Too much, too young? Stephen Roche on success, fame and money aged 21

January 21st, 2021

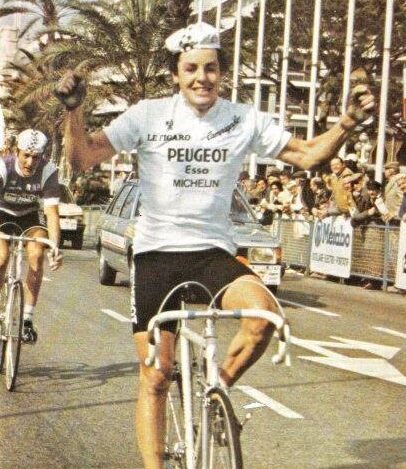

Stephen Roche wins Paris-Nice in 1981 in his first weeks as a pro rider and aged just 21 years riding for the Peugeot team. Roche believes the new generation of riders now enjoying success can keep it going for years, despite those who doubt their longevity prospects. However, while riders were now looked after better than ever, Roche says the top level of the sport is now much more intense than in his day

The past couple of seasons, especially last year’s Covid19-hit campaign, have witnessed so many very young riders break through to the top tier of the sport that something of a generational change has taken place.

The changing of the guard, and the sheer scale of the success achieved by the new wave of riders, has seen a debate emerge about whether those already at or near the top of pro cycling in their very early 20s will be able to keep it going.

Stephen Roche was himself an instant star on the pro scene aged just 21 years back in the day. He believes the likes of Mathieu van der Poel (25) and Wout van Aert (26) – both doing huge racing and training volume year-round – and even younger stars like Tadej Pogačar (22), Remco Evenepoel (20) and March Hirschi (22) can silence the longevity doubters in the years ahead.

But Dubliner Roche added pro cycling was now more pressurised than ever and required a full-on effort – all year, every year; something he says did not apply during his career.

Marc Hirschi, Tadej Pogačar, Remco Evenepoel and Filippo Ganna, four of the new generation who have ripped it up in pro cycling in the last two years. Stephen Roche says they can keep it going, but they must be careful

Roche, now aged 61 years and living in France, told stickybottle that any young rider winning big now in the first couple of years of their careers faced extreme mental and physical demands if they wanted to continue in that vein into, and even beyond, their mid 30s.

“When I see these riders, and there are so many of them now who are just 20 or 21 years old; when I see them in interviews in the media what really strikes me is the passion they have, not just for racing but for cycling,” he said.

“I think most of them are the types who’d be getting out on the bike even if they weren’t racing. They seem to love cycling and, for me, that’s really important if they want to keep their careers going for many years.”

Van der Poel (25) and Van Aert (26) have been pros for much longer than the last couple of seasons, but they have become two of the biggest names in the peloton in the last two years.

And during that very short period it seems a whole generation of even younger riders has followed very quickly in their wake.

Stephen Roche leads Sean Kelly in the early days at Paris Nice.

Roche said in the first years of his and Kelly’s careers the media interest at home was modest. In contrast, there was now intense daily coverage, especially online, documenting the new generation of young stars

(Photo: Cor Vos)

Those younger men have all come from the U23 or even junior ranks in the last few seasons, yet they are already among the biggest names in pro cycling or are, at least, well on their way.

They include Tadej Pogačar (22), Quinn Simmons (19), Sergio Higuita (23), Filippo Ganna (24), Marc Hirschi (22), Tom Pidcock (21), Jai Hindley (24), João Almeida (22), Egan Bernal (23), Remco Evenepoel (20), Ivan Sosa (23), Pavel Sivakov (23), Aleksandr Vlasov (24), Fabio Jakobsen (24), David Gaudu (24) and Lennard Kämna (24), among others.

Many have questioned if riders who become stars so young can sustain their careers as long as those who develop later, especially in the modern era when many pros are continuing to race past 35 years old and some until they are very nearly 40 years old.

Roche said the current young crop can survive in the pro peloton as long as anyone and that achieving success so young does not have to change that. But he said their careers may also ebb and flow.

It is a mark of just how young the new breakthrough riders are that Egan Bernal, who only turned 24 years old last week, is often not included in stories discussing the new generation

Roche said lots of spectacular wins may not come every year for the new generation, something they will need to be able to handle. At the same time, a fallow season or two may be followed by another run of major victories, with Roche citing Philippe Gilbert’s career trajectory as an example of that.

“I think it is hard to stay at that top level for years and years and it’s only the odd exceptional rider, like Gilbert, who could do that,” he said.

“For a start, the mental aspect to it is very hard, as is the physical side. With the young guys who are 20, 21, 22 years of age, they are already doing everything (to expertly prepare for racing) that they can; their diet, body fat, their training. It’s all in place for them.

“And that’s putting a lot of pressure on them because even in the winter time they can’t shut down the way we would have been able to shut down.”

Fresh off the boat from Ireland: Stephen Roche at the very start of his pro career, when he took big wins just a few weeks into his tenure with the Peugeot team

Roche added long gone are the days of a lengthy break in winter followed by a gradual return to training and then treating the early part of the season as further training. His generation of riders could completely switch off from cycling mentally for a prolonged period in winter, he explained. But the current crop of young talent did not enjoy that same luxury; something Roche felt may undermine the longevity of their careers.

“The riders today are taking their bikes on holidays with them because they don’t want to lose too much of the condition they achieved for themselves in the previous year. So it’s a 365-day a year job now whereas in our day you’d have gotten away with taking a month out.

“Even family-wise… OK it was difficult in our day. But I think it’s more difficult for the riders now; maybe not for the classics guys but certainly for the Grand Tour riders. They have to do so many training camps, they are away from home a lot. We maybe would have done a camp before the Dauphine and the Tour de France. But today it would be common to do three-week training camps.

“So maybe these young riders can’t have a really long career? Or maybe it can be really long, but not all at that really high level because after a while something has to give; whether it’s tendons, ligaments, the impact of crashes.

“The margin between winning and not winning is also very narrow now and these guys always have to be so finely tuned all the time. And if they’re not, there’s always somebody else coming to take your place. So they always have to be switched on.”

Philippe Gilbert is still going strong aged 38 and with a contract with WorldTour team Lotto-Soudal that will carry him past his 40th birthday. Roche said pros who lasted as long in the peloton as Gilbert were exceptional

Roche said crash injuries appeared to be more severe today than they were in the past, with pelvic and back fractures more common, perhaps because the riders were thinner or the speed in races was higher.

Roche threw his lot in with the Peugeot team in 1981; turning pro after a couple of seasons winning all around him in France with the ACBB amateur team, including victory in Paris-Roubaix Espoirs at the first time of asking racing on the cobbles.

In his first six weeks as a pro, and though he was just 21 years old at the time, Roche beat Bernard Hinault, then a two-time Tour de France winner, for overall victory in Tour de Corsica stage race and followed that up by winning Paris-Nice overall. He also collected a stage win in each of those races on the way to overall success; winning the Col d’Èze TT stage in Paris-Nice.

It meant just weeks after first pinning on a number in a professional race he was a big star. He said it wasn’t something that went to his head, nor did he feel pressure or expectations because of it.

Instead, he said he was insulated from those pitfalls because his mind was always constantly fixed on his next race; something he believed was exactly the same for the successful young riders of today.

Roche and Kelly in the very early days. While both enjoyed success young and were marked out for big things from their teenage years, the slower pace of the media meant they could focus on their performances for years before becoming public property

“I never got carried away,” Roche said of winning big in his first season as a professional in 1981. “For me, winning was the fruit of the work I’d put into it and you always had a sense of moving on to the next race. Looking back on it now today, probably one of my regrets is not taking a bit of time to savour the big days at the time.

“For me it was always ‘get on with it, get on with, get on with it’. I think when you compare back then to today’s racing scene, a good few things have changed.

“For a start, I didn’t have much money back in those early days. And one thing you could be sure of was that the more you won, the more money you got. Some of the top guys of today, even if they are those really young guys, they are getting very, very good salaries. So in that sense, financially, we were probably hungrier.

“At the same time, the commitment from the young riders of today is absolutely huge. During our time, our lifestyles were totally different, maybe a bit haphazard, even with our training. We trained and then we raced. Now the riders have coaches, dieticians, psychologists, managers and they also have so much media around them too, and social media.

“In our generation, nobody really hit very, very good form until they were, say, 23 or 24 years of age. Then you were at a peak from about 24 to 30, when you started going downhill; maybe still winning now and again, but not so much.

“We also would have raced on 100 or 110 days per year, whereas today some of them are riding 60 or 70 days in a year. Today they may be still doing the same amount of kilometres per year as we were doing, but they are doing a lot more of that at training camps.

“We were always afraid to miss racing and go to a training camp instead in case we’d lose form. We always felt we needed to keep our finger in the pie, so to speak. But today with the more scientific approach, they all know exactly where they are with training because it’s all in their numbers.”

Evenepoel’s rise has been the most rapid, winning big races straight out of the juniors including the European TT title. But every move he makes is covered intensely by the media, something Stephen Roche says the young riders must adapt to and that wasn’t a feature for him when he was breaking through in the early 1980s

Roche said top flight teams were much larger today, with more staff and more expertise in every area of performance. However, while that huge increase in resources around riders was advantageous, it also added to the pressure to perform on the bike.

He also saw the media, and the hype it could create so quickly around very young riders, as a pressure he never had to deal with. While somebody like Remco Evenepoel was a national figure in Belgium and everything he did was covered daily in the media, especially websites, the news cycle was slower in the pre-internet days.

Roche added that for him and Sean Kelly in the early days of their career, Jim McArdle of The Irish Times was the only person who covered them regularly in the media. It wasn’t until around 1985, by which time he and Kelly were well established and very experienced, that any significant form of media coverage began, he said.

That coverage built up for a couple of years before going into overdrive from 1987. And because of that, Roche said, there was no media-generated pressure during the first years of his career.

Roche insisted it was important for the young successful riders of today not to take media coverage to heart and to try and accept that a media story was simply the perspective of the person who wrote it.

“But of course now there are so many bloggers, so many people writing online. And that can’t be easy for the guys today. Having said that, cycling can’t all be fot money or for media coverage. And I really do think these young guys have a great passion for the sport.

“So even though many of the successful riders now are so young and they’re going to earn a lot of money; the passion is there. Of course it will get hard when they see young guys coming up behind them and that’s when you’ll see the real champions; those guys who can bounce back.”

Where did the name come from?

A stickybottle, put simply, is the knackered cyclist’s best friend. As a rider is being dropped from a group, the team manager or support worker in a following car holds a bottle out the window to hand it up. As the handover is taking place, the rider grabs the bottle tight, as does whoever is handing it up, enabling the rider get a good tow and push from momentum of the car. It’s known as a stickybottle because it appears neither the rider nor the person handing it up is able to take their hand off the bottle; it looks stuck to their hands. But please don’t try this at home. We’ve been slyly cheating this way all our lives; it takes a while to perfect.

Commenti

Posta un commento