunteering to donate players -- or even funding -- to struggling members of the competition? The distribution of national television funding for the next four years was decided in November 2012, and Bayern has certainly complained about the ample earnings that go to the Champions League's top teams. Besides, Watzke believes, more equality within the sport would come at the cost of quality, since German teams capable of keeping up with top teams around Europe will have to dominate the national league.

Watzke was thus taken by surprise when he read about his telephone conversation in the newspaper -- Hoeness had gone public with the idea. Was that the Bayern manager's plan all along? Did Hoeness want to garner acclaim for himself as the lone do-gooder, the champion of solidarity within the Bundesliga, the socialist of soccer?

'He Wants to Destroy Us'

Hoeness has since backpedaled on his plan. It turned out to be hypocritical in any case, since Hoeness must have known, even as he was supposedly campaigning for more equality, that his team had plans to snap up Dortmund's wunderkind Mario Götze. That deal went through for €37 million, because that's the price the player -- or more accurately his advisor -- and Dortmund established in a release clause in Götze's contract. And because it's a price FC Bayern was able to pay.

Now Dortmund is spreading rumors that it was not FC Bayern as a club, but rather Hoeness working alone, who leaked news of the transfer to the mass-circulation newspaper Bild, in order to unsettle Dortmund just before the first leg of the team's semi-final match against Real Madrid last week. According to the rumors, Hoeness was desperate to prevent his absolute worst-case scenario, which is that Bayern might lose to Barcelona in the semi-final and that Dortmund win the Champions League. A Borussia official says of Hoeness, "He wants to destroy us." Hoeness, meanwhile, denies he was the leak. All sides here are playing hardball.

Bayern would also dearly love to snatch away Dortmund's striker Robert Lewandowski, doubly weakening its rival team. The competition believes the Bavarian team has long since agreed with Lewandowski on a transfer -- although such an agreement is against regulations -- by the season after next at the latest, at which point the Polish striker will be a free agent. If Lewandowski wants to transfer before that, he will need Dortmund's consent, but the team has no interest in approving an early transfer, not after Götze -- and not even for the €25 million Bayern is said to be willing to pay for Lewandowski.

Modern capitalism, too, began with the trade in human beings, in the form of slavery. Some people may never get used to the idea that athletes have a price tag and can be traded back and forth. But that trade is by no means the specialty of Bayern Munich alone. Bayern buys Götze from Dortmund, Dortmund buys Marco Reus from Mönchengladbach, Mönchengladbach buys Max Kruse from SC Freiburg, and so on. Bayern Munich is such a successful team precisely because it understands this business so well -- thanks to Hoeness.

Not everyone is able to come to terms with this free-market form of soccer. There will always be hardliners in the stadiums who manage to cling to the dream that their sport is first and foremost about heart and soul, about football, about a particular city. When goalkeeper Manuel Neuer transferred to Bayern in 2011 from Schalke 04, the Bundesliga team of the western industrial city of Gelsenkirchen, that went too far for many fans. Neuer was a real Gelsenkirchen boy, who had himself shouted his heart out in the stands, cheering for the home team, before he followed the scent of money and success to Munich. Schalke's hardcore fans were outraged at Neuer's perceived betrayal, while Munich fans reacted with hostility to their team's new purchase. This wasn't the kind of player they wanted.

Now all that is forgotten. Soccer has a great power to reconcile, and the name of that power is success. When Bayern Munich plays as enchantingly well as it has done this season, even diehard Bayern haters find themselves enamored with the team for the beauty of its game, for the joy of a successful combination ending in an exquisite goal, for the intoxication of a match well played. When that happens, no one is thinking about the trade in humans, because consumption always makes it easier to reconcile ourselves with capitalism. Consumption is good at creating illusions. We see the lovely picture on the surface and not the system behind it.

Tepid Support From Bayern Fans

Tax fraud, though, has a way of seriously disrupting that illusion. At Bayern's game against Barcelona last Tuesday, fans showed far less support for Hoeness than expected. One fan held up a small sign that read, "Uli, I'm sticking by you." When, during the halftime break, the stadium's video screen showed a shot of Hoeness cheering for a goal, the audience clapped a bit, but the atmosphere remained strangely cool and no chants rose up in support of Hoeness.

Does this mean that a soccer stadium is a hotbed of government supporters, people who want to make sure their politicians have plenty of money to work with? Hardly. But Germans are touchy when it comes to questions of justice. They have no sympathy for someone who has a lot to begin with, and then commits fraud in order to have even more. Tax fraud is a phenomenon of the wealthy. For someone drawing a normal salary, as the majority of the fans in the stands do, withholding money from the government is never even an option. In that sense, it can seem unfair that some people even have the option of committing fraud, while others don't.

The people who reacted most strongly, though, were seated comfortably in the VIP section, especially Martin Winterkorn, CEO of Volkswagen, and Rupert Stadler, CEO of Volkswagen's subsidiary Audi. Both men sit on Bayern Munich's supervisory board and will have a say in deciding Hoeness' future.

The football manager now finds himself at the mercy of a different aspect of capitalism -- a global company with a built-in obsession with being scrupulously correct to protect its reputation, especially after a major sex and corruption affair tainted the company in 2005. A major corporation such as this one has a particular interest in being clean so that customers don't get angry with it and stop buying its products. An Audi car cannot afford to be connected in any way to the word "fraud," and it is Audi that provides FC Bayern's vehicles.

The company's top managers always saw Hoeness as a soccer saint. Winterkorn has known Hoeness for over 10 years, since the partnership between Audi and Bayern Munich first began. The idea back then was that some of the soccer team's glamor would rub off on an automobile brand that was looking a bit wan at the time. Winterkorn also sought Hoeness' advice when he needed to hire a new coach for VfL Wolfsburg, the team Volkswagen owns.

'Hoeness Will Have to Go'

The revelation of Hoeness' tax evasion surprised and saddened Winterkorn, those close to the CEO say. They say Winterkorn has made comments such as, "He's messed it up," and "Anyone who points fingers at others has to be unassailable himself."

A manager who withheld several million euros in taxes would certainly not be allowed to keep his position at Volkswagen, at least not if the case became public knowledge. And Bayern Munich is technically a VW holding, since Audi owns just under 10 percent of the club, which means the carmaker's rules must hold for the soccer club as well. The result, say those around Winterkorn and Stadler, is clear: "Hoeness will have to go."

Members of the club's supervisory board are also annoyed that they weren't informed about the search of Hoeness' villa and the warrant for his arrest before the media were. "Then we could have been prepared, not caught off guard," they say. The board is eager to talk with the team's other major sponsors, Deutsche Telekom, Adidas and Allianz.

At a meeting on Saturday, for which Winterkorn cancelled a visit to a VfL Wolfsburg home game, board members agreed that if Hoeness isn't willing, at the supervisory board meeting next Monday, to announce his resignation or at least to step aside for a period, then the board will force him to do so.

Then again, Volkswagen itself isn't particularly well placed to condemn Hoeness given that VW managers face a lawsuit for incorrect business practices in connection with VfL Wolfsburg. It turns out all isn't clean and correct in the world of corporate management either. But here, too, companies are eager to peddle an illusion.

As for Bayern, some insiders believe Franz Beckenbauer will now make a comeback. When Beckenbauer made way for Hoeness as supervisory board chair in 2009, he didn't do so entirely of his own free will. The foundation for that change was laid during the 2006 World Cup, while Beckenbauer was too busy to keep a close eye on his power base at Bayern. Sometimes rivals within family businesses fight particularly tough and dirty.

Capitalism can also be seen as a system of temptations, in which there are countless temptations to do something bad, because something that's bad for someone else so often appears to be good for oneself. Hoeness, for all his good deeds, was not especially good at resisting this temptation. It turns out words he himself spoke in a 2002 interview are true: "It doesn't make any sense to end up in prison over a few deutsche marks in taxes."

REPORTED BY DINAH DECKSTEIN, MARKUS FELDENKIRCHEN, MAIK GROSSEKATHÖFER, DIETMAR HAWRANEK, THOMAS HUETLIN, JÖRG KRAMER, DIRK KURBJUWEIT, CONNY NEUMANN, JÖRG SCHMITT, MICHAEL WULZINGER

Translated from the German by Paul Cohen and Ella Ornstein

URL:

http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/bayern-president-uli-hoeness-may-end-up-in-jail-for-tax-evasion-a-897474.html

Related SPIEGEL ONLINE links:

Photo Gallery: Greed, Tax Evasion and FC Bayern Munich

http://www.spiegel.de/fotostrecke/photo-gallery-greed-tax-evasion-and-fc-bayern-munich-fotostrecke-96199.html

High-Profile Catalyst: Tough Times Ahead for German Tax Evaders (04/30/2013)

http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/uli-hoeness-case-tough-times-ahead-for-german-tax-evaders-a-897333.html

Election Risk: Hoeness Tax Evasion Case a Headache for Merkel (04/23/2013)

http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/analysis-of-impact-of-uli-hoeness-tax-probe-on-chancellor-angela-merkel-a-895947.html

Money Mountain: Swiss Banks 'Plundering German Treasury' (04/26/2013)

http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/sociologist-jean-ziegler-says-swiss-banks-plundering-german-treasury-a-896689.html

Soccer Icon Wobbles: Bayern Munich President Probed for Tax Evasion (04/22/2013)

http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/bayern-munich-president-uli-hoeness-faces-tax-evasion-probe-a-895769.html

Swiss Bank Data: German Tax Officials Launch Nationwide Raids (04/16/2013)

http://www.spiegel.de/international/business/germany-raids-200-suspected-tax-evaders-in-nationwide-hunt-a-894693.html

May, 01, 2013 06:35 PM

By SPIEGEL Staff

Uli Hoeness, the president of Bayern Munich and an icon of German club soccer, could end up behind bars for tax evasion. The case has highlighted the dark side of the skilful entrepreneur and philanthropist whose burning ambition made Bayern what it is today -- and has now triggered his fall from grace.

Although he is not sitting in jail awaiting trial, although he has not been convicted, although he can sit in a stadium dressed in a suit with a red-and-white scarf and can spend his nights at home, Uli Hoeness, the president of top German soccer club Bayern Munich, is already a prisoner. He is a prisoner of a small device -- not an electronic shackle or a beacon that informs the authorities of his whereabouts. The device is a receiver. It informs its owner of developments on stock markets around the world, and Hoeness can't stop himself from constantly staring at it.

The last thing he does before he boards an aircraft is glance at the stock market prices -- and it's the first thing he does after landing. He always wants to know how his investments are doing, whether he is winning or losing. Anyone who has such a device subjects himself to the power of the markets and becomes Homo economicus, a creature of capitalism. Hoeness is like that -- and since he is like that, he may soon have to go to jail.

This is how this story could end -- a news story first broken a week ago Saturday by the German magazine Focus when it reported that Hoeness was under investigation on suspicion of tax evasion. That news marked the wildest week in the 113-year history of the legendary club: tax evasion, an arrest warrant that was dropped after bail was posted, a sweeping 4:0 victory over FC Barcelona, the transfer of midfielder Mario Götze from Borussia Dortmund, Bayern's offer for Borussia Dortmund forward Robert Lewandowski. The ugly face of the elite Bavarian club has returned just when it's playing the most stunning football in Europe.

It was an abundance of drama for seven days. And on the eighth day, a week ago Saturday, the plot thickened. Key sponsors of Bayern Munich convened to talk about Hoeness' future. As a tax dodger, he doesn't fit with their corporate image.

The case quickly took on political overtones because Chancellor Angela Merkel of the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Bavarian Governor Horst Seehofer of its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU), frequently sought advice from Hoeness. "The first time I heard the allegations, I thought: This can't be true," says Seehofer in an interview with SPIEGEL.

Fall From Grace

Until 10 days ago, Hoeness was still a pillar of the community and a shining example for politicians. Now, he has fallen from similar heights as Margot Kässmann, the former head of the Protestant church in Germany, who was caught drunk driving -- and Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, the former defense minister, who was often named as a possible successor to Merkel, but was engulfed in a plagiarism scandal surrounding his doctoral dissertation that ultimately forced him to resign. It appears that Hoeness has joined the surprisingly large number of German luminaries who become mired in scandal.

Hoeness' story is inextricably intertwined with the history of Bayern Munich, the record-holding German team that has won the league title 23 times including this year, winning it six match days before the end of the season. The Bavarians have played so well that even non-fans have stopped hating them -- that doesn't happen often.

Indeed, the story of Hoeness and Bayern Munich can also be told as a minor tale of capitalism with all the right ingredients -- with competition, the performance principle, depravity, indignation, freedom and games, but above all, of course, with greed, with the endless desire to consume more and more. And since this is the German variety of capitalism, there are also social elements. Hoeness stands for all of this.

Hoeness is in a bad way. This once towering, robust figure has retreated to his home and can't make sense of what has happened to him. His home is his castle, and more important to him than ever. His wife Susi is at his side, and sometimes friends drop in for a visit. Hoeness has largely avoided speaking with the press, although he did grant one interview this week with Die Zeit, but there are ways of finding out what's going on with him.

He is furious. Who leaked the fact that he had turned himself into the tax authority? He has a right to anonymity like anyone else. The timing could hardly be worse -- in the final phase of the season, in the run-up to the important matches in the Champions League.

The fact that Merkel and Seehofer have so quickly distanced themselves has embittered him. He has always defended them, he says, and now this. Where is their sense of decency? Are the upcoming election campaigns more important than loyalty? He finds that callous and brutal.

Hoeness Feels Hard Done By

He reads a great deal in the newspapers and tries to understand it all. Guilty? No, not morally, he says. He didn't act in bad faith or criminally, he insists. He was probably simply given bad advice on tax issues, he says. He sees himself as a victim of circumstance, and his explanations revolve around a tragic series of events.

He was moved by the words of Bayern Munich chairman Karl-Heinz Rummenigge who, with the knowledge that Hoeness had turned himself in, nevertheless said he couldn't imagine Bayern Munich without him. Hoeness sees this as a grand gesture. Rummenigge may come to regret having made that statement.

Many aspects of this affair still remain uncertain. What is known is that it began in 2000. Hoeness cultivated a friendship with Robert Louis-Dreyfus, who was the boss of sporting goods manufacturer Adidas, which supplied the Bayern Munich kit. It was the era of the New Economy and boundless stock market fever -- the first eruption of unchained capitalism after the collapse of communism. Anyone could play the capitalist game. Buy and sell, calls and puts -- it seemed like everyone could get rich, and many people gambled like mad.

Hoeness wanted a piece of the action and Louis-Dreyfus give him 5 million marks (€2.56 million/$3.35 million) -- as play money, so to speak. It was deposited in a securities account with the number 4028BEA at Bank Vontobel, a Zurich financial institution known for its discretion. Subsequently, the bank reportedly granted Hoeness a loan amounting to 15 million marks, for which Louis-Dreyfus also acted as guarantor. Hoeness apparently gambled heavily with the money -- primarily on shares and currency exchange rates.

Today, Hoeness is sometimes described as a junkie, as a man who spent entire nights sitting in front of the TV in his hotel room to track stock market prices. "His stock market transactions run the gamut between riches and ruin," says one man who knows him well. "Other people go to casinos for that."

Gambling is one of the basic principles of capitalism, which is why it's often explained with game theory. It's not much different from playing poker. People speculate and bet on uncertainties -- the hidden cards, the vagaries of tomorrow's stock market. The appeal lies in the prospect of winning a fortune overnight, but also in the adrenaline-pumping fear of making huge losses. Hoeness apparently became addicted to the thrills, which isn't a crime. But it is illegal not to pay taxes on the winnings from such gambling.

Someone who is in a position to know says that Hoeness decided back before Christmas to turn himself in to the tax authorities, but then came the holidays, and his tax consultant went on vacation for two weeks. A great deal depends on whether Hoeness can prove this.

In early January, Bank Vontobel phoned Hoeness to say that someone from Germany's Stern magazine was doing some research on a celebrity from the sports sector: "Somebody is asking some stupid questions, just so you know." Hoeness reportedly flew into a rage and demanded that his tax accountant quickly write a voluntary declaration of tax liabilities.

On Jan. 12, Hoeness' letter arrived at the tax office in the southern German town of Miesbach. The sender was not a criminal tax lawyer, but rather Hoeness' long-time tax advisor Günter Ache, 65, who has his office in northern Germany. They met in the 1980s while skiing in Switzerland. Ache has an outstanding reputation as a tax consultant, but voluntary declarations are tricky. If it concerns speculation on the stock market, all purchases and sales have to be declared in detail. If an error is made, it dashes all hopes of avoiding a conviction.

Tax Authority Hands Tax Return to Prosecutor

Hoeness' text was rather sloppily written. For a number of years, he netted out his gains and losses from shares and currency dealings, which is not allowed. "A beginner's mistake," says a leading Munich criminal tax lawyer.

Hoeness made losses for two to three years, and calculated this as a negative balance. This is also not allowed. Not surprisingly, the tax authorities found that Hoeness' declaration was insufficient. They transferred the tax dossier to the Munich public prosecutor's office, which by Feb. 1 launched an investigation into Hoeness on suspicion of tax evasion and, in mid-March, searched his villa high above Tegernsee lake, a resort area in the Bavarian Alps. The officials presented a search warrant and a warrant for his arrest. Hoeness paid €5 million in bail, allowing him to continue to enjoy his freedom.

Since then, Hoeness has revised his voluntary declaration, which was said to be plausible, but not sufficiently detailed. Prosecutors are reportedly satisfied with the subsequently submitted version, but this no longer has any influence on the question of immunity from criminal prosecution. The public prosecutors calculated that Hoeness owed back taxes of €3.2 million, which he promptly paid. But now they want to know why a very large amount of money was temporarily deposited in his bank account. During a currency transaction, over €20 million reportedly accumulated in the account. Hoeness has yet to comment on this.

Sources within the judiciary say that investigators took such a hard line because they have a bone to pick with Hoeness. In Sept. 2011, after consuming copious amounts of alcohol, Brazilian player Breno, who was 21 years old at the time and a Bayern Munich defender, set fire to his rented villa in the affluent Munich suburb of Grünwald and was arrested. Hoeness was outraged at this treatment by the authorities and launched into a public tirade: "What the Munich public prosecutor's office is doing is an absolute disaster! Issuing an arrest warrant against a young man who is completely devastated, with the ridiculous justification that he may be suppressing evidence -- he can't speak any German!"

Later, he regretted making this comment. "My biggest mistake was to attack the public prosecutor's office. They didn't appreciate that at all," he said.

Jail Sentence Possible If the public prosecutor and the courts don't accept the late voluntary declaration, Hoeness may well have to go to jail. In 2008, the Federal High Court determined that for alleged tax evasion sums of over €1 million, the courts generally can no longer issue a suspended sentence. Even if Hoeness' lawyers manage to push through as many as deductions possible, they will hardly be able to reduce it below the million-euro threshold.

In addition to possible tax evasion, the charges could also include bribery in business transactions -- if, that is, it doesn't already fall under the statute of limitations. Why did Louis-Dreyfus gave his friend millions to go on a gambling spree? Was it a small inducement to help pave the way for the hoped-for extension of Adidas' endorsement deal with Bayern Munich? The agreement was renewed in September 2001, although Nike would have paid significantly more.

It wouldn't be the first dubious business deal between Adidas and the Bavarians. In the spring of 2001, the record-holding championship team was negotiating the transfer of Peruvian striker Claudio Pizarro from Werder Bremen. Pizarro had scored 19 goals the previous season, so he and his manager were asking for $7 million net income for four years, plus a one-off net payment of $8 million.

Since the Bavarians apparently couldn't or wouldn't pay this much money, Adidas stepped in. Pizarro was given an eight-year advertising contract worth $21.6 million, which was precisely the amount needed to end up with $8 million after deducting all taxes. The deal included a confidential side agreement ("only two originals, no copies"), in which the Bavarians guaranteed the one-off payment stipulated by Pizarro.

'I'm Almost Hopelessly Ambitious'

Why does a club or an individual go to such lengths? One reason is competition, the underlying principle of capitalism. Nowhere is competition as demonstratively practiced as in sports. It's all about performance and rankings -- there are winners and losers, champions and teams that are relegated to lower divisions. The best should win, but in football this dictum is increasingly associated with the pronouncement that, in reality, only the rich can win. Virtually no one has grasped this as clearly as Hoeness, who has transformed Bayern Munich into a stronghold of sports capitalism. He is the ideal man for this kind of system.

Hoeness, whose parents ran a butcher shop in Ulm, in the southern German state of Baden-Württemberg, wanted to move up in life, right from the start. Moving up was all about acquiring money, wealth and a large, successful business -- unlike his father, who never expanded his shop, and closed up the place if five pfennigs were missing from the cash register, and only reopened for business when the money was found. Football was one way of moving up. "I'm incredibly, almost hopelessly ambitious," Hoeness once said of himself.

There were bigger talents in German football in the late 1960s, but none of them were driven by such determination. Hoeness told his father to wake him up every morning at 5:30 a.m., so that he could go jogging before school. Out on the pitch, he rarely picked his brother Dieter to play on his own team because he felt he would jeopardize their chances of winning. Later, Dieter Hoeness went on to become a successful center forward, and spent part of his career at Bayern Munich.

Losing was the worst thing that could happen to Hoeness. He took it as a personal insult. When he was 15, he said to a teammate at TSG Ulm: "Look, the others are off to drink beer, and we'll play for Bayern Munich someday." Three years later, he was in a team with legendary players like Franz Beckenbauer and Gerd Müller. At the age of 20, he helped the team become European champions, at 22 he was on the West German national team that won the World Cup in 1974. He also took home the UEFA Cup Winners' Cup three times.

After the World Cup in 1974, Hoeness sold 300,000 books within just a few months, and personally signed each copy. He offered his wedding to the media -- for 75,000 marks. He posed for a menswear company in hot pants and with a bare torso. He opened up his half of a duplex to a tourist group, pulled on a pair of oven mitts and served them Leberkäse, a Bavarian meat specialty that's similar to boloney. He was a new kind of professional athlete, one who strove to turn every occasion into a money-making opportunity. After friendly matches, coach Dettmar Cramer would often say: "Gentlemen, I leave you in the hands of Uli here, you can settle everything with him!"

General Manager of Bayern at 27

An injury to his right knee put a stop to his meteoric career. At the age of 27, Hoeness became the general manager of Bayern Munich. "I put on a tie, sat down at a desk and after three hours there was nothing more to do," is how Hoeness described his first day at work. At the time, in 1979, Bayern Munich was a different club. It was 7 million marks in debt and the golden days were over, with Beckenbauer in the United States and Müller on his way there.

But Hoeness confided in his pal Paul Breitner that he would turn this scrap heap into "a new Real Madrid."

At best, it became a poor reflection of the elegant Spanish team. For decades, the team's style of play had remained relatively unrefined. Once they scored a goal, they would play a defensive, boring game to hold the score, led by football warriors like Klaus Augenthaler. With obvious delight, Hoeness snatched up the best players from other teams in the Bundesliga. In the early 1990s, when Karlsruher SC valiantly fought their way to the top of the first-division standings, they were practically bought up lock stock and barrel by Bayern Munich. One after the other, Michael Sternkopf, Oliver Kreuzer, Mehmet Scholl and Oliver Kahn transferred to Munich, followed later by Thorsten Fink and Michael Tarnat.

Hoeness struck another blow to his rivals' ability to compete in early December 1999. At the time, he signed a secret agreement with the Kirch media group, which operated TV stations Sat.1 and Premiere, which broadcast Bundesliga games back then. The contract secured the Bavarians the equivalent of some €15 million a year for the first three years. Starting in 2003, this amount was supposed to increase to €40 million. The reason behind the highly confidential agreement was that Bayern Munich had agreed to the central marketing of TV broadcasting rights by the League Commission. Back in the summer of 1999, the Bavarians had still insisted on being able to market their TV broadcasting rights themselves in the hope that this would significantly boost their revenues.

This plan failed due to resistance from other clubs. The Bavarians acted as if they were prepared to make concessions, but then signed the secret contract. Up until 2002, when the Kirch media group went bankrupt, some €20 million were deposited on account 6105308 owned by FC Bayern Sport-Werbe GmbH at the club's principal bank, Hauck & Aufhäuser.

'We Have to Become More Arrogant'

Later, in 2000, Hoeness argued before the League Commission in favor of accepting an offer by Kirch for the awarding of broadcasting rights, although at the time a considerably better offer was made by a rival. An assessment by Lovells law firm on the issue came to the conclusion that the Bavarians under Hoeness had been "bought" by the Kirch group.

His at times contemptible manner of beating the competition was often accompanied by notorious comments such as this: "We're going to slaughter our opponents." No wonder the rest of the country hated Hoeness and Bayern Munich. And Hoeness? He loved it. He said: "We have to become more arrogant." On the side, he set up a sausage making factory.

Success at any price -- that was one side of Hoeness. The other side was that of a patriarch who looked after his people. He made Bayern Munich into a family firm, although the core family still remains the team from the 1970s: Beckenbauer, Rummenigge and Breitner. Hoeness personally oversaw the alcohol detox of Gerd Müller, who found himself stranded in faraway Florida.

It's a two-faced kind of capitalism that reigns in Munich, on the one side brutal and arrogant, on the other dependable and caring. The club doesn't gamble with its funds and it doesn't have debts. In fact, it has €100 million in the bank and a stadium that will soon be paid off. A good 80 percent of FC Bayern belongs to its members, with Adidas and Audi each holding 9 percent. This is a team without a trace of Chelsea's oligarch, of the consortium of sheikhs that rules Paris Saint-Germain and Manchester City, or of Manchester United's US business tycoon.

Hoeness' FC Bayern is in perfect health, and that's one reason it's been able to draw someone like Pep Guardiola, considered the world's best soccer coach since his time with FC Barcelona. Guardiola picked a respectable team run by respectable people -- or at least so he thought when he agreed this winter to join FC Bayern.

Hoeness knew what was coming at that point, yet he continued to play his new role, that of the good, wise man who tells everyone how to live an orderly life and how to do sensible business. A SPIEGEL reporter accompanied Hoeness during those weeks in which he was simultaneously two different people. One side of Hoeness was the respectable soccer team manager and sausage factory owner. The other was the tax evader Hoeness, the man who had already turned himself in, the man who was later arrested and remained at liberty only in exchange for a hefty bail, still having to report twice a week to the police.

And all the time this was going on, Hoeness was hoping the public wouldn't catch wind of any of it, allowing him to maintain his image as a moral authority. Hoeness liked being described as a role model. It's unclear whether he was even fully aware of the double life he was leading, or if at some point he stopped noticing the contradiction between the public figure and the private citizen.

Chatting With Merkel On Jan. 12, a Saturday, Hoeness filed a voluntary disclosure of his tax evasion. Three days later, he took an early morning flight to Berlin to participate in a board meeting of the Germany Integration Foundation, an organization that aims to promote the integration of immigrants. Chancellor Merkel had called him personally beforehand to ask if he would like to be present, and expressed her high regard for Hoeness.

After the meeting, Hoeness sat down for a coffee with Merkel at the Chancellery. It was a pleasant meeting as always with the chancellor, a stimulating talk, Hoeness said the next day, adding that he finds Merkel highly intelligent, with incredibly quick comprehension. He added, "She said to me, Mr. Hoeness, we are going to have to play soccer in Europe now, 90 minutes, perhaps even 120 minutes. But I hope we don't have to go into a penalty shootout, because Bayern isn't very good at that."

Hoeness made these comments about Chancellor Merkel from his office at FC Bayern Munich's headquarters on Säbener Strasse in Munich on Jan. 16, four days after he had filed his voluntary disclosure with the tax authorities. On the desk in front of him lay an invitation from a company asking him to give a talk at a company party. Hoeness picked up the invitation and read aloud, "You have demonstrated that it is important, in addition to taking economic responsibility for employees and clients, never to lose track of social and societal responsibility as well."

Setting the letter back on his desk, Hoeness declared, "That says it all." He has always moved through the world with his eyes and ears open, Hoeness continued, adding that he is someone who "just understands how society works." He said, "People like me, who are fairly independent economically and very successful, increasingly need to assume social responsibility as well. These days no one is going to accept that you earn more money than many others unless you think for others as well."

Hoeness sounded very committed and convincing as his spoke. At the same time, his gaze wandered constantly to his TV. The sound was off, but the screen showed teletext from broadcaster n-tv with the latest stock market indexes.

Eight days after his voluntary disclosure, Hoeness was invited to the Bavarian town of Peissenberg, where the local branch of the CSU was holding its New Year's reception. Local party chair and CSU secretary general Alexander Dobrindt, who had issued the invitations, stood in the foyer, and seemed as excited as a little boy.

'You Have To Be Credible'

Onstage and in the best of moods, Hoeness explained what he felt was going well and what badly in Germany. He spoke confidently, giving the impression of being someone who understands what's going on and whom someone politicians should listen to more often. "These days, whether you're part of a club or part of politics, you have to go your own way, you have to have a clear concept and you have to be credible," Hoeness said.

Yet there were moments of hidden honesty that day as well. In Peissenberg, Hoeness fielded a question about left-wing politicians' plans to increase taxes on wealth and on high incomes by responding, "There are certain limits beyond which citizens are simply no longer willing to keep doing even more for others." It is a mistake, he added, to believe that "if we keep taking more and more from the wealthy, then things will be better for those with less. That's simply not the case. In fact, the opposite is true! If the wealthy eventually have had enough and decide to do less, then those with less will have to start working more again, to be able to maintain the status they currently have."

During the trip to Peissenberg, Hoeness proudly mentioned that his going rate for such talks has reached over €25,000 and that he donates every euro of that to charitable organizations. He expressed his disdain for the center-left Social Democratic Party's candidate for chancellor, Peer Steinbrück, who keeps his honorarium for himself.

Evading Taxes but Donating to Charity

That same evening, Hoeness gave hundreds of insurance agents a talking to. "The way I see the responsibilities of companies and of people is that those who are doing especially well have a damn responsibility to society, a responsibility to give those who aren't doing well a helping hand, in the hope that they will seize that opportunity and soon become full members of society once again," he declared.

That statement sounds as if it stands in direct contradiction to Hoeness' tax evasion -- since the very idea of taxation is that a government uses that revenue to give those who aren't doing well a helping hand -- and yet it isn't a contradiction. In fact, one could say the theoretical figure described in 2009 by philosopher Peter Sloterdijk finds a real-life counterpart in Uli Hoeness.

Central to the philosophy Sloterdijk describes is the idea of government as an enemy of freedom, and freedom as the highest commodity in capitalism. Adherents of this philosophy don't believe they live in a market economy, but rather "in an order of things that must be defined, though with a grain of salt, as semi-Socialism based on a foundation of private property, animated by mass media and drawing on government taxation," Sloterdijk writes. They feel they are at the mercy of a "government kleptocracy," a "monster that keeps taking," and that the most feasible response to this is an "anti-fiscal civil war." Sloterdijk suggests that instead of paying taxes, the wealthy should donate their money to "societally beneficial entities of their choice."

A major topic in a SPIEGEL interview with Hoeness last fall was the ill will he has sometimes caused at the club when he has revealed internal matters in these talks he gives, or when his witty critiques of everything under the sun have overshot their mark. Hoeness explained very earnestly that he has to do these things, because that's what people want to hear, and that if he didn't, companies wouldn't pay so much money for his appearances -- money, he pointed out, that he gives to charitable causes. The world would be a poorer place, in other words, without Hoeness' frivolous comments. He seems to truly believe that by doing the talk circuit and collecting donations for it, he is making the world a better place.

That attitude explains the strange coexistence of evading taxes but donating generously. It's not so much a matter of keeping all the money for oneself, but rather of keeping that money away from a government that can't be fully trusted. Hoeness certainly isn't alone in his skepticism toward the government. No one wants to pour their money into a bureaucracy if they harbor doubts as to whether that bureaucracy will handle the money well. Fortunately, though, not everyone reacts by resorting to illegal methods, as Hoeness has done -- while most likely allaying his conscience with the donations he has made. Those who do good things find it easier to do bad things as well, because they're able to tell themselves that they are essentially good people.

Much the same can be said of people who achieve great things. They sometimes tend to award themselves privileges and allow themselves not always to follow rules and laws. They see this special status as a reward for their great achievements.

A Duopoly in the Bundesliga Perhaps Hoeness takes such a perspective as well. Didn't he lead Bayern back to its spot among the top European teams, all while being good to his German competition? Didn't he give Borussia Dortmund a loan when the club was nearly bankrupt, and grant impoverished FC St. Pauli a benefit match to help that team stay afloat? Yes, he did. But then something unnerving happened to Bayern: In the last two years, Borussia Dortmund won the Bundesliga. Some sport analysts already speculate the team may become the new dominant force in the Bundesliga, the monopolist of success.

Bayern reacted to that news by making a few smart purchases of players and has so far dominated the league in the current season. But it seems that wasn't enough. Hoeness himself also made a few moves that wouldn't be out of character for Gordon Gekko, that ultimate capitalist from the movie "Wall Street."

In mid-April, Hoeness suddenly began an assault on the so-called "Spanish conditions" supposedly threatening the Bundesliga. After Bayern won 4-0 against Nuremberg on the same day that Dortmund beat Greuther Fürth 6-1, FC Bayern president announced he saw "a need to take action" and that "such results aren't acceptable in the long term." He also said had already spoken about the matter with Dortmund's business manager Hans-Joachim Watzke.

The term "Spanish conditions" refers to the way FC Barcelona and Real Madrid have formed essentially a private society for the superrich and super strong, sharing between them around 60 percent of the Primera División's total sales, as well as its titles. This is very different from Germany's Bundesliga, whose trademark is the constant excitement of not knowing who will win, following the motto that anyone can beat anyone -- although that hasn't been strictly true for the last three years. The question, then, is whether Germany is on its way to becoming a Spanish-style duopoly dominated by Dortmund and Bayern Munich.

When Hoeness laid out his idea, Watzke wondered how it would work. Was Hoeness volunteering to donate players -- or even funding -- to struggling members of the competition? The distribution of national television funding for the next four years was decided in November 2012, and Bayern has certainly complained about the ample earnings that go to the Champions League's top teams. Besides, Watzke believes, more equality within the sport would come at the cost of quality, since German teams capable of keeping up with top teams around Europe will have to dominate the national league.

Watzke was thus taken by surprise when he read about his telephone conversation in the newspaper -- Hoeness had gone public with the idea. Was that the Bayern manager's plan all along? Did Hoeness want to garner acclaim for himself as the lone do-gooder, the champion of solidarity within the Bundesliga, the socialist of soccer?

'He Wants to Destroy Us'

Hoeness has since backpedaled on his plan. It turned out to be hypocritical in any case, since Hoeness must have known, even as he was supposedly campaigning for more equality, that his team had plans to snap up Dortmund's wunderkind Mario Götze. That deal went through for €37 million, because that's the price the player -- or more accurately his advisor -- and Dortmund established in a release clause in Götze's contract. And because it's a price FC Bayern was able to pay.

Now Dortmund is spreading rumors that it was not FC Bayern as a club, but rather Hoeness working alone, who leaked news of the transfer to the mass-circulation newspaper Bild, in order to unsettle Dortmund just before the first leg of the team's semi-final match against Real Madrid last week. According to the rumors, Hoeness was desperate to prevent his absolute worst-case scenario, which is that Bayern might lose to Barcelona in the semi-final and that Dortmund win the Champions League. A Borussia official says of Hoeness, "He wants to destroy us." Hoeness, meanwhile, denies he was the leak. All sides here are playing hardball.

Bayern would also dearly love to snatch away Dortmund's striker Robert Lewandowski, doubly weakening its rival team. The competition believes the Bavarian team has long since agreed with Lewandowski on a transfer -- although such an agreement is against regulations -- by the season after next at the latest, at which point the Polish striker will be a free agent. If Lewandowski wants to transfer before that, he will need Dortmund's consent, but the team has no interest in approving an early transfer, not after Götze -- and not even for the €25 million Bayern is said to be willing to pay for Lewandowski.

Modern capitalism, too, began with the trade in human beings, in the form of slavery. Some people may never get used to the idea that athletes have a price tag and can be traded back and forth. But that trade is by no means the specialty of Bayern Munich alone. Bayern buys Götze from Dortmund, Dortmund buys Marco Reus from Mönchengladbach, Mönchengladbach buys Max Kruse from SC Freiburg, and so on. Bayern Munich is such a successful team precisely because it understands this business so well -- thanks to Hoeness.

Not everyone is able to come to terms with this free-market form of soccer. There will always be hardliners in the stadiums who manage to cling to the dream that their sport is first and foremost about heart and soul, about football, about a particular city. When goalkeeper Manuel Neuer transferred to Bayern in 2011 from Schalke 04, the Bundesliga team of the western industrial city of Gelsenkirchen, that went too far for many fans. Neuer was a real Gelsenkirchen boy, who had himself shouted his heart out in the stands, cheering for the home team, before he followed the scent of money and success to Munich. Schalke's hardcore fans were outraged at Neuer's perceived betrayal, while Munich fans reacted with hostility to their team's new purchase. This wasn't the kind of player they wanted.

Now all that is forgotten. Soccer has a great power to reconcile, and the name of that power is success. When Bayern Munich plays as enchantingly well as it has done this season, even diehard Bayern haters find themselves enamored with the team for the beauty of its game, for the joy of a successful combination ending in an exquisite goal, for the intoxication of a match well played. When that happens, no one is thinking about the trade in humans, because consumption always makes it easier to reconcile ourselves with capitalism. Consumption is good at creating illusions. We see the lovely picture on the surface and not the system behind it.

Tepid Support From Bayern Fans

Tax fraud, though, has a way of seriously disrupting that illusion. At Bayern's game against Barcelona last Tuesday, fans showed far less support for Hoeness than expected. One fan held up a small sign that read, "Uli, I'm sticking by you." When, during the halftime break, the stadium's video screen showed a shot of Hoeness cheering for a goal, the audience clapped a bit, but the atmosphere remained strangely cool and no chants rose up in support of Hoeness.

Does this mean that a soccer stadium is a hotbed of government supporters, people who want to make sure their politicians have plenty of money to work with? Hardly. But Germans are touchy when it comes to questions of justice. They have no sympathy for someone who has a lot to begin with, and then commits fraud in order to have even more. Tax fraud is a phenomenon of the wealthy. For someone drawing a normal salary, as the majority of the fans in the stands do, withholding money from the government is never even an option. In that sense, it can seem unfair that some people even have the option of committing fraud, while others don't.

The people who reacted most strongly, though, were seated comfortably in the VIP section, especially Martin Winterkorn, CEO of Volkswagen, and Rupert Stadler, CEO of Volkswagen's subsidiary Audi. Both men sit on Bayern Munich's supervisory board and will have a say in deciding Hoeness' future.

The football manager now finds himself at the mercy of a different aspect of capitalism -- a global company with a built-in obsession with being scrupulously correct to protect its reputation, especially after a major sex and corruption affair tainted the company in 2005. A major corporation such as this one has a particular interest in being clean so that customers don't get angry with it and stop buying its products. An Audi car cannot afford to be connected in any way to the word "fraud," and it is Audi that provides FC Bayern's vehicles.