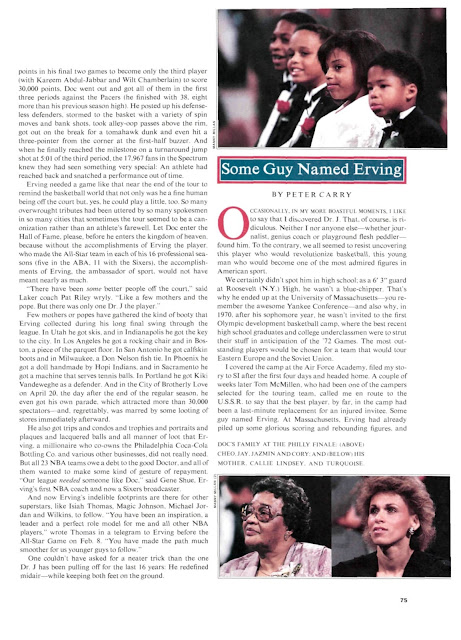

SOME GUY NAMED ERVING

Occasionally, in my more boastful moments, I like to say that I discovered Dr. J. That, of course, is ridiculous. Neither I nor anyone else—whether journalist, genius coach or playground flesh peddler—found him. To the contrary, we all seemed to resist uncovering this player who would revolutionize basketball, this young man who would become one of the most admired figures in American sport.

We certainly didn't spot him in high school; as a 6'3" guard at Roosevelt (NY.) High, he wasn't a blue-chipper. That's why he ended up at the University of Massachusetts—you remember the awesome Yankee Conference—and also why, in 1970, after his sophomore year, he wasn't invited to the first Olympic development basketball camp, where the best recent high school graduates and college underclassmen were to strut their stuff in anticipation of the '72 Games. The most outstanding players would be chosen for a team that would tour Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

I covered the camp at the Air Force Academy, filed my story to SI after the first four days and headed home. A couple of weeks later Tom McMillen, who had been one of the campers selected for the touring team, called me en route to the U.S.S.R. to say that the best player, by far, in the camp had been a last-minute replacement for an injured invitee. Some guy named Erving. At Massachusetts, Erving had already piled up some glorious scoring and rebounding figures, and that summer he would excel at a higher level of competition, but you had to be in certain places, like Colorado Springs and Minsk, on certain days to see him do it.

In the spring of 1971, Dr. J, then 21 years old, was among the first players to "go hardship"—the hardship being not so much that of the players but of the tottering American Basketball Association as it tried to compete with the NBA for the best young talent. Among the ABA's feebler franchises were the Virginia Squires, whose coach, Al Bianchi, hadn't had so much as a glimpse of the Doctor until the postsigning press conference. Then he got an eyeful. Said Bianchi: "As we left the room, I turned to the president of our team and said, 'My God, did you see those meat hooks!' "

It wasn't his mitts that most impressed me when I ventured to Virginia that fall to write a story on Dr. J—and thereby stake a claim to a discovery as fraudulent as Amerigo Vespucci's. While I interviewed Erving, I noticed that when we were sitting next to each other he wasn't that much taller than I was, and I'm 5'11". What we had here was a six-footer's body with gams that went on forever. As Dr. J said, "I guess I consider my hands my best physical attribute, but I don't like to forget my legs, either."

What the fortunate few who saw Erving perform for the Squires before sparse crowds in places like Hampton and Memphis and Greensboro don't like to forget is...well, everything. In a league without imposing centers, the Doctor could do as he pleased, which mostly meant taking the ball to the hole with impunity and ingenuity. My favorite moves came on the defensive boards where Dr. J could actually pluck the slippery ABA ball out of the air with one hand while it was moving away from him. He also took to rebounding one-handed with an arm extended behind him so he could propel himself downcourt to start the break. And there was never anything like the young Julius in the open court—huge strides eating up the hardwood, mammoth hands swallowing up the ball before slamming it through the hoop.

That Dr. J's heroics, not to mention his unfailing gentle-manliness, were largely unknown to the rest of America was hardly startling—he appeared on national TV in games that meant anything only twice during his two years with Virginia. But even the locals seemed determined to ignore him. Late in his second season with the Squires I worked as the talking head for a CBS-TV feature on Erving. For our intro, we took a camera onto the sidewalks along the main drag in Norfolk and asked passersby if they knew who Julius Erving was. "The mayor," said one respondent confidently. The governor, said another. The admiral in charge of the local naval base. A heavyweight in the local Jewish community, said one guy, trying to find a clue in Erving's name. "I don't know," finished first in the poll. Basketball player got no votes at all.

Dr. J began to emerge from obscurity the next season, when he was traded to the New York Nets. And that, at last, began to put an end to the era when Julius Erving was the best basketball player no one had ever heard of.

Commenti

Posta un commento