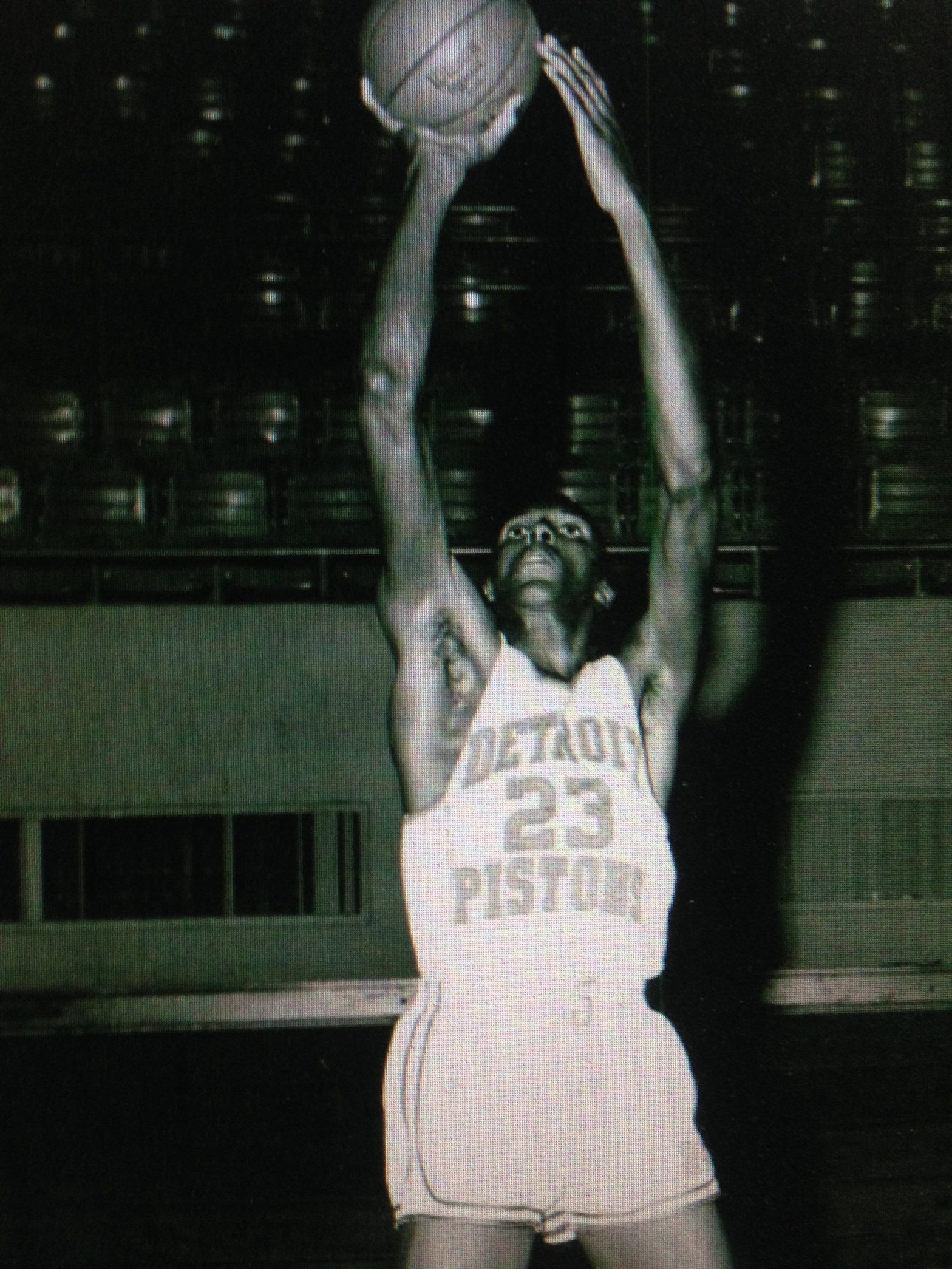

The Two Faces of Walter Dukes, 1963

Posted by bobkuska October 11, 2021

Posted in Uncategorized Tags:1960s NBA, Detroit Pistons, Dick McGuire, Don Ohl, Hal Butler, New York Knicks, Nick Kerbawy, Red Rocha, Walter Dukes

[In the late 1970s, New York sportswriter Phil Pepe wrote a column about Walter Dukes. As many in New York remembered, Dukes had starred on the hardwood for nearby Seton Hall in the 1950s, and the Knicks grabbed him in the 1953 college draft, ready for his lean, 6-foot-11 frame to serve a cornerstone for a future NBA title. “I was asking for $20,000 [rough;y $200,000 today],” Dukes remembered his negotiations with the Knicks. “I had an offer from the Globetrotters for $55,000, but I was willing to take twenty from the Knicks because I wanted to play in the NBA. We got hung up over $3,000.”

The hang up forced Dukes onto the vaudeville circuit with the Globetrotters for two years. But he eventually signed with the Knicks for the lower working wage, then hurt his knee in his rookie season. The Knicks quickly unloaded Dukes, but he and his famously sharp elbows hung around the association for eight seasons, mostly in Detroit.

In this article, which appeared in SPORT Magazine in January 1963, writer Hal Butler profiles “Big Waldo,” as he was known, in what would be his final NBA season. The Pistons tried to trade Dukes after the summer but had no takers. So, in October 1963, Detroit cut him to make way for, drumroll please, the legendary, pistol-packing seven-footer Reggie Harding.

“I wouldn’t have minded being let out,” Dukes complained, “if they had warned me ahead of time. But nobody said a thing to me about not playing until just before the training camp opened in September . . . and that froze my expectations of income.”

The 33-year-old Dukes had other professional interests, including a budding legal career, and would survive just fine without the NBA pay. But trouble always seemed to complicate Dukes’ life in the NBA, and the same was true after his pro career. Dukes would be charged with practicing law without a license. As always it was a silly misunderstanding. Then, Dukes would be involved in a car accident that left him paralyzed for more than a year.

When Pepe caught up with him in 1978, Dukes was back on his feet and serving as an assistant basketball coach at little Hunter College. He still got an occasional earful from his critics, who considered Dukes to be, well, an NBA wash out. “I’ve heard that, but I can’t agree with it,” Dukes said. “I made the all-star team twice, I played eight years in the league, what do people expect you to do? Don’t forget, I played in a time when there were two pretty good centers in the league named Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain. Everybody can’t be a Russell or a Chamberlain.”

Neither has the NBA seen many seven-footers like Walter Dukes, on and off the court. Here’s his story]

A nurse measures Dukes.

The owner of two of the most terrifying elbows in pro basketball violently cut a swath through the crowd beneath the basket. Detroit and Cincinnati players parted like the Red Sea and seven-foot Walter Dukes flailed his way toward his objective—a rebound. Walter got the ball, but his conquest didn’t ease the pain of Piston teammate Dick McGuire, who had just been lacerated by a Dukes elbow. Staggering to the bench, McGuire shook his aching head. “There are times,” he said, “when I think I’d just as soon play against Dukes.”

That was five years ago. McGuire has since retired to the Detroit bench as coach, but the mayhem goes on. Late last season, Detroit’s Don Ohl left a game early to have three stitches sewn above his eye after a mix-up under the basket.

Piston publicist Fran Smith frantically followed Don into the locker room.

“Who hit you?” he asked.

“Who do you think?” said Ohl. “Dukes.”

Such are the perils of playing with, much less against, the man who is variously called Walter, Wally, Waldo, or Big Waldo. Reminiscent of a windmill gone berserk, Dukes appears to be a freakish and uncoordinated athlete with no noticeable brainpower. Fans tend to think of him as an NBA hanger-on who may someday drift into oblivion because he lacks other talents. In reality, that’s the oncourt face of Walter Dukes and is only a distant relative of the non-playing man.

Holder of three college degrees, Walter owns a travel agency in New York, is a partner in a real estate firm, and has been admitted to the bar in Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania. That’s the other face.

Soft-spoken and careful of the words he uses, Wally considers himself only an average basketball player. He would much rather talk about his business ventures, as he did when a man from SPORT visited him recently in his bachelor apartment in Detroit.

First, however, Wally answered the critics who say that too many interests spoil the player. “I see no conflict between outside interests and playing pro basketball,” he said, stretching out among the books, papers, and brochures cluttering his living room. “In fact, I believe that if an athlete is happy and pursuing other interests in life, he will do a better job in his sport, too.”

Though his three extracurricular activities demand a great deal of time and energy, Dukes has tied them together to minimize handling. “For example,” said Wally, “I’m sole owner of the Vista Travel Service in New York City, which specializes in unusual trips like African safaris. We have connections with guides in the Italian Somaliland who will fully equip and lead safaris on hunts for elephant, rhinos, lions, and other big game. If a man wants to go on safari, we usually fly him into Liberia and set it up for him to take a private plane from there into the bush country. Here he makes contact with the guides who lead the safari.”

Dovetailing this is Dukes’ work with the Philadelphia law firm whose senior partner is Harold E. Stassen, former Minnesota governor. Wally is an employee of the firm’s African Affairs Bureau and helps handle advertising, publicity, and legal matters for the various countries.

“Even the real estate agency in which I’m a partner ties in well with the travel agency,” he says. “We buy and sell properties, like any real estate agent, but we also work as a broker for new and old travel agencies.”

All this still is not enough to keep Dukes’ fertile mind fully occupied. “I spend a lot of time on patents and domestic relations,” he says. “The latter is something I sort of drifted into because it was a convenient phase of law to practice while playing basketball. But international law is the thing that most fascinates me. This is the phase of law I hope to someday end up in. Right now, I’m at a juvenile stage in this and have a long way to go, but I’m learning every day.”

Because his several interests leave little time for frivolity, Dukes has the reputation of being a loner. Except during practices, games, and team travel, he sees almost nothing of his teammates. Even when the team is flying, Duke’s usually is by himself, studying travel folders or legal documents.

“I admit I’m a loner,” he says, “but there are reasons. When the season first gets underway, I play cards or go to the movies with the fellows. But after doing this for a while, I begin to want something different. Sometimes, I want to be alone just to think. Sometimes, I have law studies or business on my mind when we’re traveling and want to be left alone.

“My size and sleep habits make me a loner, too. I’m seven feet tall, wear a size 50 extra-long suit, and size 15 shoes. I have a seven-foot bed at home, but on the road, I need a double bed in my room so I can sleep diagonally. To get this, I have to have a room to myself.

“Lots of guys like to get up early in the morning, too, but not me. I enjoy reading late at night, and I sleep well into the day. I’m the reverse of most. And, of course, when we’re in Philadelphia or New York, I have business contacts to make. All of this added together takes up a lot of time away from the team.”

The worst reputation Dukes has, of course, is that of a wild maniac who someday may mistake opponent’s head for the ball. Records show that Wally has earned his notoriety. Since joining the Pistons in 1957, he has committed 1,593 fouls and fouled out 95 times. He also had led the league twice in total fouls—311 in 1957-58 and 327 in 1961-62.

The spectacle of Dukes leaving the floor after fouling out is so humorous to Detroit fans that they cheer him as if he had accomplished his night’s objective. Yet, without their center the Pistons sputter. One of the best rebounders in the NBA, he is the hub of the Piston defense. He has led Detroit three times in rebounds and is usually among the league’s leaders. Says teammate Bailey Howell: “I don’t know what we’d do without him. He gets a hand on every ball that goes up, and he either grabs the rebound or keeps it alive around the enemy basket.”

Dukes (6) in his season as a Knick

But rebounding is a subtlety of basketball the casual fans tend to overlook in favor of high scoring. Dukes’ tornadic style looks haphazard and ineffective to them and, as a result, Wally himself appears to be not only a poor player but a somewhat unintelligent human being.

Unfortunately, Dukes has been involved in some heavily publicized incidents that do little to dispel this illusion. In 1958, for example, the Pistons had scheduled an exhibition game in nearby Lansing, and team members were asked to drive their own cars. All the Piston players arrived except Dukes. Red Rocha, then coach of the Pistons, was not especially disturbed at first since Dukes rarely arrives anywhere with more than a minute to spare, more-often minutes late. But when practice ended and Walter still had not shown up, Nick Kerbawy, then general manager, called the Michigan State Police.

“If you see a seven-foot center between Detroit and Lansing, bring him in,” said Kerbawy.

Dukes, however, was nowhere between Detroit and Lansing. He had originally driven to Flint. When he found the Flint arena dark, he assumed the game had been canceled and drove back to Detroit—slightly miffed at the club for not informing him.

The next year, Dukes failed to make it to Detroit for his preseason physical exam. He already had signed his contract and had been sent a schedule for the training period. The Piston management couldn’t understand his absence. The club called his residence and business office in New York City, his mother in Rochester, and his sister in Elizabeth, New Jersey. The Pistons had enriched the phone company by $200, and they still were without their center.

Ten days later, they received a call from New York. “I understand you were trying to find me,” Dukes drawled. “What’s the difficulty?”

The Pistons patiently explained that he was 10 days late for practice.

“Gosh, you mean it’s time to play basketball again?” he exclaimed. “Where did the summer go?”

At the beginning of the 1959-60 training season, Wally came up with a brand-new excuse for his tardiness. Just before he left camp, thieves broke into his car and stole 17 suits. “Must have been some awful tall thieves,” he said. Again, Dukes was delayed, buying a new wardrobe.

When at last he reported, he traveled with the Pistons to Minneapolis for an exhibition game. Wally had not yet signed his contract, but no trouble was expected. He played the game, unceremoniously boarded a plane and flew back to New York, leaving behind a “no-contract, no-play” edict. He missed the first seven league games while he held long-distance negotiations with the club.

On another occasion, Dukes parked his car improperly before a Piston practice. When he came out, he found the car gone. Police had towed it away after finding 22 unpaid traffic tickets in the glove compartment. Once more, Dukes made sports-page headlines.

Wally saved his biggest encore for a tough regular-season game with the Lakers. Normally placid, Dukes exploded when a foul was called on him in the third period. Wheeling around, he muttered something to the referee and stalked angrily off the floor and into the dressing room.

Coach Rocha dashed after him and found Dukes pulling off his shoes. “What’s the matter, Wally? You get kicked out of the game?” he asked.

“No.”

“Then what are you doing?”

“Red,” said Dukes with strained patience, “I’m not going back out there. I can’t play with that refereeing.”

Wally got dressed and watched the rest of the game from the stands.

Understandably, Dukes is tired of being the butt of so many jokes. “Nobody else seems to get the publicity I get when something happens,” he complains. “When showing up at the wrong place or being late happens to me, everybody gets excited. It happens to other guys, but they never seem to get the publicity. Also, I’ve mentioned that the newspapers don’t always tell the whole story. If they did, it would spoil their punchline.

“For example, when I went to Flint instead of Lansing, it was because I had first gone to the Piston office and asked one of the secretaries where the game was being played. She told me Flint. But that was never explained. I was made to look like an idiot for going to the wrong town. Once in college, a big story was written about how I’d forgotten to bring my shoes to a game and had to play in my bare feet. The truth was, the trainer who was supposed to pack them didn’t. But I got the blame.

“About those 22 traffic tickets, they weren’t even mine. I had loaned my car to some friends, and they got the tickets and put them in the glove compartment.” (Club officials back Dukes up. Fran Smith says, “Dukes is so generous, he’ll loan his car to almost anyone. I don’t think any of those tickets were his.”)

“I will admit to being late sometimes, though,” Wally conceded. “I have a lot of things on my mind, and I sleep late hours. Sometimes, these things disrupt my schedule.”

Dukes in college

Dukes didn’t have much on his mind on June 30, 1930, and so he said hello to the world right on schedule. He was the youngest and, not surprisingly, the tallest of five children of a Youngstown, Ohio, construction engineer. But not until the summer before Waldo entered high school did he begin to show signs of becoming Big Waldo. “I was about 5-foot-10,” he says. “I went to summer camp in Canada with the Boy Scouts and came back 6-foot-3. Must’ve been that fresh air, I guess.”

In high school, Dukes was an all-round athlete. When Wally entered Seton Hall, he had narrowed his sports participation to basketball and track. In his freshman year, he ran a 1:58 half-mile and anchored the winning Seton Hall mile-relay team in the Penn Relays. “I tried high jumping, too,” Dukes says, “but I kept landing on my back. My basketball coach told me to give it up before I killed myself.”

In 1952-53, he averaged 26 points a game, was chosen All-America and led his team to 27 straight wins and the National Invitational Tournament championship. Unimpressed by the salary offered him by the New York Knickerbockers, who had drafted him in 1953’s first round, Wally signed instead with the Harlem Globetrotters.

Within two years, though, Dukes’ curiosity about the world apparently had been satisfied and he was willing to settle for the Knicks’ lower pay. He played one season with New York, injured his knee, and was sold to Minneapolis. A year later, in September 1957, he was traded to the Detroit Pistons for center Larry Foust and $5,000.

Despite his defensive skills (he had 5,863 rebounds with the Pistons prior to this season), Dukes has too many faults to be rated a great player. His low scoring in particular has frustrated Detroit fans. In his top scoring year, 1959-60, he averaged 15.2 points per game. But last year, he dropped to 9.3 and his career average is only 11.2.

Dukes’ awkward ballhandling also is upsetting. He breaks up fastbreaks—his own team’s—by throwing the ball away. Often, he will miss passes thrown to him, especially short, quick ones, and, even with his height, he rarely blocks an opponent’s shot.

Piston officials are aware of these shortcomings, and they think they know the reasons. “Dukes has poor eyesight and weak hands,” says Fran Smith. “That’s why he misses those quick passes—his eyes won’t pick up the ball fast enough, and his limp hands won’t hold the ball thrown fast. The same two reasons usually prevent him from scoring or tapping the ball in when it is alive around the basket.”

Despite his flaws, Dukes has many values. His chief asset to the Pistons is as an intimidator. A 220-pounder who plays the ball all the time. Wally isn’t too concerned about who gets in his way. Once Dukes hits a man in a scramble for the ball, that man is likely to think twice before trying to go around, through, or over him again.

Since only the players know how grueling a duel with Dukes can be, it isn’t surprising that Wally’s greatest tributes come from them. The St. Louis Hawks’ Bob Pettit says, “I have the greatest respect for Wally. He has tremendous desire and works as hard as anyone I know. He’s a terrific rebounder and about as good as they come on defense. He’s mighty rough—he has the sharpest elbows and knees I ever saw. But he can take it, too, and he never whimpers.”

When Waldo was traded to Detroit in 1957, George Yardley, then the Pistons’ high scorer, was one of the most-elated players in the NBA. “Now,” he said, “I won’t have to worry about going out there and running into Dukes every five or six games.”

Wally’s value to the club was illustrated most vividly during the 1960-61 season when he injured his foot and missed nine games. The Pistons were battling for second place, and Dukes had been averaging about 11 points per game. Bob Ferry substituted for him and scored 25 points a game. But the Pistons fell apart defensively. They lacked the rebounding Dukes had been giving them and lost seven out of the nine games.

Assistant coach Earl Lloyd says, “When Dukes is out of there, we might as well quit. But the fans don’t understand this—they just think he’s a big rough goon.”

Dukes isn’t especially proud of his roughneck reputation, but neither does he sound like a guy who wants to play Ferdinand the Bull. “Most big men are considered rough if they have fast movement,” he says. “Anyone swinging arms on a basketball court is going to hit and bump people. There’s always a blind side, and if you make a quick move toward one player, you’re apt to bump somebody on that blind side.

“Also, a big man can’t stop as quick as a smaller man, resulting in more collisions. I think, too, that if you are a center you have more opportunity to bump opposing players around—and also to get hurt yourself—than at any other position. At center, you’re standing still much of the time, right in the middle of a whirlpool of action, where players are breaking, faking, drifting around. Out of five opposing players, about three will be concentrating around center. You make a quick move and somebody gets hit. I really believe center is one of the toughest positions to play.”

Although Dukes rarely argues with referees on the court, he privately believes there are too many fouls called on him. “Most fouls are discretion calls,” he says, “but I feel there has been many called against me that were doubtful.” Maybe, because a center is stationary much of the time and because I’m a big man, I’m easier to watch.”

Dukes is probably right. Veteran referee Jim Duffy once said, “We don’t watch Dukes more closely than other players. But when a man his size belts somebody, it’s noticeable. I don’t think it’s intentional with Dukes. He just doesn’t watch what he’s doing. He plays that ball all the time and doesn’t seem to care if he creams a teammate or an opponent.”

While handing out such mayhem, Dukes has been required to take some, too. As a pro, he has broken his jaw, lost three teeth, fractured a finger, torn the cartilage in both knees, broken his toe, chipped his elbow, and collected sundry bumps and bruises. “You’ll notice,” he says, “that it is usually the centers who get hurt.”

Dukes earned close to $20,000 a year with the Pistons, about half his total annual income. With his education, his business interests, and his ability to make money outside of sports, why does he even bother with basketball?

“I like the game,” he says simply. “Even though I’m busy with outside activities, they actually come second at this point. When you’re an athlete, you instinctively know you won’t go on forever. So I make the most out of basketball now, while I can still play and enjoy it. The other activities I’ll have more time for later.”

How little the typical fan appreciates Dukes’ value to the Pistons was shown last season when a writer told a stranger in the stands he was preparing a story on Wally.

“Him?” the guy squawked. “What are you gonna write about him?”

The writer mentioned Dukes’ defensive abilities, but to no avail.

“You better write that he won’t be around next year if you don’t sharpen up and start scorin’ some points,” said the man.

Fortunately, the Pistons don’t feel that way. They know that the gangling Dukes is a defender they sorely need. “He controls the ball for you,” says coach Dick McGuire, “and this is a ball-control game.”

As long as Dukes performs this function, the Pistons aren’t too concerned about how he looks doing it. It doesn’t matter to them if the fans think he’s rough, awkward, or just plain dumb—providing he picks off some 1,000 rebounds each season. Perhaps it doesn’t really matter to Dukes either. He must certainly be aware that his public and private images differ widely. He must also know that a peculiar character has more value at the box office than a lawyer. But he likes to pretend none of this ever has occurred to him.

When asked how he felt about having two distinct faces, he smiled quizzically. “I really don’t know what you mean,” he said.

Sure, Waldo.

Commenti

Posta un commento