Connie Hawkins: The Hawk Ages Gracefully, 1991

Posted by bobkuska - October 12, 2023

[This is a nice article about Connie Hawkins as a 48-year-old NBA retiree living in his beloved adopted city of Pittsburgh. What’s doubly nice is the story’s told by Jim O’Brien, best remembered today for his 1970s ABA column in The Sporting News. As O’Brien gladly would have told you, he was a proud native Pittsburgher through and through and had known and admired Hawkins for decades from seeing him around town. The two were almost the same age, and, when he writes of Hawkins, O’Brien is writing about a friend—and vice versa. In fact, The Hawk once passed along the following note of mutual admiration: “To Jimmy O’Brien & Family. From one super player to one super writer equals two great persons. Peace & Love, Connie Hawkins #42.”

In his retirement, The Hawk had taken up tennis. “I would classify myself as a moderate weekend hacker who can possibly lose to anyone at any given time,” he mused back in the 1980s. By the 1990s, his forehand had come up a notch, but Hawkins remained the same easy-going, easy-to-be-around guy whose company O’Brien enjoyed. O’Brien’s check in on the former number 42 appeared in the March 1991 issue of Basketball Digest.]

****

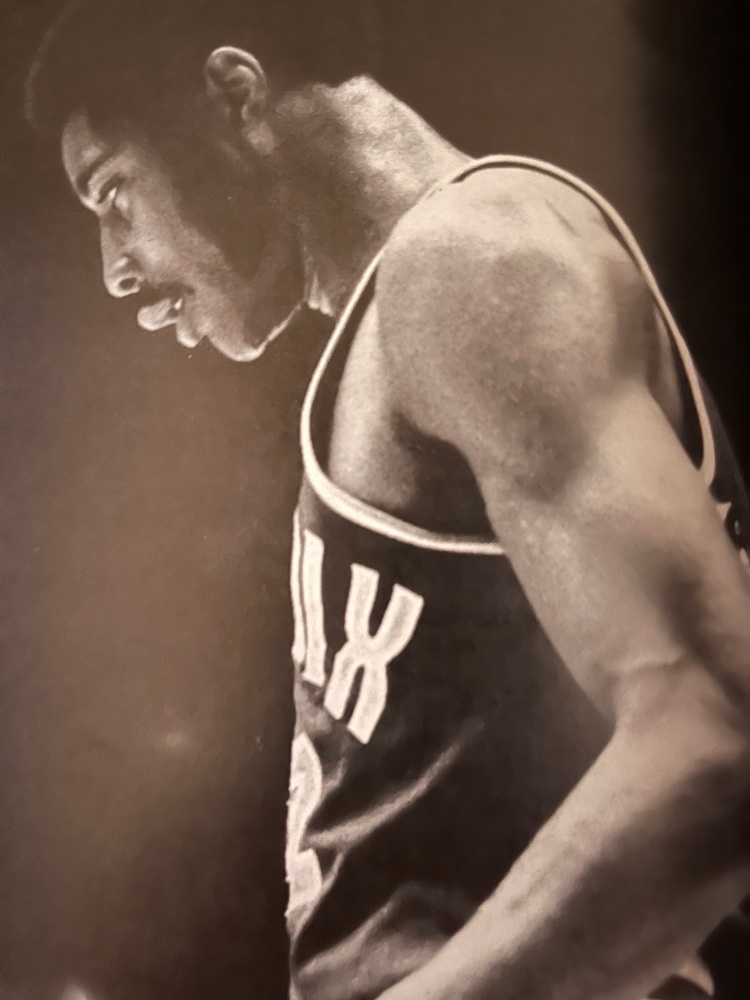

Connie Hawkins could hear the good-natured teasing in the background as he sat in a booth at the Edgewood Tennis & Fitness Club, just east of Pittsburgh, and he smiled that toothy smile of his that would be familiar to those fans who followed his New York schoolboy or American Basketball Association and NBA days. Hawkins still holds Phoenix Suns playoff scoring records, and he remains a legendary figure on the playgrounds of Harlem and Brooklyn.

He played pro ball in three different leagues for teams in Pittsburgh, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Atlanta, and toured the world with the Harlem Globetrotters. Those who witnessed the wondrous things he did with the basketball in his enormous hands still tell tales about his magic.

There remain too many who never saw him play, however. Two waitresses and two other workers who were putting up photos of former and present Pirates and Steelers in a sports-bar restaurant in the club had just picked out a framed poster of Michael Jordan of the Chicago Bulls. “Here’s a real basketball player,” hollered one worker, hoping Hawkins would hear him. “How come we can’t find any photos of Hawkins here? Didn’t he used to play basketball, too?”

Hawkins had to laugh; it’s the story of his life. Later, one of the fellows in the restaurant stopped by the booth where Hawkins was holding court and said: “Why don’t you bring us a photo of yourself so we can hang it up? I hear you were a pretty good basketball player in your day.”

Pretty good? Neither the waitresses nor their fellow workers had ever seen Hawkins play basketball, they admitted, but indeed they knew he was pretty good. Enough people they knew had said so. How good? Well, Hawkins was doing some of the same things Michael Jordan was doing on the basketball court before Jordan was born.

“The Hawk” was one of the first high flyers in the world of professional basketball. When Jordan was young, he idolized Julius Erving. When Erving was young, he idolized Hawkins. That’s how Erving came to be known as Dr. J—because of the high-flying flair with which he operated on the court. “I was Dr. J before Dr. J was Dr. J,” Hawkins is fond of saying.

Hawkins was a hero, a schoolyard legend, to a lot of young athletes in his native Brooklyn. He was wrongly implicated in a basketball-related gambling scandal when he was a freshman at the University of Iowa in 1960, banned from NCAA and NBA play for a long period, and forced to perform on the fringe for too many years.

He played for the Pittsburgh Rens in the American Basketball League, then the Harlem Globetrotters, then the Pittsburgh Pipers and Minnesota Pipers in the American Basketball Association before he successfully sued the NBA and gained the right to play in that league.

“If he hadn’t gotten such a bad deal [an eight-year NBA ban],” says former Boston Celtics star and Hall-of-Famer Bill Russell, “you would mention Hawkins with Elgin Baylor and Bob Pettit.” Baylor and Petit were two of the best basketball players of all time, and both are in the Hall of Fame.

****

The Phoenix Suns won a coin flip with the Seattle SuperSonics for the right to sign Hawkins for the 1969-70 season, the franchise’s second year in the NBA. Hawkins promptly carried the Suns to their first playoff berth, leading the team in scoring (24.6 ppg average) and achieving First Team All-Star status. He played in the All-Star Game each of his four full seasons with the Suns and was voted the team’s MVP by Phoenix fans after the 1970-71 season. Hawkins averaged 20.6 points a game during his career with the Suns, and he also ranks among the team’s all-time rebounding leaders.

At 6-feet-8 and 215 pounds, he wore his No. 42 with great pride and gave the Suns almost instant credibility because not too many expansion franchises—except for the Milwaukee Bucks with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar—ever had players of his superstar caliber.

Hawkins had won All-City and All-America honors as a high school ballplayer in Brooklyn, but he was forced to play in basketball’s underground after he was bounced out of Iowa for the crime of accepting a $10 or $20 bill here and there (a total of $200) from a former NBA player named Jack Molinas, who had been kicked out of the league years before for gambling. Molinas would hang around schoolyard basketball games in the New York area and give some of the kids cash from time to time, so they’d have some spending money. It cost Hawkins and a few of his friends dearly.

At 19, Hawkins won the MVP award in the ABL. At 26, he was the MVP in the ABA. Both times he led pro teams in Pittsburgh to championships and averaged between 27 and 28 points per game.

At 48, The Hawk can still fly, but he prefers to lay low and stay close to his nest in the Pittsburgh suburbs. On this particular day, he wore a glistening light blue warm-up jacket. He looked bright-eyed and positively glowed when he talked about his current life and reflected on his basketball-playing days. The Edgewood Tennis & Fitness Club—where Hawkins likes to play tennis and talk to friends over snacks and raspberry-apple juice—and the Forest Apartments that overlook the club and include a two-bedroom unit that Hawkins calls home are both owned by Eugene Litman, a local entrepreneur.

Litman is a part-owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates and once had a similar stake (though at cheaper rates) in the Pittsburgh Rens. His brothers Archie and Lenny have long looked after Hawkins on and off the basketball court, while Litman’s brother, David, and wife, Roz, have looked after Hawkins in and out of the courtroom. The latter Litmans argued Hawkins’ case versus the NBA.

David Stern, now the NBA commissioner, represented the league as an attorney back then. ”I never saw lawyers who were as genuinely concerned about the best interests of their client like the Litmans,” recalls Stern.

Asked why he chose to live almost all of his adult life in Pittsburgh, Hawkins had this to say: “About three years ago, Pittsburgh was rated ‘the most-livable city in America’ by some people [Rand McNally]. I knew that long ago. I’ve been around the world with the Harlem Globetrotters, but there’s no place like Pittsburgh. I liked New York, and I loved Phoenix—the fans were so great to me there—but it’s cheaper and easier to live in Pittsburgh, and everybody has always treated me so nice.

“I’m happy here. All my friends like it here.

When my brothers came here,

they never wanted to go back to Brooklyn.”

The Hawk always has moved to the beat of his own drummer—a slow, funereal beat. He only played one year of pro ball in Los Angeles with the Lakers after the Suns sent him there in a trade eight games into the 1973-74 season, but he always has been “California laid-back” in his lifestyle.

He has all the money he needs, thanks to his NBA retirement checks, plus a stipend he has received over 20-year period as the settlement for the money and proper acknowledgment he missed during his eight years banned from the NBA. So, Hawkins doesn’t have a job. But he helps out a few days a week at a sporting goods store owned by his longtime friend, Kenny Durrett, a former NBA player who can appreciate Hawkins’ fate of never really getting to play at his best in the NBA.

During his all-star days at Pittsburgh’s Schenley High School, Durrett used to go one-on-one in the gym with his idol, Hawkins, who then was playing pro ball in Pittsburgh. Durrett, a 6-feet-7 forward, was a two-time All American at LaSalle and signed a five-year, million-dollar contract—when that was big dough for a professional athlete—to play for coach Bob Cousy and the Cincinnati Royals in 1971. However, Durrett suffered a knee injury in the senior season, and like his buddy Hawkins, never was able to play in his prime in the NBA.

Hawkins is separated from his wife, Nancy, but they have three children: Shawna, 25, Keenan, 21, and David, 18. David shares Hawkins’ apartment and attends nearby Woodland Hills High School. “I make sure he’s up in the morning, and I make him breakfast,” says Hawkins. “I help him with his homework at night.”

If this is so, it represents a real turn around in the life of Connie Hawkins. As a ballplayer, he had a reputation for sleeping late—trainers used to come, wake him up, and take him to practice—and as a student, he was thought to be illiterate.

“That’s just not so,” says Hawkins. “I was a poor student, for sure, but I can read. Because of my own poor work in school, I see to it that my son doesn’t suffer in the same way. People are always surprised to find me so articulate—like the people from ESPN who did an interview with me—but I can talk and read.”

And he plays basketball once in a while, fooling around against the best young talent in town, which competes in the Connie Hawkins Summer Basketball League. He also loves to play in those legends classics at the NBA All-Star Weekend, as he has done on several occasions. But whether he’s working at Durrett’s sporting goods store or playing tennis, Hawkins still doesn’t push himself too hard. He always has held to an old-fashioned premise that you are to play games for fun. There isn’t—and never has been—an ambitious bone in his body. But there isn’t a mean bone in his body either.

“He’s always been like a brother to me,” says Durrett, 41, standing tall behind the counter of his Pro Shoes store in the East Liberty section of Pittsburgh. “When he first came here to play in Pittsburgh with the Rens, I was trying to learn how to play ball in junior high. I was horrible. He took me aside and showed me some things. I figured if he could take time out of his valuable schedule to show me some things, then I should work harder. And I did. My team won the state championship when I was a senior in high school. I always wanted to be like Hawk was.

“I could talk forever about what a great person he is. And if things hadn’t happened to him that prevented him from playing college and pro basketball with the best, he’d have been doing the sort of things Michael Jordan is doing now.”

Durrett and another former NBA star forward from the Pittsburgh area, Billy Knight, of nearby Braddock and the University of Pittsburgh, often play tennis with Hawkins at the Edgewood Tennis & Fitness Center. Jack Merchant, a self-proclaimed “old pro” at the club, calls Hawkins his friend.

“If he had played tennis as a kid, he could have been a good tennis player,” says Merchant. “[Tennis pros] Tony Trabert and Marty Riessen, for instance, both were outstanding basketball players as well as tennis players in their younger days. The moves are rather similar in both games.

“Connie covers the court so well, and he’s a very stylish player. He doesn’t fool around in tennis. He tries to play the game the way it should be played. He keeps the ball going all day. He can play hard—if he’s pushed. We’ve given up trying to finesse Connie at the net. He’ll just nail the ball if you try to get too cute.

One of Hawkins’ few ambitions is to win a 45-and-over championship in tennis and become a rated player. “Guys in that category,” says Merchant, “have all the smarts. They’ve lost a lot of their stuff, but they sure play smart. They’ll spot a weakness and exploit it.

“Connie is a Gold Card Member here, so he can come in and play whenever he wants. He’s nice enough to play with anybody. He’ll play with the worst player in the world, or he’ll play with the best. He’s fun to play with. He’s just a hell of a nice guy on the court and off the court.”

Sounds like the scouting reports on Hawkins have remained the same.

Commenti

Posta un commento