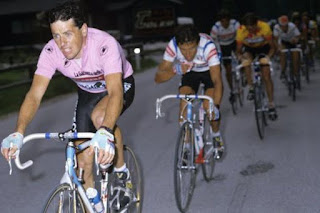

Giro '87: The Sappada Affair

http://www.podiumcafe.com/2011/6/6/2209374/Stephen-Roche

The stats tell you that the 1987 Giro d'Italia was as a pretty dull affair. Three men wore the maglia rosa during the race, two from one team. It sounds processional, boring and dull. But the 1987 Corsa Rosa was a little gem. Grand Tours in which internecine squabbling tears a team apart and yet that team still comes out with one of their riders on top are things of beauty.

Look at almost any Italian Tour de France squad that featured both Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali when the two were at the height of their powers.

Look at the 1962 Vuelta a España when Jacques Anquetil was put to the sword by his own team-mate, Rudi Altig.

Look at the 1962 Giro d'Italia, Nino Defilippis versus Franco Balmamion and the Carpano team being torn apart from within.

Look at the 1986 Tour de France when La Vie Claire's Bernard Hinault messed with his team-mate Greg LeMond's head.

Or look even at the 2009 Tour when Lance Armstrong and Alberto Contador tore Astana apart with their petty squabbling.

Look at the 1962 Vuelta a España when Jacques Anquetil was put to the sword by his own team-mate, Rudi Altig.

Look at the 1962 Giro d'Italia, Nino Defilippis versus Franco Balmamion and the Carpano team being torn apart from within.

Look at the 1986 Tour de France when La Vie Claire's Bernard Hinault messed with his team-mate Greg LeMond's head.

Or look even at the 2009 Tour when Lance Armstrong and Alberto Contador tore Astana apart with their petty squabbling.

The 1987 Giro - the seventieth since La Gazzetta dello Sport first thought aping Henri Desgrange's Tour de France would be a good way to boost circulation - started its 3,915 kilometre journey around Italy in Sanremo before trundling south down the coast and across the Apennines to Bari on Italy's Adriatic coast. It then turned north, back up the coast before swinging west across the Dolomites and the Alps for a finish in the gambling resort of St Vincent. A couple of mountain finishes in the first week would allow the GC contenders to test one and other, but the real fun was set between two scheduled rest days: an uphill time trial to San Marino followed by a transition stage before three saw-toothed days in the Dolomites which would take in ten major climbs. There then followed four days in which the race would alternate between sprinting and climbing before a time trial finale. Three, maybe four, key stages would decide the race. The team time trial, the individual contre la montre at San Marino, and the Dolomites would be at the heart of the 1987 Giro d'Italia.

Twenty teams took the start line in Sanremo. Thirteen of them were Italian. The rest came from France (two), Spain (two), the Netherlands (two) and Belgium (one). But - even allowing for superior weight of numbers and the wonders Francesco Conconi and his colleagues at the University of Ferrara were doing with Italy's top class athletes - 1987 was not a good year for Italian cyclists at the Corsa Rosa. Only two Italian riders made it into the final top ten. Neither of them were rated among the pre-race favourites.

Those pre-race favourites? A poll of the twenty directeurs sportifs came up with eight riders. Getting just one vote each were Gianbattista Baronchelli (Del Tongo), Jean-Francois Bernard (Toshiba), Claudio Corti (Supermercati), Robert Millar (Panasonic) and Roberto Visentini (Carrera). Two directeurs sportifs plumped for Moreno Argentin (Gewiss). Three gave Giuseppe Saronni (Del Tongo) their vote. Eight thought Stephen Roche (Carrera) the man most likely to succeed.

What does that really tell you? That at least thirteen teams didn't even rate their own chances of overall victory and would have to find other ways to make their three weeks trundling around Italy profitable. Add this to the mix: of the 180 starters, 133 made it to the finish, with only four of those eight pre-race favourites among them. Only two of those pre-race favourites even made the top ten. Though at least those two did finish on the top two steps of the podium, suggesting that maybe nine directeurs sportifs actually knew what they were talking about with their pre-race predictions.

One question before turning to the race: how come Carrera had no designated leader, how come they had two pre-race favourites? The direttore sportivo, Davide Boifava, had wanted one leader. And the man he wanted to be that leader - Roberto Visentini - agreed with him. If Stephen Roche rode for Visentini in the Giro, Boifava promised the Irishman, the favour would be returned at the Tour and their roles reversed. But Roche doubted Visentini's commitment to the Tour. Roche in his autobiography:

"My response at the time was that I was hoping to win the Giro d'Italia and that the leadership of the Carrera team would be decided by the strongest legs."

* * * * *

So how then did the 1987 Giro d'Italia unfold? Well it went sort of like this ...

The opening few days of the race saw the peloton tackle the prologue time trial, followed the next day by two split stages: an ultra-short road stage followed by another time trial, down the Poggio. Then came a proper road stage before the stage three team time trial.

The opening prologue saw Carrera snatch the first maglia rosa with Roberto Visentini winning from Steve Bauer. Pink at the end of the last Giro, pink at the start of this, the tifosi dreamt their dreams for Visentini. Visentini's team-mate cum co-leader cum rival, Stephen Roche, scraped home just inside the top ten, five seconds down. The next morning, on the first of the day's two stages, Visentini surrendered the pink jersey to Panasonic's Erick Breukink. Then, in the afternoon, as the peloton time trialed down the Poggio, Roche got the upper hand, taking the stage, coming within fourteen seconds of the maglia rosa and becoming the highest-placed Carrera rider on GC.

Roche, who had been critical of the notion of a downhill time trial ("Three riders have been killed this year, it seems like they are looking for a fourth.") quickly put that behind him and dreamt of the pink jersey:

"If I had not had trouble in the prologue I would be the race leader now. As soon as the chance arises, I hope to take the pink jersey. I took care on the descent and put my effort into the last four kilometres which were flat."

The stage two road race the next day brought no changes and then came the team time trial. Only one team - Del Tongo - finished within a minute of Carrera, such was their mastery of the discipline. Roche was in the pink and fifteen seconds behind him was Visentini. Thirty-seven seconds further back in third was another Carrera rider, Davide Cassani. That's 328 kilometres down, only another 3,587 to go. Already Carrera seemed to have the race stitched up.

Let's fast-forward through the next 1,827 kilometres like this: Carrera rode for Roche, the Irishman retained the race lead and extended the gap to Visentini by seventeen seconds. But Visentini chipped away at Roche and, going into the morning of the stage thirteen San Marino time trial, Roche's lead over him was just twenty-five seconds.

Time to hit the pause button.

Carrera might have defended Roche's maglia rosa so far, but the Dubliner was not happy. He suspected that the team was really behind Visentini, who had won the race the previous year. How justified those feelings were is open to question.

"In the early part of the Giro, [Carrera] helped me pretty well. But there were indications that they would have preferred to be riding for Visentini. I cannot explain why this is so. When I spoke with them they did not have many good things to say about Visentini. He did not treat them very well. In the restaurant he did not behave properly and he was not the kind of fellow that could be relied on for help. Earlier in the year he did not produce anything and they were openly critical of him."

For the most part, Roche thought it was a case of Italians together and screw the rest:

"As a leader I like to mix with all the riders and I did get on fairly well with people. But, behind your back, Italians were Italians."

This lack of loyalty niggled Roche. He felt he had earned - well, bought - the loyalty of his team-mates:

"During the year I had been good to the riders, never taking my share of the prize money. Believing that I would get it back with their loyalty later in the year."

But money don't buy you love and, to an extent, Roche had been riding on his reputation since his stunning early season success in 1981, when he won Paris-Nice as a neo-pro.

1982 had been a lost season for Roche, injury holding him back. In 1983 he had a season that would have been respectable for any third year pro, but disappointing for a rider who had shone so bright so early: victory at the Tour de Romandie and the Étoile des Espoirs and a bronze medal at the Worlds. Then came the acrimonious split from Peugeot - in a case that dragged on and on Peugeot pursued him through the courts for breach of contract, eventually earning a settlement that would see Roche ride with Peugeot's name on his shorts - and two seasons of the sort of forward momentum you would expect of a rider his age but not his reputation: victory again in Romandie in 1984, followed by wins at the Critérium International and the Tour du Midi Pyrénées in 1985, alongside a stage win and podium finish at that year's the Tour de France.

Then came the Winter of 1985. Roche was riding on the track over the winter - the money was good - but a crash at the Paris Six at Bercy in November left him with an injured left knee. At the time, Roche shrugged the accident off, but over the Winter and into the 1986 season his knee kept giving him problems. His time at La Redoute had drawn to a close - the team folded - and he was now riding for Carrera. By the end of March Carrera, unhappy with the return on their investment, sent the Irishman to a specialist who diagnosed that an operation was the only option. Roche disagreed but Carrera insisted. Early in April he went under the knife. Three weeks later Carrera had him riding the Tour de Romandie.

"There were times when I wanted to disagree with what Carrera were proposing but I was in a difficult position. They were paying me a big salary and for what? I was not even riding. But their anxiety to get me back racing was not a help. Before the Tour of Romandie I was twenty days off the bike and there was no evidence my knee was any better. As happened earlier, my return to competition was premature."

Despite his knee causing him pain by the end of the race in Romandie, Carrera threw Roche into the 1986 Giro:

"I nursed the knee all the way through the Giro, getting physiotherapy and injections every day. Two days from the end I could go no further and pulled out."

Then came the Tour. From the start, the knee was troubling Roche, but the pain killers helped him hide the hurt. At the Nantes time trial, he finished third behind Hinault and LeMond, and was up to second overall, just sixty-five seconds off the maillot jaune. In the next two stages, as the race hit the mountains, Roche lost the thick end of fifty minutes.

When others were riding the lucrative post-Tour critérium circuit, Roche was resting and getting his problem diagnosed. Arthritis in the knee joints was the diagnosis. Or was it a cartilage problem? Whichever, in October, Roche went under the knife for a second time.

For 1986, Carrera had got more media coverage from Roche's knee than they got from his performances on the bike. All of this led to a build up of tension within the team. Guido Bontempi and Davide Cassani were just two of his team-mates who had problems with Roche. And then there was the Swiss rider, Urs Zimmerman:

"Zimmerman [...] resented that I was being so well paid when, although he was producing very good performances, he was still earning far less."

Things came to a head between the 1986 Giro and the Tour, when at the dinner table one night Zimmerman started complaining that his wins were paying Roche's salary:

"This was the usual kind of bullshit and there were always a few Italians to agree with him. That evening I was tired of it and, in front of everybody, I asked Zimmerman his name. He could not understand the reason for the question and said I knew his name. Raising my voice I pointed out that I was Stephen Roche and over my professional career had won between thirty and thirty-five races, and that, apart from the Tour of Switzerland, he had not won a damn thing. I was getting paid for what I had won in the past, not for what I should win. I deserved what I received. And I reminded him that he was getting paid for what he won in the past and that he should count himself lucky to be getting what he was."

Roche had been just as snotty with Cassani a few weeks earlier, when there had been a debate about how some of the team's prize money should be shared out and, like Visentini, Roche agreed to leave his share in the pot:

"Cassani straight away remarked, 'You don't need it, Steve, you're getting 250,000 lire a month.' Angry but not prepared to let it show, I replied, 'And, Davide, that does not include what Carrera give me under the counter.' At least it silenced him but I found remarks like that very unpleasant."

Roche's relationship with Carrera was souring. It all looked so familiar. Money had soured his relationship with Peugeot and now money was souring his relationship with Carrera. Would he ever settle down and find a stable team? Didn't he realise that cycling was a team sport and good teams take time to build? Was it only the money that interested him, or was he afraid of his career not lasting long enough, and so grabbed for as much as could as soon as he could? What the bloody hell was wrong with Stephen Roche?

After his second round of surgery, Roche was called to a meeting with Carrera top-brass. General manager Franco Belleri. Direttore sportivo Davide Boifava. And the sponsor himself, Tito Tacchella. They asked him to accept a cut in his salary. He'd given them diddley-squat in 1986. After arguing with Zimmerman that he was worth what he was being paid based on past performance, Roche now wanted Carrera to stand by him for what he'd give them in the future. In the end a compromise was reached: the situation would be reviewed come May.

Then Roche finally started to deliver for Carrera. At the end of February, he won the pre-season Tour of Valencia. In March he came within a gnat's whisker of winning Paris-Nicefollowed by second to Sean Kelly at the Critérium International. In April there was that Liège-Bastogne-Liège. And then, in the pre-Giro leg-loosener, the Tour de Romandie, Roche rode to a decisive victory, and became the first rider to care enough about the race to win it three times. He looked like he'd put his injury woes behind him. But how many times has that been said of riders coming back from the surgeon's knife?

* * * * *

To say that there was - and continues to be - bad blood between Stephen Roche and Roberto Visentini would to be understate the bleeding obvious. But that bad blood didn't start at the 1987 Giro. It started before then. It started from the beginning of Roche's time with Carrera. Simply put, Roche didn't like the guy.

"The only things I heard about him was that he was rich and did not have to ride a bike for a living. His father was supposed to have a big undertaking business in Brescia and Roberto, it was said, was Daddy's boy. He also had a reputation for being a bit of playboy."

Roche thought Visentini hadn't earned respect. Worse, he thought that Visentini wasn't a team player. In his autobiography, Roche singles out several incidents to show how poor a tem player Visentini was. One is from the 1986 Giro, the team time trial. Three klicks into the ride, with Visentini driving the pace, Carrera lost their first rider. They shed more riders until only four remained: Visentini, Roche, Schepers and Cassani. And the time for the team would be that of the fourth rider to cross the line. The stage finished on a climb and Visentini rode twenty metres in front of the other three, pushing the pace harder than his team-mates could cope with. That day Carrera finished second to Del Tongo. Visentini blamed his team-mates. Roche blamed Visentini.

Even in winning the 1986 Giro, Visentini had disrespected his team-mates, Roche felt. He walked out of the post-race team party, preferring to return to his native Brescia where local fans had painted the roads to celebrate his victory.

Even when Visentini did play the team role, Roche was unhappy. Here he is talking about his victory at the Tour de Romandie, shortly before the 1987 Giro:

"On the last day [Visentini] rode up alongside me and said he was available to help me defend the leader's jersey. I think it was the first time I saw him in the race. After Romandie came the Giro and there was no plus side to how I felt about Visentini. Any chance that he had to help me, he did not take. He was foolish because he was doing nothing to earn that help. If the roles were reversed I would have done anything to mark up points with a person whose help I wanted in a future race. But Visentini was not like that. I went to the Giro feeling that he deserved nothing from me."

That's Roche's take on Visentini. Probably best taken with a pinch or two of salt. Cyclists have selective memories sometimes.

What was Roche's position with his direttore sportivo, Davide Boifava, like at this stage? Roche had by now a ... well if not a reputation, then certainly a habit of acting like he knew more that his manager did, no matter how much more experience that manager had. At Peugeot, he had not really got on well with Maurice de Muer or Roland Berland. At La Redoute he was reunited with de Muer and thought Bernard Thévenet to be weak and didn't have a clue. And by May 1987 - the final half of his second year with Carrera, contracts coming up for renegotiation and attempts on-going to rewrite his existing contract, he seemed to be having problems with Boifava. Problems which went back to the Spring Classics and the day Roche tossed away victory in la doyenne, Liège-Bastogne-Liège. Roche privately blamed Boifava for causing him to lose that race.

How much respect did Boifava actually deserve? Well, he was himself was a former pro, riding during Eddy Merck's reign of terror in the early seventies. He'd won a couple of Giro stages, even worn the maglia rosa. He'd been the Italian pursuit champion a couple of times. Just the sort of rider who might make a good DS.

In 1981, as direttore sportivo with Inoxpran, he guided Giovanni Battaglin to success in the Vuelta a España and then, forty-eight days later, in a Giro d'Italia that looked like it had been tailor-made for Francesco Moser and Giuseppe Saronni, Battaglin won again. Go check the record books yourself to see how many people have done that double.

And then Boifava was teamed up with Roberto Visentini. In 1983 Visentini - a former junior World Champion (1975), best young rider at his first Giro (1978), seven days in pink in the 1980 Giro - rode the Giro faster than Saronni. But Beppe had the bonifications that made the difference between being a winner and a loser.

In 1984, it wasn't just Laurent Fignon who was denied a chance to stick time into Francesco Moser when the Giro's direttore corsa, Vincenzo Torriani, cancelled the climb of the Stelvio. Visentini was within spitting distance of victory too. After Torriani pulled the Stelvio, Visentini pulled out. But not before blowing a fuse in a live TV interview. The next year wasn't much better. While second behind Bernard Hinault in the Giro, Visentini had a mental collapse, lost a bundle of time and again pulled out of the race. That was the type of guy he was.

He could climb and time trial and looked the part. And Visentini might have been great too if he hadn't been such a fragile character. He didn't like criticism and he really didn't like losing. He won over fans but not his fellow riders. Angelo Zomegnan, then with the Gazzetta dello Sport, described him thus:

"Roberto Visentini is a modern guy, into good motorbikes and fast cars. Cycling is not the only thing in his life. He likes to ski. He can live without the bike. It is, for him, a sort of hobby."

1986 could have been a really bad year for Carrera. Roche was failing to deliver. Visentini added to the team's heartache by breaking his wrist in Spring. But he recovered in time to ride and win the Giro, a Giro which should be remembered as much for the death of Emilio Ravasio as for the victory of Visentini. That Visentini survived such an emotionally fraught race surprised some. Maybe he wasn't as mentally fragile as people thought.

* * * * *

Looked at like that, the Carrera riders had reason to doubt Roche's ability to survive a three-week stage race without breaking down physically. But they also had reason to doubt Visentini's ability to survive a three-week stage race without breaking down emotionally. Who do you think they should have thrown their weight behind?

The Carrera riders - all of them - were supposed to throw their weight behind whichever of their riders wore the maglia rosa, whoever he was. Let the road decide. But while Boifava might have thought he was running a two leaders, one race strategy, Roche had different ideas. He was running a two teams one race strategy.

Carerra's Giro team was made up of Roche and Visentini along with Guido Bontempi, Davide Cassani, Claudio Chiappucci, Massimo Ghirotto, Bruno Leali, Francesco Rossignoli and Eddy Schepers. Apart from Roche and Schepers, they were all Italians. Out of them all, there was only one rider Roche felt he could count on: Schepers. The Belgian gregario had stood by Roche the year before when others criticised the amount he was earning. When, at the end of 1986, Visentini wanted Carrera to drop Schepers - he had shown more loyalty to Roche during the Giro Visentini won than to his designated team leader - Roche insisted Carrera keep him.

Beyond the riders, Roche had the support of his mechanic, Patrick Valcke. The two knew one and other from their days at Peugeot. Between the three of them - Roche, Schepers and Valcke - they formed a team within a team. And when Roche felt he wasn't getting the full support of the rest of the team, that trio put their own game plan into operation.

Where Roche got the idea that Carrera weren't fully behind him - and when he started putting plan B in place - is worth looking at. The first sign was something he didn't even witness, but was reported to him by Valcke. When Visentini won the opening prologue time trail everyone on the team was delighted. But the response to Roche's victory two day's later in the descent of the Poggio was ... well Valcke told him it was muted, tinged with disappointment that Visentini hadn't bettered Roche's time.

It was on the sixth stage of the race that plan B started to come together. The stage finished atop Monte Terminillo, the mountain of Rome. Early into the day, Fagor's Jean Claude Bagot broke away on his own. Schepers went after him. The loyal gregario doing his job and protecting the team's interests. Except that a loyal gregario would sit on Bagot's wheel without doing a tap in front. Schepers did the opposite and drove the pace. And then, coming into the finish, he privately cut a deal: Bagot could have the stage if he rode for Roche - who, don't forget, was at this stage wearing the maglia rosa - later in the race.

Boifava knew there was something iffy about what happened on the road to the Terminillo. In an interview he gave after the race, quoted in Herbie Sykes' Maglia Rosa, he said this:

"That evening at Terminillo I spoke with Schepers because I understood immediately that something strange was happening. And do you know how I knew? When [the Gewiss rider Roberto] Pagnin went to join Schepers and Bagot, Schepers pulled to stop him getting on, then gifted the stage to Bagot. This was an irrational action for us, because in the first instance he should have been passive, just waiting in case Visentini or Roche would need help. Then, having worked to make sure Pagnin wouldn't make it up to them, he should have at least tried to win."

Schepers insisted to Boifava that he'd bought a favour for Carrera. And, at the time, Boifava had to believe him. Certainly, at that moment, Boifava didn't suspect that Schepers had really bought a favour for Roche.

The friction between Roche and Visentini was by now - just six stages into the race - becoming obvious. At one point, on the final climb to Terminillo, Roche had a gap of thirty seconds over his key rivals, including Visentini. But Visentini brought some of them back up and then refused to work to distance the others.

Roche complained publicly:

Roche complained publicly:

"When Visentini caught me with [Robert] Millar and [Marino] Lejarreta he would not work to open up the gap on [Phil] Anderson and [Moreno] Argentin, as I told him. It was an excellent chance to distance them, but for all that the day was not bad for me."

Though Argentin shed more than four minutes that day, he still saw hope:

"I still have a role to play in the Giro, despite all the time I lost. Roche and Visentini are at war with each other. Riders like Millar, Breukink and me can profit."

"I still have a role to play in the Giro, despite all the time I lost. Roche and Visentini are at war with each other. Riders like Millar, Breukink and me can profit."

Over the next few days, Visentini niggled away at Roche, shadowing him. Maybe Visentini was cuter than people gave him credit. He was messing with Roche's head. And it clearly worked, because in his autobiography Roche whines and whines and whines about Visentini's shadowing him in those early days of the race.

The feud between Roche and Visentini erupted after the race's sole rest day (two had been scheduled, but an election saw the second cancelled and the end of the race brought forward a day). On the tenth stage, the day after the rest day, Roche - still in the pink - decked it as the race sprinted into Termoli and Carerra's sprint specialist, Guido Bontempi, took down upwards of fifty riders. The next day, stiff and sore, Roche asked Visentini to take it easy. Smart move that, letting your rival know you're weak. Visentini put Roche under pressure throughout the stage and put time into him at the finish, cutting his deficit to just twenty-five of seconds. When the media quizzed him about what was going on, Roche tried to laugh it off: it was Visentini's birthday, he reminded them, Visentini was just trying to win the stage.

Then, two days later, on the road from Rimini to San Marino, in forty-six kilometres of uphill racing against the clock, Visentini wiped out his twenty-five second deficit on Roche. Actually, that rather understates Visentini's achievement. He put two minutes forty-seven into his team-mate. Now ain't that a kick in the nuts? The Italian donned the maglia rosa. The road had spoken.

The pre-race agreement was clear: let the road decide and then defend whoever was in pink. Boifava had brought the riders together the night before the San Marino time trial and reiterated the ground rules. Everyone agreed to play by them. Accordingly, Carrera would now defend Visentini's lead and, for the first time since Franco Balmamion in 1963, an Italian would win back-to-back victories in his home Tour.

How come Roche lost so much time that day? The bruising from his spill into Termoli played a role, yes. Crucially though, Roche identified Visentini's mind-games as the real reason he lost so much time in the contre la montre:

"Many times [...] I have tried to figure out what went wrong for me in the San Marino time trial. At the time, it was the most important time trial of my career, I liked the circuit, and the weather on the day was wet and windy, which should have suited me. [...] I believe that Visentini cracked me mentally. I am not sure that he deliberately set out to do this. But he did crack me."

Visentini's best bit of messing with Roche's head came before the time trial got underway. The two Carrera riders set out to reconnoitre the course, driving to it from the team hotel and stopping beneath a bridge to change into their riding gear. Roche set off. Visentini got back into the car. Then, when Roche had finished riding the full course - all forty-six kilometres of it - the Italian pestered the Irishman with questions about gears, and wind and all sorts of stuff.

"This went on all the way back to the hotel and when we got there it was time to sit down and have something to eat. I wanted to be alone but across the table Visentini kept asking me the same questions. Because he was my team-mate I could not say anything but inside I was burning up with anger. He was sneering and laughing, knowing that I was feeling the pressure of the pink jersey. He was relaxed, no nerves, and making jokes at me. It infuriated me."

Roche may have lost two minutes forty-seven to Visentini in that time trial, and the maglia rosaby two twenty-two. But he didn't lose the head. And - deal or no deal - he didn't admit he'd lost the race. He was still in second. The real Giro d'Italia had just begun.

Visentini:

"The Giro is not over yet. In fact I would say it has just started today. We still have some terrible mountain stages. On a bad day it will be possible to lose ten minutes, the winner will not be known until the last day at St Vincent."

Roche:

"I have not given up. There is another week to go yet. Now it is up to Visentini to take on the responsibility as race leader."

* * * * *

In identifying the various reasons he didn't like his Italian co-leader, Roche, in his autobiography, talks of the 1986 Baracchi Trophy. This was a two-up time trial, raced at the fag end of the season. It used to be a big deal but somewhere along the line lost its lustre, and then lost its place in the calendar. Roche had been resting since his dismal fall down the GC in the Tour, trying to nurse his knee back to fitness, the second bout of surgery on it yet to be recommended. He was teamed with Visentini for the Baracchi.

The two didn't even warm up together before the race, Roche's choice, he being concerned about his knee. Once the race got underway, there was no sign of the team-work needed to win a two-up. Visentini seemed to be riding against him, not with him, not giving Roche time to recover between pulls at the front. The Irishman felt that the Italian was trying to humiliate him in front of the tifosi.

But if Visentini was being a bollix that day, Roche gave as good as he got. In the second half of the race the Italian weakened. The Irishman paid him back in spades. Every opportunity he could find to shake Visentini off his back wheel he took. At the finish, Roche actually dropped Visentini and the two finished two hundred metres apart. In a two-up time trial. And they called themselves professionals?

That Baracchi was a race of two halves for the two protagonists. Now, reflecting on his dismal performance in the San Marino time trial and his loss of the maglia rosa to Visentini, Roche would have to make the Giro a race of two halves.

That night, in the team hotel, Roche was rooming with Eddy Schepers. Roche lay on his bed, his mind racing. Replaying the time trial. Refusing to admit that he deserved to lose the Giro because of one bad time trial. Schepers voiced the thoughts Roche wouldn't speak. He told him that Visentini didn't have the form, that he'd put too much into the time trial and would pay for it in the last week of the race, when they entered the Dolomites. Schepers reminded Roche of his own performance in the previous year's Tour, that good time trial ride and then his fall from second overall to nowhere.

The two looked at the stages to come in the Giro.

Roche reports his Belgian gregario identifying when would be the best place to put Visentini under pressure:

Roche reports his Belgian gregario identifying when would be the best place to put Visentini under pressure:

"Stephen, you must try something when he's not expecting it and I think the Sappada stage would be the best. He isn't going to recover easily from the efforts in the time trial and it's better to try something as soon as possible."

Sappada was just two days away, following a dull flat stage where the sprinters could feast and the GC contenders recover. It marked the race's entry into the Dolomites, and was followed by the race's tappone, the Queen stage, five tough climbs, including the Pordoi, the highest climb in that year's race, and finishing on the Marmolada. Tough as the Sappada stage was, everyone assumed that the real threat lay on the road to the Marmolada and that the peloton would take it easy on the road to Sappada. Roche and Schepers, plotting to bring about the downfall of Visentini, decided to catch everyone off guard. Schepers was right. If 'twere done 'twere best done quickly. Roche would plant the knife in Visentini's back on the road to Sappada. The knife turned out to be almost six minutes long. Roche rode his was back in the maglia rosa.

* * * * *

Sunday, June 6th 1987. That was the day the deed was done. Forcella di Monte Rest (1,052m). Sella di Valcalda (959m). Cima Sappada (1,286m). All contained in 224 kilometres of racing, the first hundred relatively flat. Jean-Claude Bagot, the Fagor rider Schepers had done a deal with, attacked on the Monte Rest. Robert Millar, who was riding for KOM points, defending his green jersey, went next. Robert Conti (Selca) went with him. Roche went after them. Visentini got back up to them before the top of the climb but then Ennio Salvador (Gis) attacked. Salvador was twenty minutes down on GC, no threat to anyone, but Roche seized the opportunity. It was on the descent that the real damage was done.

"I made an unbelievable descent, went downhill with the back wheel up in the air."

Behind him was confusion.

"Fellows were hanging out of trees, having overshot corners. Visentini missed one turn and was forced to take a short cut down one gravel bank to return to the road."

In the valley, Roche and Salvador joined up with Bagot, who was still up the road, but he punctured and slipped back into the peloton. Roche helped Salvador drive the pace. Just like Schepers had helped drive the pace on the Terminillo earlier in the race. And just as that day, the Carrera direttore sportivo, Davide Boifava, got pissed off. He drove up to Roche.

Here's Roche's recollection of the conversation:

Here's Roche's recollection of the conversation:

- Hey, Stephen, what are you doing?

- Just riding along, waiting for the other teams to ride after me.

- But Stephen, the other teams are not chasing you.

- Well, then, that's their bad luck. If they're going to let me take twenty minutes, they'll lose and Carrera will win.

- But if you keep riding you will take twenty minutes and win the Giro.

- That's what I want.

- Why don't you just sit behind Salvador, let him do the riding and try to win the stage?

- Salvador is going nowhere. He is creeping. Anyway, it's not the stage I want. It's the Giro.

- Stephen, Visentini has the jersey. You cannot do this to Visentini.

- Look, Visentini is behind. Somebody, the Bianchis, the Panasonics for Breukink, some team is sure to ride after me. Just wait a minute.

- No, Stephen, the Carrera team is riding after you.

- What?

- The Carrera team is chasing you.

- You go back and tell the boys that if they're going to ride behind me they had better be prepared to ride for a long time and that they should keep a little bit under the saddle because when they catch me, they're going to need it.

The seventieth Giro d'Italia had just turned from drama to farce. Carrera were leading the chase of their own rider. A chase other teams should have been leading. And which, later, both Breukink and Millar told Roche Panasonic would have headed had not Carrera beat them to the punch. Roche was happy:

"For me, this was an exploit. Something big. I distinctly remember I was smiling on the road to Sappada. I could not feel any pain. I was so angry with everybody else and so happy with myself. Happy that I could do what I was doing."

Jean-François Bernard (Toshiba) and Phil Anderson (Panasonic) jumped across to Roche. Roche sat in behind them. More riders got up them, including Millar. But not Visentini. The group was maybe a dozen or so riders, and now included Toni Rominger, who was just thirty seconds behind Roche on GC.

Boifava dispatched Roche's mechanic, Patrick Valcke, who was riding in the second team car, to talk Roche down and bring him back under control. He passed on his boss's request. Roche politely declined. Boifava wanted to speak to Roche over the team radio:

- Stephen, this is Boifava. You must stop.

- Tell the team to stop and I'll stop. Not before.

- I can't do that.

- Well then I can't stop.

- Stephen, if you don't stop I will come up personally with the car and push you off the road. This is not possible. Everyone is laughing.

- It's not me they're laughing at but you. Tell the boys to stop riding, it's not right to ride after a team-mate. I've been playing the role of joint leader in the Carrera team for the last two weeks now and when I have a chance to win you're telling me to stop. Tell the boys to stop and I'll stop.

- No, no, Stephen. You stop or I will take drastic action.

- You can do what you want.

So much for Roche's version of events. How did Boifava remember it? Here he is speaking to Tuttosport's Beppe Conti, years after the fact, quoted in Maglia Rosa:

"I went to see him in the team car and asked his reason for what he was doing. He told me that he only wanted to win the stage. I told him that if this was his objective he should just sit in and stay in the wheels. Instead he continued to pull, to keep the pace very high."

Johan Van der Velde (Gis) went clear from Roche's group and took the stage. Behind him, forty-six seconds later, came Toni Rominger (Supermacati), Flavio Giupponi (Del Tongo), Robert Millar (Panasonic), Erik Breukink (Panasonic) and Pedro Munoz (Fagor). Ten seconds later came Steve Bauer (Toshiba), Roberto Conti (Selca), Mario Beccia (Remac), Peter Winnen (Panasonic), Alessandro Pozzi (Del Tongo). And Roche. Another six minutes elapsed before Visentini crossed the line. Roche was in the pink, Visentini was in seventh, three minutes twelve down. And in second there was Rominger. The ten second time gap to Roche at the finish was augmented by bonifactions meaning Rominger was now just five seconds behind Roche. Breukink was within thirty-eight seconds. Millar was at one fifty-eight. It was tight at the top.

What had happened to Visentini?

Boifava:

Boifava:

"I told Visentini that Roche wasn't working, so as not to upset him. I tried in vain to keep him calm, but I couldn't. His nerve completely deserted him."

Visentini blew a gasket climbing Sappada. He blew a fuse after the finish. Certain people would be going home that night, he promised the media. The sceptics among them probably wondered if he meant himself, given what had happened in 1984 and 1985. The rest knew he was referring to Roche, Schepers and Valcke.

Roche, interview by l'Équipe, was unapologetic:

"I have nothing to be ashamed of. When I set off after Salvador, I didn't work and I didn't work when there were a dozen of us at the front. But when [Patrick] Valcke brought the instructions from Boifava, I saw red. I knew that the whole team was working behind me; I couldn't carry on not working."

Boifava was well and truly pissed off by Roche's antics. And justifiably so:

"[In the hotel, Roche] started to tell me that he hadn't attacked, that his actions had been for the benefit of the team, but I cut him short immediately. I told him that I didn't want to hear his stories. We'd had the jersey by over three minutes from Rominger, who was third. Now, because of his actions, we were not only a laughing stock, but we had only five seconds."

* * * * *

Back home in Ireland, we held our breath. Five seconds. Nothing. And the finish still a week away. So much could go wrong. We knew. Only nine days before the Giro d'Italia started, Sean Kelly had been leading the Vuelta a España only to be forced to abandon just three days from Madrid, saddle sores denying him a Grand Tour victory. We crossed our fingers and held our breath.

In Italy, the tifosi were not holding their breath. The tifosi were not pleased. Not pleased at all. At Sappada, as Roche slipped on the pink jersey, the tifosi booed him. Roche was the worst kind of traitor. A foreign one. And the next day, on the road to Marmolada, they left Roche in no doubt as to their displeasure.

That Roche started the stage was down to Carrera boss Tito Tacchella who flew in to the Giro to broker peace talks within his squad. He was meant to be arriving to resolve the outstanding issues with regard to Roche's contract. Visentini was put in his box and told to take one for the team. Roche was put in his box too and told not to talk to the media. Even Schepers and Valcke agreed with this and gave the Irishman the same advice.

As punishments go, this was cruel and unusual. These were the days of the Foreign Legion. New audiences in the English-speaking world were discovering cycling. English-speaking journalists were covering the sport. And what they most needed was riders they could talk to. Preferably in English. Robert Millar would ride past them. Sean Kelly could cut them down with a glance. But Roche always found time for them. Point a microphone at him and he'd talk. Point a camera at him and he'd smile. Roche loved the media and the media loved Roche. And here he was being silenced. Or not, as it turned out:

"I knew that silence from me was a confession of guilt. I was not prepared to stay silent and did not."

Having won back the maglia rosa, Roche now had to defend it. And he had to defend not just against attacks from Toni Rominger, Erik Breukink and Robert Millar, he had to defend it against attacks from Roberto Visentini. On the road to Marmolada, Roche covered every move Visentini made. But the real problem faced by Roche that day came from the roadside fans. On the road, the tifosi hurled abuse and more at Roche.

Much is made of this, and it is true, the Italian fans that day were the unpleasant face of cycling fandom. It was a Sunday, and so the crowds had time on their hands. They were whipped up by the previous day's stage and the polemica that ensued.

Here's how Panasonic's Robert Millar explained that day to Winning:

"Yes, they had a lot of problems with crowd control in the mountain stages, and I'd been in the same situation myself in Spain, not as serious as it was in Italy the day after Stephen had taken the jersey from Visentini - people were really hostile and I'd never seen anything like it before. Something similar in Spain yes, but only in isolated pockets of maybe ten or twenty people in a certain place, but not two or three thousand people all waiting on a mountain just to beat the shit out of you and spit on you."

Roche tells it this way:

"Eddy and Robert Millar were protecting me on the climbs, riding at either side of me. Without the two lads that day, I do not believe that I would have got through the Giro. As Bob was a member of a rival team, Panasonic, I was particularly grateful to him for giving me a dig out that day. We have been close friends for a long time and I was very happy to have him close to me on that day. The behaviour of the people was bad. As well as the punching and pushing, they were spitting wine at me. There was also some kind of grain that they were spitting at me. At the finish I was really dirty from the stuff they had spat at me."

As bad as the tifosi were that day, the physical danger came from Visentini. After the stage, one journalist asked if it was true that Visentini had tried to put Roche and Schepers on the ground. Roche tried to deny the story. Only for Visentini himself to chip in:

"I tried to put them on the ground and the next time I'll use my fist instead!"

Kerching! Pay fine of three million lire. Not a chance, said Visentini. Lose your licence, said the authorities. I'm not paying it for him, said Boifava. No payment, no licence, said the authorities, and no licence, no start tomorrow. Visentini had to get his wallet out.

The best thing about that day? Rominger shipped more than a minute, seemingly without Roche even having to make an effort to hurt him. The GC was now Roche, followed by Breukink (thirty-eight seconds) and Millar (a minute fifty-eight).

Six days of racing remained. Mountains alternating with sprints and then the final race of truth. But they were just physical obstacles. Physical obstacles can be overcome. What of the mental? Visentini had chipped away at Roche during the first two weeks of the race and all but broken him on the day of the San Marino time trial. Roche had struck back and broken Visentini on the road to Sappada. But was he himself now strong enough to survive the rest of the race?

Here's how Roche described those last few days of the race, speaking in Dublin a few days after the race ended. By then he'd been reunited with his two children, Nicolas and Christel, and was able to joke a little about the Giro, joke about himself, laugh at how different he was from the hard-man Sean Kelly:

"I'm a softie from Dublin, I wasn't brought up in Carrick-on-Suir! So I have always been nice on the bike, that's my nature. I've never got involved or thrown shapes the way Sean Kelly throws shapes. That's his way. He's all tough and hard but I've been nice.

"I've been pleasantly surprised how tough I was during the Giro. You never really know until you're tested. I found it frightening at times. The fans were punching me, filling their mouths with wine and spitting it over me, hitting me. At night, for part of the race, I had to stay in my hotel room and eat there. Downstairs the lobby would be filled with fans with anti-Roche banners. I'd get phonecalls. Most of them were of support but some were threats.

"It really got to me. I was leading the race for eighteen days and that didn't worry me. But the other pressure was very heavy and every day the papers were full of scandal stories. By last Thursday I was nearly at the end of my tether. Then my wife, Lydia, came over from Dublin. She helped me steady myself up for the Friday, which was a very important stage.

"And the only thing I kept saying to myself when things were very rough was that I wasn't going home. They weren't going to make me go home."

Throughout that last week, Visentini kept up his war of words. But Roche was silencing him on the road. Pockets of tifosi kept up the abuse, but Roche was riding through the mental storm. Visentini was increasingly marginalised and sounding more and more paranoid. But just because you're paranoid ... when Visentini accused Robert Millar and the Fagor team of Jean Claude Bagot of riding for Roche, he was spot on. That deal put in place on the Terminillo stage was important. And the support asked for from Millar too. The Scot was only interested in the KOM jersey, and maybe a stage win. He protected Breukink's second place, but he also helped protect Roche.

Soon, even the Carrera riders forgot Sappada and put if not their hearts then certainly their legs behind Roche. Visentini's end was ignominious. A fall on the penultimate day saw him break his wrist and fail to start the final stage. The only change in the GC came that same day when Millar got his stage win and leap-frogged his team-mate, Breukink, to claim second.

On that Friday night, Sean Kelly called Roche from Grenoble. Roche could still blow it on the final day's time trial. Kelly, who knew what it was to have a Grand Tour victory snatched from his grasp - Kelly who'd snatched away victory in Paris-Nice from Roche's grasp on the last day of the race only three months earlier - gave his friend and rival a pep talk. The next day Roche rode the race of truth the way he should have in San Marino and sealed victory in the Giro with a second stage win.

Francesco Moser, who'd missed the Giro through injury, acknowledged Roche's victory:

"He has finally won a great stage race. What had merely been a promise that might never have been realised has come true."

The Gazzetta - having stoked the polemica earlier in the week - rowed in behind Roche:

"We can now call him Stefano: the crowd has adopted him."

And Visentini?

Visentini was down, but refusing to bow out:

Visentini was down, but refusing to bow out:

"There are many versions about what Roche is going to do next season and some reports say he has already signed for another team. That doesn't matter. The important thing is that where I race he doesn't. Otherwise something really serious could happen."

Three hours after Stephen Roche won the seventieth Giro d'Italia he climbed into a Peugeot car with his wife Lydia and drove through the night, back to Paris. Eddy Schepers followed in another car, Patrick Valcke alongside him. The Carrera team could celebrate without them. Forty-four days later, Roche stood on a podium on the Champs Elysées, Charles Haughey, the Irish premier, at his side, celebrating his victory in the Tour de France. A little over a month later, Roche donned the rainbow jersey.

Made it ma, top of the world.

* * * * *

David Walsh, who ghosted Roche's autobiography, was at the 1993 Tour de France, Roche's thirteenth and final year as a pro. In his book about that race, Inside the Tour de France, Walsh gave-over a chapter to the story of Roche's last hurrah. In it, Walsh imagined a conversation forty years forward, a seventy-something Roche and a grandchild:

- What was it like to win the Giro, the Tour and the World Championship in one year? You must have been something? They say the Italians spat at you during the Giro, that you collapsed at the end of a stage in the Tour? Did the Irish prime minister really come to congratulate you? Back in Dublin, did a quarter of a million people welcome you home?

- Yes, all those things happened. I can show you the pink jersey I won in Italy, the yellow I got here in France and the rainbow jersey of world champion. They were what I wanted.

- Really granddad?- No, I suppose they weren't.

- Didn't they make you happy?

- Ah, that's a long story.

* * * * *

Sources:- My Road to Victory, by Stephen Roche (ghosted by David Walsh);

- The Agony and the Ecstasy, by Stephen Roche (ghosted by David Walsh);

- Inside the Tour de France, by David Walsh;

- Maglia Rosa, by Herbie Sykes.

Commenti

Posta un commento