Paul Kimmage: 'The game is up for the kind of journalism that I practice'

Kimmage is the focus of a new documentary

that tracks his ongoing fight against doping in cycling.

Image: Billy Stickland/INPHO

The Irish journalist is the subject of a new documentary about his troubled relationship with the sport of cycling.

Jul 27th 2014, 10:00 AM 38,771 Views

NEAR THE BEGINNING of the excellent new film Rough Rider — a documentary about former Irish cyclist and whistleblower Paul Kimmage — the 52-year-old sports journalist says: “Libels are the Oscars of our trade — unless you’re getting them, you’re not doing your job right.”

It’s a wry remark, but its inferences undoubtedly ring true. Since of the publication of Rough Ride — Kimmage’s seminal exposé on the widespread use of performance-enhancing drugs in cycling — back in 1990, he quickly established himself as a journalist of considerable repute, mainly owing to the fearlessness that frequently characterised his work.

Yet nowadays, Kimmage finds himself feeling increasingly pessimistic when it comes to his current trade. He no longer feels he would have licence to produce the type of controversial journalism that was highly influential in exposing Lance Armstrong among others — the industry has simply gotten too cautious, he believes.

“I don’t think it would be possible now,” he tells TheScore.ie. “A big part of me thinks the game is up for journalism and certainly I think the game is up for the kind of journalism that I practice. I am pretty sure that will never happen again, which is very discouraging.

“There were difficulties in even getting this documentary made. All it takes is a still of me with a furrowed brow looking at a race and there’s a lawyer jumping up and down somewhere saying ‘oh my god, that’s a sign that he says this guy is doping’. What chance do you have when that happens? It’s very difficult. But the boys have got it across the line, and when people see it, they’ll see the essential truth in it and I’m thankful for that.”

It’s not as if Kimmage enjoys courting controversy, of course. The countless years of vilification, lost friendships and UCI lawsuits have taken their toll. In Rough Rider, his brother Kevin says that he has long since lost the “vibrant sense of humour” that was evident in younger days. Kimmage agrees that his relentless crusade against doping has “changed” him irrevocably as a person.

“I heard what Kevin said and I’m going to take that on board and there would be definitely a lot of truth in that. It has definitely changed me. What changed me was having set out to do what I thought was a good thing for the sport, the way that was received and the way it was treated. It made me very bitter about a lot of people with central roles in the sport at that time. So as much as I’d like to think it didn’t change me, there’s no doubt that it did.”

He adds: “I’m not a complete miserable b***ard all of the time and I would hope I’m a decent father, a good husband, a good son and strive to be all of those things. But it is difficult. You become obsessed by it and I’d agree that it isn’t always healthy.”

During this protracted affair, Kimmage was made to suffer both in physical and practical terms. In addition to the constant stress he endured owing largely to the lawsuits he received, which threatened to ruin him, he also believes he was made redundant from his previous job at The Sunday Times as a result of these problems.

“Did I reach a breaking point? There were times when it was harder than others. Maybe after I was let go by The Sunday Times for a period then it got particularly difficult, but I’ve come through it okay and I feel good about it now.”

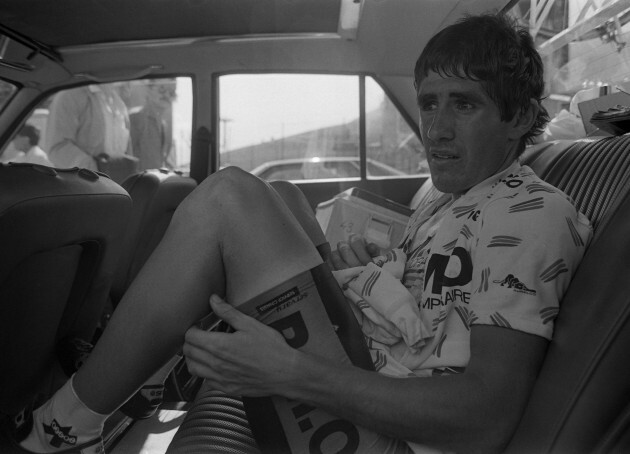

Source: Billy Stickland/INPHO

(Paul Kimmage pictured after a mountain stage of the 1986 Tour de France)

And so to paraphrase a question Kimmage himself once asked when interviewing Eamon Dunphy, what does he see when he looks in the mirror?

“I see a lot of wrinkles. I see a lot of stress sometimes. Watching the documentary was a larger mirror for me, and some of the footage — the shot of me in 1986 when I’m interviewed just after finishing the Tour de France is kind of shocking, because I see someone with a joy and a love for what he’s doing and when I look at that person now, I sometimes see a lot of stress and a lot of strain, although I’m still extremely happy with who I am.

“But there’s no getting away with it, we get old. That certainly changes the way you look in the mirror, but looking at the clip in that documentary, it was quite shocking to me, I thought ‘Jesus, what happened!’

“The other shock was quite early when the boys came to see me. I’d just been served with the UCI writ and I’d lost my job with The Sunday Times, and there was a lot of pressure on us. And I can see the pressure on my face in those interviews, and that’s a mirror of that time and that was pretty tough. But I’m certainly in a much better frame of mind now than I was two or three years ago.”

This talk of pressure and mental strain is not surprising. Kimmage’s combative brand of journalism has earned him as many enemies as it has admirers. Amid the publication of Rough Ride, he was effectively rendered an outcast in the cycling community, most of whom unwisely chose to ignore its underlying messages about the harm that doping was doing to the sport.

Source: AP/Press Association Images

(Disgraced US cyclist Lance Armstrong finally admitted to using

performance-enhancing drugs in an interview with Oprah Winfrey last year)

These early warnings, of course, culminated in the admission of cycling’s biggest star, Lance Armstrong, that he consistently used performance-enhancing drugs during his seven Tour de France triumphs.

And while Kimmage’s relationship with Armstrong is an important part of the story, it is one that features only sporadically in the film, which pleases the Dublin-born journalist.

“This has never been about any individual and it has never been about Lance Armstrong. I started this 10 years before Armstrong won his first tour. It wasn’t about him then and it’s not about him now.

“It’s very convenient for a lot of people in the sport to present Armstrong as the start of the doping problems in cycling and the time it got really bad and to announce him now as ‘the end’ and suggest he’s been banned in this new clean era. But that isn’t the case.

“Was he different to the other dopers and cheats? Absolutely. He was more ruthless and more devious. But that was the only difference. He did not invent doping and it will not end with him.”

Yet despite the disgraced US cyclist’s continual lying and cheating, some have been quick to forgive Armstrong owing to the supposedly genuine remorse he’s shown since.

So can Kimmage understand, for instance, why former US Postal Service team masseur Emma O’Reilly forgave Armstrong after he called her an ‘alcoholic’ and a ‘prostitute’?

“I don’t understand that at all,” he says. “It’s incomprehensible to me that a man who called her what he did and treated her the way he did could be forgiven. But that’s her prerogative. It wouldn’t be me. I’m firmly of the belief that we could all have been buried by this story and it wouldn’t have caused him a thought and his only regret is that he was caught.”

Source: Michel Spingler

Source: Michel Spingler(Former US Postal Service team masseur Emma O’Reilly is one of those who says she forgives Lance Armstrong)

Is there therefore any circumstance under which he could forgive Armstrong for his behaviour?

“I’m not in the same position as Emma O’Reilly is in for a start. I was a journalist doing my job and it wasn’t ever personal for me, so it’s slightly different in that way. I’m not sure the aspect of forgiveness applies to me.

“But I sent him a message on Twitter saying ‘if you want to do something for cycling, go and talk to the independent commission and tell them what you know’. And he can still do cycling a service. I believe he has gone and seen them now. He’s done a lot of damage to the sport, but that’s the one service he could do and I hope he’s done that now.”

Even now, Kimmage has hardly mellowed with age, and he continues to have a troubled relationship with the cycling world, even earning a reputation as ‘difficult’ among some sports journalists, partially as a result of his willingness to criticise them publicly.

Moreover, the list of individuals that Kimmage has fallen out with over the years includes people who he counted as close friends at one point — the former Tour de France-winning cyclist Stephen Roche and the journalist David Walsh, both of whom feature as interviewees in Rough Rider, are among them.

“I grew up with Stephen and I had a personal and intimate relationship with him. So that makes him different to Armstrong as regards forgiveness. A lot would have to happen [for us to be back on speaking terms]. I don’t see any chance of it happening now, even for the mere fact that for the decade that Armstrong was cheating and the decade that I was getting abuse for that, Stephen Roche was in the Armstrong corner applauding it every time.”

Source: Lorraine O'Sullivan/INPHO

Source: Lorraine O'Sullivan/INPHO(Having once been close friends, Kimmage and former Tour de France-winning cyclist Stephen Roche are now no longer on speaking terms)

And while his falling out with Stephen Roche was, in many ways, inevitable, the same cannot be said as regards fellow whistleblower and sports writer David Walsh, who Kimmage has taken “inspiration from since the day I started journalism”.

GAVIN COONEY

REPORTS FROM QATAR

Get Gavin's exclusive writing and analysis from the 2022 Fifa World CupBecome a Member

“I haven’t spoken to David since the Tour de France last year. I met him the same day that I met [my wife] Anne in 1982 and I’d say we’ve spoken on average five times a week every year until last year’s Tour and we haven’t spoken since. I hope that can and will change. But at the moment, we have some difficulties and it’s not great.”

So with these failing friendships in mind, does he have many regrets from down through the years?

“There are a lot of things I’d change, but with regards cycling? No. There are elements that you might change and stuff you wished you’d done better, but overall, no. Writing Rough Ride is the most important thing I ever did. The most important contribution I’ve ever made to my sport. I absolutely could not and would not wish to change that, and that will always be the bottom line.

“I wouldn’t even change [taking performance-enhancing drugs], because that was an experience and it helped me to understand the power of the drug and it helped me to understand the temptation and the pressure to dope.

“While it might have been more convenient not to, as it gave a lot of my detractors some ammunition, I definitely wouldn’t change it. It was part of the experience that formed me and enabled me to write the book that I wrote. I think the book would not have been as powerful had I not taken those amphetamines on three occasions.”

Source: Galit Rodan

Source: Galit Rodan(Former US cyclist Jonathan Vaughters is one of the documentary’s contributors)

At one point during the film, Jonathan Vaughters suggests that many cyclists genuinely believe that keeping quiet about drugs is the right thing to do. Does Kimmage agree?

“I don’t think they genuinely believe that. I think they’re coached and coerced into thinking that, because it’s always been the culture. Keep your mouth shut and just get on with what you’re doing.

“If you remove [the troublemakers] from the sport and set a new tone and a new culture for all the young riders coming through, and you tell them that part of your job as a bike rider is to talk about doping at every opportunity to every journalist you meet… You need to actually encourage your riders into promoting clean cycling and talking about the doping culture and that’s a much more healthy attitude to have than the one that currently prevails, which is omertà [silence] and ‘don’t say anything about it’.”

“There are signs in this year’s race that are very encouraging, and there are other signs that are equally discouraging. What I find extremely discouraging is that you’ve still got the most successful riders in the race associated with people who should have no hand, act or part in the sport.

“Once you see these people continue to have a central interest in the sport and in the tour, then it is very hard to be confident that the culture is going to change. Because these are the people who set the culture in the sport — the directors and the team owners, the people that are relied on to operate a system of zero tolerance for all of the riders they employ and I don’t see that.”

Source: Wildfire Films/Vimeo

And if these supposedly harmful influences are eventually thrown out of the sport, would that be enough to restore his faith in cycling?

“That’s a starting point, but you’ve also got to analyse the performances. What I find encouraging about this year’s race is if you look at the difference between the riders, you take the leader out of it and you’re talking about a handful of minutes separating the top 10.

“Some of them are going backwards yesterday and they’re going forward today. It’s a fantastic battle, so there isn’t that big a difference between the contenders in the race, other than Nibali, who just seems to be on a completely different level to everybody else. I would like to believe it’s possible for a rider to be that superior, but I have severe reservations, because anytime we’ve seen that in the past, it’s been because of doping.”

Yet despite all Kimmage’s underlying pessimism and frequent feelings of disillusionment with the sport, he still somehow manages to retain a child-like passion for cycling at the best of times. Hence, it is no surprise to hear he plans on returning to the Tour de France next year.

“I deliberately took this year off and having stepped back from it, I still found myself in front of the television every day watching it. So that doesn’t seem to work for me — I’ve got to go back to it and I hope to go back to it next year and hope to continue that fight. It’s not something I can let go of now. What’s that saying? ‘I’ve started so I’ll finish.’”

You can watch ‘Rough Rider’ in full on RTÉ One tomorrow night

Commenti

Posta un commento