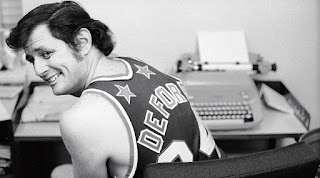

CONFESSIONS OF A SPORTSWRITER - Frank Deford (1938-2017)

For more than five decades, FRANK DEFORD was the peerless bard of sports journalism. In 2010 he turned his gaze upon himself—a self-examination worth revisiting as we remember SI’s greatest storyteller

by FRANK DEFORD, JUNE 5, 2017 / SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

THERE ARE MANY ROLES a man plays in life. Son, Husband, Father, Breadwinner. If he is successful: Star, Boss, Grand Old Man. But nothing, I believe, is quite so thrilling as getting to be The Kid. That is, you, as a novice, are accepted by your elders into their privileged company. You are not quite their peer. You are on trial, tolerated more than embraced, but at least you are allowed to step into the penumbra of the inner circle, to sniff the aroma of wisdom and humor and institutional savoir faire that belongs to those old hands. It’s a heady sensation.

It was at Sports Illustrated that I was, for the one time in my life, The Kid. I had come to the magazine fresh out of Princeton. Understand, in 1962 it was hard for someone like me not to move to the head of the line. Women and minorities were not given such opportunities at that time, so competition was limited to my own kind: the male WASP. On top of that, I was a Depression Baby — and, even better, conceived during a bad dip in the Depression. Except for my dear parents, nobody in America with any sense was having babies around the time I was born, so when I came out of college and dutifully did my six months in the National Guard, there were only a handful of us coming into the job market.

Also, I had Bill Bradley in my hip pocket.

Back then basketball was barely a national sport; the NBA drafted players based on their newspaper clippings. But it happened that when I was a senior, Bradley showed up at Princeton. Freshmen were allowed to play only on freshman teams then, before crowds of parents and girlfriends, so who, outside the basketball curia, knew about Bradley? Well, by dumb luck I did, and so I casually told SI’s basketball editor that, guess what, the best sophomore in the country was at, of all places, Princeton. Naturally, everybody snickered at me as a silly Tiger, but when I told them that Bradley had turned down Duke and I threw in some statistical mumbo jumbo, they got interested. A great basketball player at Princeton? Hey, that could be a classic fish-out-of-water piece. Almost on a lark I was sent out on what would be my first big story.

So, because of yours truly, Sports Illustrated introduced Bill Bradley to the world. And Bradley was even better than I had touted him. Hey, The Kid knew inside stuff. The Kid was obviously a comer.

In those halcyon days there was still a lot of booze in journalism. Writers were understood to be two-fisted drinkers. You wrote a story, you wrote a chapter; then you went out and bellied up to the bar. When I was The Kid, I was regaled with tales of the sportswriter who covered for his tosspot buddy by filing a story for him; the punch line was invariably that the sober writer’s editor called him the next day and asked him why he couldn’t write as well as his rival—when, of course, he had written the rival’s story himself.

Most newspapers had a designated bar where reporters gathered. SI had one too. In fact, when it closed down, one writer, Bud Shrake, was taken off mere sportswriting and given the more important assignment of reconnoitering the neighborhood for the next appointed watering hole.

I was given to understand that, as The Kid, I could go down to the saloon where the managing editor and his apostles drank and take a position on the fringes, listen and learn, dare speak only when spoken to. The youngest writer above me in this coterie, Bill Leggett, was about seven years older than I, but he was so callow compared with the others that he was simply called Young. “Hey, Young.” “What’s up, Young?” And here I was, far younger than Young himself. What were they going to call me: Real Young? Too Young? Instead, it was the only time in my life I was called by my diminutive, Frankie.

The managing editor was a mythic character named Andre Laguerre, who had restructured our magazine, saving it from going out of business after 10 years of steady losses. He had a French father and a British mother, spent his formative years just like me, going to the racetrack and serving as a newspaper copyboy — me in Baltimore, he in San Francisco, where his father was posted for a few years as a consul. Laguerre was a fascinating paradox: He was almost constitutionally withdrawn, but among the friends he chose, he was magnetic. He had not been an especially good writer, distinguishing himself most as a sports columnist in Paris, writing under the rakishly Yank name of Eddie Snow, but he loved good writing and seemed to have had drinks with every famous writer extant. If he ever played a sport, I never heard tell. He smoked cigars and drank Scotch and made the sun move across the heavens.

Laguerre’s mysterious past came out only in dribs and drabs. There was the early upbringing in the U.S., then schooling in Britain. International correspondent. In World War II he was wounded and barely escaped Dunkirk, plucked from the flaming waters of the North Sea. He became Charles de Gaulle’s press secretary. He married a daughter of Russian royalty. One rare moment of revelation came of an evening at the bar when the subject of a recent plane crash arose. To my surprise, Laguerre spoke up: “I was in a plane crash once.”

We all turned to look at him, shocked that he had ventured a personal revelation, never mind that it was so spectacular. “It was from Paris to London,” he said. “We crashed just short of Heathrow.”

But having ventured that far, he merely reached for his glass, leaving us all in suspense. Well, The Kid couldn’t stand it. I asked, “So, sir, what’d you do next?”

He took a swallow, allowing the drama to build, and then said, “Why, I took a cab, Frankie.”

While Andre was a considerable influence on me, I can recall only one occasion when he offered me advice about writing. I imagine he guided me mostly by osmosis. His genius as an editor was that he made you want to please him, but he wanted you to do that by writing in your own distinct way.

The time he gave me advice was when I wondered whether writing about sports was really substantial. Laguerre simply said, “Frankie, it doesn’t matter what you write about. All that matters is how well you write.” I suppose that has helped sustain me all these years.

It also helped that Laguerre featured one long story at the end of every issue. He called it the bonus piece. Till then, the marquee piece of sportswriting had been the newspaper column — just a few hundred words. Styles varied, but for someone like Jimmy Cannon or Jim Murray, the column could consistently be a gem. I always thought that reading Red Smith in the New York Herald Tribune for the first time was like being in Delft around 1660 and stumbling on Vermeers: perfectly framed little portraits with just the right touches of light. But I didn’t aspire to that. It was Laguerre’s bonus pieces that I wanted to write and, after a time, did. I saw my stories less as small, precise Vermeers than as big, fleshy Rubenses.

INSTITUTIONALLY THERE WAS real camaraderie among sportswriters, because more than other journalists we traveled together and then wrote en masse, in the press box. I was hardly surprised that last July, when Mets general manager Omar Minaya attacked New York Daily News beat writer Adam Rubin, all Rubin’s competitors came passionately to his defense. Sportswriters are rivals, but close ones, like chefs who eat in each other’s restaurants.

I came in a bit after airplanes became the accepted mode of long-distance travel, but stories of writers — especially baseball reporters — caravanning on trains with the players they covered were still fresh and legion. The leading men, the columnists, would often drive south together for spring training and then reassemble for the traditional progression of prime events: the Masters (scheduled purposely to catch the writers coming north) and the other major golf tournaments, the Triple Crown races, the U.S. tennis championships at Forest Hills and the Davis Cup, championship fights, the World Series and the most important college bowl game. It was a well-ordered universe, unpolluted by playoffs. Playoffs were hokey, tainted, bush. The NBA, it was harrumphed, “played 72 games to eliminate the Knicks.” In the same way, sportswriters had previously thought night baseball was Satan’s work, and they were chary of anyone, like Bill Veeck, who dared to marry sports with showbiz. That too was bush.

After all, for decades — for half a century! — American sport had been static. There was no real difference between what mattered in 1900 and in 1950. Everything was played in the same place, and there was a distinct pecking order. Baseball ruled supreme, then came boxing, horse racing and college football. Golf, tennis and track popped up periodically. Basketball and ice hockey were pretty much afterthoughts. When the great Paul Gallico was asked, in the late ’30s, why he was giving up sportswriting for the Daily News to write novels in the south of France, he replied, “February.” There was just nothin’ cookin’ from the bowl games on New Year’s Day till the pitchers and catchers reported.

Of course, this would serendipitously lead to the ultimate sports journalism sacrilege, the notorious Swimsuit Issue. To fill the late winter vacuum, SI would invariably run a tropical travel story, usually (and hopelessly) titled fun in the sun. In 1964, Laguerre chose to put fun in the sun on the cover in the person of an attractive young lady standing ankle-deep in water. She was by no means seductive — more preppy — and not at all buxom, in a bathing suit that was more burka than bikini. But sure enough, a few letters of shock and protest came in, one from a librarian declaring that such pornography had no place in her sanctuary. Laguerre, who was invariably bemused by American puritanism, merely mumbled something like, “Wait’ll next year,” and thus from little acorns do big oaks grow. Soon enough, there was Cheryl Tiegs in a fishnet top.

When I would go out on stories, men would invariably ask me — wink, wink — what it was like hanging out with all those beautiful models. Reluctantly, I explained that Cheryl and her ilk didn’t ever grace the office, let alone in fishnets. It was only the photographers, like the suave and handsome Walter Iooss Jr., who got to consort with the models. Immediately upon this revelation, I could see my stature decline in the eye of the beseecher.

Then, in 1989, the 25th anniversary of our sin in the sun, the people in SI’s business department decided to really blow it out. They made a slick video, assembled several of the models and, along with Jule Campbell, the lovely editor who always assembled the issue, took a swimsuit dog ’n’ pony show on the road, to play for advertisers. I was invited to go along as the emcee. We were given the Time Inc. company plane, and away we flew, just us, across America: the likes of Elle Macpherson, Kathy Ireland, Carol Alt and Rachel Hunter, Jule and me.

We bonded, the girls and I. On Valentine’s Day, when we played Detroit (there was automobile advertising then), I wrote out personal Valentines and read them to the girls at the luncheon. But all too soon our road show closed, and I quickly lost touch with my sirens. Except that years later in Italy, on a beautiful soft night, in the outdoor restaurant at Villa d’Este by Lake Como, I looked across the lawn and spied Rachel. She saw me, too. We rose as one, and, eyes only for each other, her long auburn hair glimmering in the starlight, we quickly closed the distance, until at last we stood together again and exchanged a sweet kiss.

She took me over to her table and introduced me to her then husband, Rod Stewart. He did not rise, nor did he express the slightest interest in who I might be or in where his wife and I had once spent a cold and innocent February together. And so I returned to my table, to my patiently waiting wife, never to see Rachel again.

Ah, I thought, but we’ll always have Detroit.

BEFORE SI BECAME a famous girlie magazine, it was new competition for newspapers, and we had a devil of a time even getting admitted to the pews in major league press boxes. Later, radio and TV broadcasters were viewed as even more dangerous aliens. I remember when radio transmission became mobile, giving sportscasters — notably, Howard Cosell — the ability to go where only writers had gone before: into the locker room. The radio boys had to lug huge backpacks. They looked like spacemen. But there they were: equals with us royal writers.

Dick Young of the Daily News was as good a reporter as ever there was in sports. He was prickly, though. I always steered clear of him because I knew he didn’t suffer anybody but the daily press; everybody else was bush. In the locker room, when some poor radio spaceman would stick his microphone in as Young was interviewing a player, Young would spout vulgarities, ruining the poor guy’s tape.

Actually, the whole idea of journalists going into the locker room is an American idiosyncrasy. I can remember being in Barcelona at a Davis Cup match in ’65, when Bud Collins and I waltzed down to the Spanish locker room. We weren’t just barred. The Spanish sentinels looked at us oddly, as if we’d tried to enter the ladies’ room.

I understood. I’ve never felt altogether comfortable in a locker room. I always feared I was intruding on someone else’s privacy. The point was brought home to me when I did a story on the Boston Celtics’ opener the year after John Havlicek retired. He had come to the game as a civilian, and we were standing outside the locker room. As I started to enter, John said, “I’ll see you later. I can’t go in there. I don’t belong there anymore.”

Excuse me: John Havlicek didn’t belong in the Celtics’ locker room, but I did?

Of course, much was made about women entering the locker room when they began to join the profession. But then sportswriting, even more than the rest of journalism, was a man’s world. Locker rooms? Women hadn’t been allowed in press boxes. As late as 1973 my colleague Stephanie Salter was thrown out of the huge annual banquet of the Baseball Writers Association, which was being held in a hotel ballroom.

So I was very fortunate to be covering tennis when Billie Jean King took the bull by the horns. Billie Jean more than anyone else raised my consciousness. Here she was, virtually running a sport, getting up at 6 a.m. after a night match to appear on Sunrise in Cincinnati or some other TV show, serving as a symbol for a whole movement, taking a lot of crap from people who didn’t appreciate her—and winning championships. I knew she would beat Bobby Riggs in their Battle of the Sexes in ’73. Only two or three times in my life have I been dead sure of an outcome in sport, and that time is at the top of the list. Apart from the fact that Billie Jean was simply a better player than Bobby was then, and immune to pressure, she was really a lot like him. They both knew how to work a crowd, only Bobby was in it for the con, Billie Jean for a cause.

AS I WATCHED from the press box, television made athletes into personalities, not just distant performers on the field. TV gave sports what the movies had given actors: close-ups. Slowly, then, athletes became more human and thus potentially more heroic.

By good fortune, I also arrived just as sport was exploding. Come back, Paul Gallico, it’s a new and improved February! The NFL ballooned, pro basketball and hockey weren’t bush anymore, college basketball became truly national, franchises shifted, new leagues were created, free agency blossomed, players went on strike, collegians turned pro, Title IX was enacted, stadiums grew domes, AstroTurf replaced God’s green earth, the Olympics were politicized, agents surfaced, money proliferated, and television brought it all to you live, right there in your family room.

Nevertheless, this was the ante-software era. You still needed paper. When on deadline, you’d contact Western Union and tell them to have someone on duty late. Then, after the game you’d go back to your hotel room and type out your piece. Typewriters were loud, especially when everyone else was trying to sleep. Sometimes the poor people in the next room would bang on my wall, or they’d get the front desk to call me. I’d go into the bathroom and turn on the shower to mask the sound of my typing on the floor. This was not conducive to inspired prose. For a sportswriter, this was the equivalent of working in a foxhole with mortars whizzing overhead.

At last I’d drive to Western Union, hand over the pieces of paper, go back and sleep, then call the office in the morning. One time I was writing about a basketball game somewhere, and when I called in, the editor said, Why didn’t you write about such-and-such a strategy? I knew this editor didn’t know jack about basketball; he’d obviously seen the game on television and was regurgitating what the “analyst” had proclaimed. That’s when the scales fell from my eyes. As a consequence of television, sportswriters had lost their original reason for being, which had been to tell you what happened at a game you didn’t see. I thought: I’m redundant now.

That was in large part why I began to spend a lot of time away from the reach of television and many of the big games, chronicling personalities or athletic exotica, out on the fringes. In a sense I got to go back in time, to see the way it had been before the big money, when sports often meant hustling and scuffling, when there was a vagabond spirit and a quaintness to it all.

I played against the Harlem Globetrotters in Bologna, Italy. This violated my promise never to do with my subjects what they did for a living. Leave that hokiness to local television reporters. I thought I’d learned my lesson when traveling in a reconfigured limousine with a wrestling bear named Victor. This noble ursine treated me with respect until I wrestled him, and he pinned me in about eight seconds.

Thereafter Victor disdained me, cuffing me whenever the spirit moved him. But the Globies kept urging me to suit up as one of their patsies on the New York Nationals. After all, the Nationals were tall and white and limited, a perfect fit for me. Finally I agreed to do it, but only on our last night together. Hey, if they made too big a fool of me, Bologna would be in my rearview mirror the next morning.

As it was, the Globies decided that discretion was the better part of valor in dealing with a guy who would write about them. They treated me with kid gloves, and I went for a huge eight points. Double figures were within my grasp! But then Marques Haynes dribbled out the clock. As I left the court, Jerry Venable approached me. “Next time, Frank,” he said, “it’s your ass.”

“Don’t worry, Jerry,” I assured him. “There won’t be a next time.”

Unlike the Globies, Roller Derby skaters were unaware that you should play up to a writer from a national magazine; rather, they felt no compunction about embarrassing me. One of the most prominent skaters—let’s call him Donnie— was flamboyantly gay, and late one night in Minneapolis, when I was seated with several skaters in a dark hotel bar after a game, he made a move on me. It was duly noted by those in attendance. As the plot would have it, I had already arranged to ride alone with Donnie to Duluth the next day. Also duly noted.

When the game began in the packed Duluth arena, I was seated by myself at the press table. After only a jam or two, the Bay Bombers called timeout and skated over to a position just above me. There, a cappella, led by their fabled captain, Charlie O’Connell, they looked down upon me and sweetly sang, “Here comes the bride.”

I was mortified, but then it dawned on me that none of the baffled Duluth patrons understood what was going on, so I blew kisses to the Bombers, and the game resumed.

It’s ironic, but in a profession in which we necessarily bunch up, I became an oxymoron, the lone-wolf sportswriter. Research a subject, make phone calls, go out somewhere alone, scout about, interview, return to my house, write, turn the story in. Long-term parking, aisle seats, shuttles, rental cars, motels, interstates, cheeseburgers and fries, minibars, Magic Fingers. I wasn’t just writing about Americana. I was Americana. I now own the largest collection of hotel shampoo bottles in the world. (I don’t believe there’s a second largest.)

OF COURSE, IF you have curiosity and the right temperament, being a writer alone on the road is fascinating. In dealing with people as subjects, you must be something of a chameleon, an actor, and I have a touch of that in me. The people you’re writing about don’t know you, so you stress the facets of your personality that most please them. But if there’s one regret I’ve had as a sportswriter, it’s that the major sports are so predominantly male that you don’t get to write about many women. The reasons why that’s unfortunate for a male writer are 1) men aren’t as inclined to open up to men as women are, and 2) except where sex is involved, men and women talk more honestly to one another. There’s an instinctive flirtation built in. Interviewing is really only what you learned to do on a high school date. It’s “What kinda music do you like?” taken to a somewhat higher level.

Then again, the one time I was frightened by a subject, she was a woman—and probably the smallest person I ever interviewed. Robyn Smith, who would later marry Fred Astaire, was the best female jockey at that time, and while doing a piece on her, I discovered a few, let us say, fibs that she had told to make her life more enthralling before she became a jockey. We were sitting alone in a barn when I confronted her with these inconvenient facts. She was holding a rider’s crop, and as I began politely inquiring into these discrepancies, she slapped that whip across her palm—glaring at me all the while. Any moment, I expected to find out what it feels like to be a horse’s withers, but mercifully Robyn allowed me to leave the barn unscathed.

In any event, of all athletes, I’m most intrigued by jockeys and baseball pitchers. Pitchers fascinate me because a live arm is such a capricious possession and a dicey thing to depend on, and jockeys interest me mostly, I suppose, because I’m so tall and they’re such brave little people. I remember being at the Preakness Ball in 1972, standing at a urinal next to Ron Turcotte, who was riding the favorite—the Kentucky Derby winner, Riva Ridge—the next day. He looked up at me and said, “Hey, how ’bout giving me a couple inches off your top, eh?” (Ron was Canadian.)

“If I did,” I said, “you wouldn’t be riding Riva Ridge tomorrow.”

He laughed and nodded ruefully. He didn’t win that Preakness, but he won the Triple Crown the next year on Secretariat. Then, only five years later, he went down in a spill and has been paralyzed, in pain, ever since. I always wondered whether he would’ve liked making that deal with the devil: taking some of my height, never having the glory—never having Secretariat—but always having his legs, having peace.

UNFORTUNATELY, BEING A sportswriter is like being Oscar Wilde’s picture of Dorian Gray. You age as all around you the players stay forever young. You stick around while your contemporaries grow old in sports years and fade away. “I’m sorry, I’d like to be your friend,” Bill Russell told me when he retired, “but friendship takes a lot of effort if it’s going to work, and we’re going off in different directions in our lives.” And so here comes the next cohort, only now they’re not your peers. Your portrait ages some more, and now the coaches are of your vintage. As you grow older, in fact, you gravitate toward stories about coaches, not just because they’re now your new contemporaries but because they’ve lived longer, more complicated, lives. They’re simply better stories. Coaches are plots. Players are snapshots.

Generally speaking, baseball managers and basketball coaches are more interesting than football coaches, who tend to be valued more for their organizational skills than for their personalities. Incredibly, Billy Martin made me his confidant even though I had barely met him. The first game I watched him manage, he got mad at a rookie umpire named Rich Garcia (who would go on to become tops in his profession), and when I went into Martin’s office before the game the next day, he greeted me with, “Whaddya think o’ this? I go out to give the lineup card, I call that Garcia a spic.”

“I don’t know, Billy,” I said tentatively.

“Why not? They called me a dago. Let’s see what the sonovabitch is made of.” I don’t know how much I influenced Martin, but he decided not to slur Garcia. I guess Billy’s whole life was premised on finding out what the sonovabitch is made of—starting with himself.

Bear Bryant was the coach who got me into the most trouble, if inadvertently. He was going for the record for most victories by a college football coach. He was old, the Bear; he’d be dead in little more than a year. He was tired, and he didn’t mind admitting to me that his assistants were doing most of the real coaching. He also had to pee all the time. Now, this is hardly a stop-the-presses revelation among old men. But when, in my article, I mentioned it (and just in passing), the entire state of Alabama came down on me. Petitions were mailed in demanding that I be fired. Worse, when another SI writer, John Papanek, went down to cover the game in which Bryant set the record, the good citizens in the Heart of Dixie cursed him and one actually spit on him.

The Bear himself thought the whole thing was a tempest in a teapot. And the truth was, he had to pee all the time, and he didn’t make any bones about it. But as Paul Harvey would’ve intoned, there was the rest of the story too. Coaches, like sportswriters, are a tight fraternity. They always call each other Coach, as if it were a military rank or religious office. A few months after Alabama threw its hissy fit, I called up North Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith and said I’d like to do a story on him. I’d known him for almost 20 years, and we’d always enjoyed cordial relations.

“I’m sorry, Frank, but I won’t talk to you,” he said.

Flabbergasted, I asked, “Why?”

“I didn’t like the way you treated Coach Bryant.”

Regardless, I knew Dean did not easily give himself away. Even if he had talked to me, he wouldn’t have revealed the Real Dean Smith. Other subjects are quite the opposite. Indiana coach Bobby Knight despised SI because he felt, not without cause, that he had been portrayed harshly in the magazine. When I gingerly approached him—writing a letter first—he took his time getting back to me and then took more time before he finally agreed to cooperate. But once he did, he was remarkably obliging and forthcoming. The first day I was with him we stayed up till 2 a.m. discussing the Civil War, about which he knew a great deal more than I did. Don’t forget, it’s two people on a high school date, and it’s not just the reporter who’s doing the flirting.

So, anyway, I told Dean—excuse me, Coach Smith—that I was sorry, I understood his position, but I had a job to do, and I was going to write the story anyway. And he replied, simply, that he understood my job. I was welcomed into his office every day I was at Chapel Hill; we would exchange pleasantries, and then I would interview his assistants, his players, even his good friend the university chancellor. What a weird experience. I’ve seen Dean occasionally in the years since, and our relationship is exactly as it was before. It’s as if that episode never happened.

But the trip to Alabama also brought me the most bizarre good fortune of my professional life. The morning I returned home from seeing the Bear, I boarded a plane in Birmingham bound for Atlanta. The plane had previously stopped in Jackson, Miss. On the seat next to mine someone had left that morning’s edition of The Jackson Clarion-Ledger. Idly, I picked it up. There was a long story on the sports page—exactly, I’m afraid, the kind of feature that has since disappeared from sports pages.

I read the piece. It was by a fine writer named Rick Cleveland, about a football coach named Bob (Bull) Sullivan. Bull—or Cyclone, as he was also known—had coached only at a little junior college, but he had become something of a legend in the oral sports history of Mississippi. He had been dead for several years, and this was the only article of any substance that had ever been written about him.

The Toughest Coach There Ever Was was the expanded version of Cleveland’s story of Bull Sullivan that I wrote for SI. Bull was as fascinating a figure as I ever heard tell of. The article made him famous. I went to Jackson a year later when, because of that piece, Bull was put in the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame. Today I still get the cover of the magazine mailed to me to autograph. It struck a chord. Bull was the archetype of the coach for whom men of a certain age had once played. In a way he was a purer Bear Bryant, because he had never been anything but a coach, never been sidetracked by fame and glory. Bull’s widow believed that I was some kind of divine messenger who had appeared to give her husband the acclaim he’d never had in life. I agree with her premise, but I think that the divine messenger was that unknown passenger who left the copy of the Clarion-Ledger on the seat next to mine. I just dug into a story that had been dropped into my lap.

SPORTSWRITING WAS STILL something of a netherworld when I chanced upon it. I got in just before the sun came up. To be sure, there had long been respectable parishes. In many towns the sports editor-columnist was a revered figure, the de facto head of the Chamber of Commerce for sports. Grantland Rice, a hero of the First World War, was for decades a sort of national grandfather figure, the patron saint of American fun and games.

On the other hand there were a lot of hacks in the field, their copy peppered with clichés and strange synonyms that no one employed in normal conversation. Tilts. Frames. Speed merchants. Educated toes. Worse, in some cities scribes were on the take. If you, say, had a rasslin’ bill or a donkey baseball game coming to town, you were expected to grease palms in the sports department in order to get some ink. When I first got into the profession, a promoter or public-relations man might offer to provide me the town’s finest allpro distaff companionship in my motel room.

Years later, I remember standing at the bar with Pat Putnam, the much-respected boxing writer for SI. All of a sudden Pat started talking, in a melancholy way, about covering boxing for The Miami Herald years before. A big bout was coming to town, and the promoter approached him about ladling out more ink about what a fabulous card it was surely going to be.

“I was dead broke, Frank. We owed a lot of bills. I can’t tell you how tempting it was.”

It was obvious Pat wanted to ask me what happened, so I did. “Well, did you take it?”

“No, I didn’t.”

So, yes, even among sportswriters, virtue could be its own reward, and, yes, we are a more honorable craft now. There are more good sportswriters than ever, although there may not be more good sportswriting. In the hallowed past we were more engaged in trying to reveal human nature, but now, because all the games are on TV or online, there is a natural disposition to endlessly analyze, dissect and predict, to enlarge minutiae. No wonder a whole profession didn’t detect steroids; we were too busy studying the animal entrails of drafts.

There’s always talk about the so-called Golden Age of Sports, but I’m convinced that the Golden Age of Writing About Sports began just about the time that I, The Kid, providentially strode into the vestibule.

I was a character in the age’s last scene, too. The NBA didn’t have a full-season network contract then, in the ’60s, but on Sunday day games in the Finals, a network showed up, cherry-picking on the cheap. When the Celtics won another championship, a young assistant rushed onto the court and asked Red Auerbach to come right up to the TV booth. Red looked down at the boy. “Where the f--- were you in February?” he asked, waving him off with his cigar. Then, gloriously, he threw the other arm round me and said, “I’m going with my writers.”

It was the last hurrah for the press. After that, it became the media.

Commenti

Posta un commento