‘People Going Home Tonight’

by Barry Ryan

The Ascent: Sean Kellty, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling's Golden Generation

Gill Books

Carrera signed Eddy Schepers ahead of 1986 season expressly to serve as Roche’s wingman in the mountains, but unlike Valcke, his new leader’s long absences from racing were no grounds for an existential crisis. At 31 years of age and after almost a decade in the peloton, the Belgian had seen everything and was fazed by nothing. As an amateur, he was gifted enough to win the Tour de l’Avenir and the Giro delle Regioni. As a professional, he was canny enough to understand he was never going to be a champion, and he carved out a niche instead as a deluxe domestique, flitting between teams in Belgium and Italy according to demand for his services. Schepers was a hired hand, and he simply got on with the job in 1986, helping Visentini to win the Giro and Urs Zimmermann to 3rd place at the Tour. ‘It was a good season, even allowing for Stephen’s injury,’ Schepers says.

Off the bike, Schepers and Roche struck up a solid rapport. Roche spoke little Italian, and so it was a relief to be able to converse in French with Schepers, who could in turn step in as a translator if required. As Roche’s roommate, Schepers found himself acting as a part-time sports psychologist in that trying first year, geeing his leader up or dispensing frank Flemish home truths as the occasion required. When they reunited at the start of 1987, however, he saw a man and a rider transfigured. ‘We were always roommate at races and training camps, and I’d see that he was always heading off to extra work in the afternoons,’ Schepers recalls. ‘When I’d ride behind him in training, it was like riding behind a motorbike.’

Schepers was by Roche’s side throughout the spring, but he was informed by Boifava that he would not be required at the Giro. The team’s rationale, that he should spare himself to help Roche at the Tour, was sound, but it jarred with the harsh economic reality of a man on Schepers’s modest salary. ‘I needed to make money and at that time, the prize money was better at the Giro than at the Tour, especially if you were riding for a good team with a rider who could win overall,’ Schepers says. He explained his predicament to Roche, who in turn went to bat on Schepers’s – and his own – behalf to Boifava. ‘I needed to have someone like Eddy who was the same size as me, and ideal for bike exchanges,’ Roche says. ‘He had good tactical sense, he was someone I could count on, and we spoke the same language as well.’

Boifava conceded the point. Roche struck a blow for his own status, and won Schepers’s undying loyalty in the process. Schepers proceeded to demonstrate his commitment to Roche’s cause on the mountaintop finish at Terminillo, when he found himself in a two-man escape with Jean-Claude Bagot and bartered away stage victory in exchange for help from his Fagor team later in the race – the very same Fagor team that had already begun tentative transfer talks with Roche. ‘I was the only one with Stephen, but I couldn’t ride for him on the flat if he needed me in mountains too, so we chose a bit of a collaboration with the Fagor team there,’ Schepers says. ‘They did some work for us after that.’

At that point, Roche was in the maglia rosa, but after Visentini whisked it off him at San Marino, his claim on team leadership, and by extension Giro victory, seemed over. In Roche’s oft-repeated telling of the 1987 Giro, Schepers played a significant part in convincing him otherwise in their hotel room that night by encouraging him to attack Visentini, even if the Belgian demurs on that point. According to Roche, the pair sat on their beds watching a television interview in which Visentini flatly dismissed the prospect of riding the Tour in his service, and decided there and then to flick through the Garibaldi, as the Giro roadbook is named, and pick out the most opportune place to ambush their teammate, settling on the medium mountain stage to Sappada two days later. ‘That night we were upset because everyone was congratulating Visentini and nobody commiserated with me,’ Roche says. ‘Visentini was over with the journalists saying, “Roche will ride for me at the Giro but I’m not going to the Tour, I’m going to the beach.”’

Visentini, unsurprisingly, disputes the claim. ‘No, that’s bollocks, complete and utter bollocks,’ he says. ‘I was always very professional and I was going to go to the Tour to prepare for the World Championships and the races at the end of the season. That was the way the team had planned it. The Giro d’Italia was for me and he was going to lead at the Tour de France. That was the plan.’

Roche, however, had never signed up to that agreement in the first place. Long before the Giro began, and regardless of any implied internal hierarchy, he was plotting his ways to win the race for himself. The San Marino setback only served to strip away any pretence of a tacit qui pro quo with Visentini. ‘We didn’t know the exact moment but we knew something was going to happen,’ Valcke says. ‘We knew that at the first opportunity, something would happen.’

The moment arrived two days after the San Marino time trial, over the top of the Forcella di Monte Rest in the Carnic Prealps. As the name suggests, the mountains on the border between Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia regions are not the most demanding, but the gravel-strewn strada regionale 355 that winds across the mountainside is among the most sinuous in the area. Bagot and Ennio Salvador, neither of whom posed the remotest threat on general classification, led the race over the summit, when Roche took it upon himself to shoot after them shortly after the road began to drop, ostensibly in the name of protecting his team’s interests. ‘I couldn’t really attack but if a group got away and I happened to be in it, Roberto couldn’t really ride and I’d be seen to be defending the jersey,’ Roche says, not that anyone was fooled into thinking he was killing Visentini with kindness alone.

One reckless descent later, Roche was 1:30 clear of a peloton that had scarcely computed what was happening. ‘Stephen hadn’t talked about it the night before. Nobody knew he was going to do that, not even me. It was just the situation of the race. He took the decision off the cuff,’ says Schepers. ‘He didn’t come as the first leader, but he poked out an opportunity to put the team in a really good position.’

At first, Visentini didn’t even notice that Roche had scrambled down the descent alone and out of sight. ‘I didn’t realise he’d attacked at all. We were on the descent and riders were taking a drink or eating a panino and so on, when this group slips away,’ Visentini says. ‘I didn’t even realise Roche was in it. We let the group go and they built up a lead of four or five minutes. And that’s how it all happened.’

Not quite. There were still 80 kilometres and two climbs to come before the finish at Sappada, and on the long, flat approach to the next ascent, the Sella Valcalda, Roche’s lead shrank. It is easy to forget, but Carrera were not the only team in the race. Panasonic’s Robert Millar and Erik Breukink were in contention for podium places, as was Tony Rominger of Supermercati Brianzoli, but before either of those teams could set about shutting down Roche’s move, the white-and-blue jerseys of Carrera massed on the front. ‘It was up to the otherteams to chase, but the management reminded us that Visentini was the leader and told us to ride behind Stephen, though I wouldn’t ride on the front of the peloton,’ says Schepers.

As Carrera began to chase, Quintarelli pulled up alongside Roche in the second team car at the head of the race. Boifava was in the number one vehicle, stationed behind Visentini and the pink jersey group, but he had relayed strict instructions to Quintarelli via radio. ‘We told Roche to stay with the break without collaborating. And if it stayed away, so be it,’ Boifava says. ‘That’s normal.’

‘I was in the car with Quintarelli, because he had Stephen’s bik,’ Valcke says. ‘When Quintarelli drove up alongside Stephen, he said to him in Italian, “Hey, Boifava says that you have to stop riding.”’.

Moments later, Valcke rolled down his windows and chipped in with some additional counsel of his own: ‘I said, “Steve, if you have the balls, today is the day to show them.” Quintarelli didn’t speak French and he only realised that I’d given the exact opposite instruction when suddenly he sees Stephen riding flat out on the front, straight after we’d spoken. He kept riding flat out, flat out, and Quintarelli was shouting to Boifava, “Patrick’s just told Stephen to keep riding!”’

Back in the main peloton, Visentini was growing increasingly flustered, driven to distraction by what he felt to be Boifava’s procrastination. ‘Boifava should have sent the team to the front to ride full gas and chase him down, but that didn’t happen,’ he says now. Boifava reckons Visentini should never have allowed himself to fall into the situation to begin with. ‘He made a mistake by sitting in the middle of the gruppo coming up to such a dangerous descent,’ Boifava says. ‘And the thing is, he was actually very good on descents. A leader can’t let a group like that go away. And if he wanted Roche to help him, he should have been up there with him.’

Although the Carrera contingent eventually brought the bunch back to within sight of Roche and Salvador – Bagot had punctured – at the base of the Valcalda, most of them were dropped as soon as the road climbed and a Jean-François Bernard-powered counter-attack bridged across to the leaders. Visentini just about remained in touch on the Valcalda, and even clawed his way back up to the now-expanded Roche group ahead of the final haul towards Sappada. Physically, he still seemed capable of offering resistance, but his mental resilience had been stretched to breaking point, which seems to have been Roche’s objective in the first place. ‘He was very uptight and we knew if we could make him panic and blow his brains, that would be a good scenario, you know,’ says Roche. Yet even at a remove of 30 years, Roche still refuses to admit that his actions consitued outright treason. ‘There was no intention to attack him,’ he says, not entirely convincingly.

The Cima Sappada’s final ramps were its steepest, but a breathless day of racing took its tool even before the gradient kicked in, and Visentini quickly started to slip backwards as the leading group fragmented. The only Carrera rider who could offer any support by this juncture was Schepers, but he hesitated when Boifava ordered him to go to the Italian’s aid. A professional to the very marrow of his being, Schepers had the sangfroid to sense an opportunity. As the 1987 Giro’s most tumultuous stage reverberated around him, he blocked out the white noise and began negotiating his contract for 1988.

‘I was up with Stephen at that stage, and I said to him, “Look, I don’t have much of choice here, I’m going to have to sit up and wait for Visentini unless… Well, if I help you, I’ll need to be certain that we’ll be riding together next season,”’ Schepers says. ‘And Stephen said, “Listen, Eddy. Stay here.” So I stayed with him, and that’s where our friendship became even closer.’

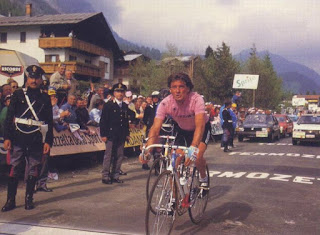

Already guttering, Visentini’s hopes were snuffed out altogether once he was left to his own devices, and he slowed almost to a standstill as Roche and the Giro rode away from him. The finish came after a short, shallow descent, where Johan van der Velde won the stage, and though Roche flagged in the finale, he stayed in the leading group. Immediately after the finish, he held a brief, anxious huddle with Schepers and Valcke in a tent where journalists were watching the race on television before being ushered towards the podium. He had done just enough to take the pink jersey, five seconds ahead of Rominger.

Visentini’s strength, meanwhile, deserted him completely on the stiffest section of the final climb, and he reach the finish almost seven minutes down. Roche was already being helped into the maglia rosa as Visentini crossed the line and wheeled deliberately to a halt in the middle of a scrum of reporters and photographers. On stepping from his bike, he cast his eyes towards the podium with murderous, doomed rage writ across his gace. ‘I want to come up,’ he called out, pointing to his own pink jersey, before RAI television’s Giorgio Martino thrust a microphone in his direction.

‘It looks like you’ve got something to say,’ Martino began.

‘I’ve got lot of things to say,’ Visentini said darkly.

‘Let’s start saying them then,’ Martino responded.

‘Niente. I’ll tell you tomorrow, maybe it’s better,’ Visentini said. ‘But there’s going to be people going home tonight.’

Commenti

Posta un commento