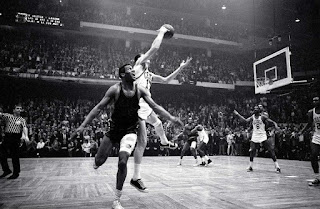

JOHN HAVLICEK - Poetry in Motion

"Trying to guard Havlicek was like “trying to hold mercury in your hand.”

- Former New York Knick—and U.S. senator—Bill Bradley

POINT AFTER / Remembering John Havlicek: a tireless champion who never stopped running

by Charles P. Pierce

Sports Illustrated, May 6, 2019 - Volume 130, Number 10

TO TELL you the truth, I never really saw the resemblance, so I never really got the nickname. When John Havlicek arrived in Boston in 1962, it was said that he’d picked up the nickname Hondo because he looked so much like John Wayne. To my eyes he looked as much like John Wayne as he did Geraldine Page, Wayne’s costar in the forgettable 1953 Western of the same name. Havlicek had the height, but he was broad-faced, jug-eared, and buzz-cut. As his remarkable 16-year career in the NBA went along, and he grew his hair out, he never looked like John Wayne. He looked like a mill hand’s smart son or a farmer’s talented nephew. He never looked like a cowboy movie hero. He just played like one.

Havlicek died on April 25 at the age of 79. It was Parkinson’s disease that he battled, an irony that is cruel in so many ways. Parkinson’s is a progressive disorder of the central nervous system. Its initial symptoms often are involuntary tremors and twitching. Gradually, it deprives the patient of any ability to move voluntarily, and John Havlicek’s greatest gift was that he never stopped moving. Every movement he made on the court was purposeful. He was a perpetual-motion machine, moving, cutting and always finding the open space from which to score. The numbers are impressive enough— eight championships and 13 All-Star teams; leading scorer in the history of the Boston Celtics, which is not the same as the history of, say, the Sacramento Kings; 26,395 points and 1,270 games in which he never seemed to tire. He spanned the lifetime of the Celtics’ greatest dynasty. He came in as a rookie in 1962 and played a year with Bob Cousy. He retired two years too early to play with Larry Bird. In between, he won two titles with a delightfully funky crew that included Dave Cowens and Paul Silas, Jo Jo White and Don Chaney.

He also played on some of the worst Celtics teams ever, including his last one, which won 32 games and probably was lucky to have won that many. It was a ragbag of malcontents and enthusiasts of recreational drugs. The ownership was a mess; the NBA allowed the owners of Buffalo and Boston to “swap” franchises so that the Braves could move to San Diego. That left the Celtics to be owned by one John Y. Brown, and the less said about him, the better. But through it all, Havlicek never stopped moving, never stopped running. In one of his memoirs, former New York Knick—and U.S. senator—Bill Bradley said trying to guard Havlicek was like “trying to hold mercury in your hand.”

The people who knew him well—his teammates and some of the corporal’s guard of reporters who followed the NBA back when it was hostage in its arenas to the Ice Capades and not an international entertainment-industrial complex—remember a genuinely humble and fastidious man. Bob Ryan of The Boston Globe, who knew him best, remembers him as a guy who hung his socks on hangers and arranged his cologne bottles in order of height, and whose locker generally would have passed muster with the toughest gunny at Parris Island.

For those of us who watched him only as a fan, we marveled as everyone did at the way he illustrated at all times that hoariest of basketball clichés: “moving without the ball.” When I was young, my father was an administrator in what was then called an “inner-city” high school. Every now and again, he would open the gym to the neighborhood kids and I would run with them. Inevitably, someone would call me “Havlicek,” and I felt as though I should live up to the moniker. I almost killed myself in those games just so I wouldn’t cheat his name.

The myth was that Havlicek had a third lung, but the truth was that his lungs were so big that technicians needed two plates to give him a chest X-ray. Remember after Secretariat died, and they discovered that his heart was twice the size of the average heart of a racehorse? Same thing. Thoroughbreds are different from you and me.

Commenti

Posta un commento