PRETTY DAMNED MARVELLOUS

The Dutch PDM team were trendsetters in the 1980s, and came close to winning the Tour on several occasions, but always just came up short. Procycling looks at their short but influential time in sport

Writer William Fotheringham

Team Association should be a game all cycling fans play. Name a team. Then say whatever first comes into mind. La Vie Claire: kit. Festina: doping. US Postal Service: Lance Armstrong. ONCE: Alex Zülle's spectacles. Molten: Merckx. Sky: the line (and where you draw it). And... PSM: bus.

Nowadays, every team has a bus, even outside the World Tour. The vehicle is integral to professional cycling, so much so that when Team Sky were in the pre-launch phase, the design of the bus was a real topic of conversations. The 'Death Star', as David Millar once dubbed it, was an integral part of the iconography and ethos of the team and how they wanted to project themselves.

But team buses haven't been around for that long. The team bus as we know it began with PDM in the late 1980s. Cyrille Guimard's team did have one, earlier in the decade, but it sticks in no one's mind. The big black behemoth with the tinted windows was where the Dutch team truly made their mark. In 1989, other teams still had camper vans; in 1991 you could still interview a bike rider sitting on the bonnet of a team car with nowhere to hide before a race began. PDM were different.

Take a May 1989 interview from Winning magazine where (Australian) writer Rupert Guinness travelled with Sean Kelly and PDM to Milan-San Remo. "PDM chauffeur Rob van Der Merwe proudly captained his glossy black Mercedes passenger bus through Northern Italy, from the Adriatic coast to the industrial capital of Milan," wrote Guinness. "For Kelly, bus travel like this was a new experience in his 13-year career, one he confesses he was a touch reluctant about before finally signing up with PDM."

"I wasn't too keen about traveling by bus before. But this is different... there's more space," Kelly told Guinness as he "lounged back, legs outstretched".

Kelly added: "There is a shower on board, beds, and cooking equipment. There's even a video machine and TV which is perfect if you are waiting to do a time trial. You can watch what gear the riders before you are using, see how they are being affected by the wind."

Thirty years later, Kelly still remembers the bus, which was a huge advance on anything he'd experienced at KAS, his previous team. "It was impressive, big and black, leather seats inside," he says. "For me, it was a huge difference because at KAS we didn't even have a camper, just cars. The mechanics truck was really impressive too: huge, with a massive number of bikes and spares." Welcome to the new world. The PDM bus was more luxurious for the riders and a good way of keeping pesky journalists at bay. And it wasn't just a way of getting riders from A to B. It was a marketing too: an advertising hoarding for the team sponsors' logos, and a way of making clear that the team was moving with the times.

The PDM bus was also the visible tip of an iceberg of improved rider support as the sport transitioned from the low-key, low-budget affair it had been in the early 1980s into the big-budget monster it had become by the mid-1990s. "KAS were well organized," says Kelly. "But PDM were a step ahead, maybe two steps. Just the whole set-up, the look of it, the buses, cars and so on. They had a whole staff of logistics people. You'd be notified by fax a week or 10 days before the races. At other teams it would be a phone call. If you were going by bus, it would be a fax giving the pick-up point. And they had the race bikes at the truck, so you wouldn't have to fly with your bike, which I had to before."

--------

By 1989, when Kelly gave Guinness his interview, PDM had pretty much reached they apogee. The Irishman, ranked number one in the world, had come over from KAS with his sidekick Martin Earley. Steven Rooks and Gert-Jan Theunisse, the team's two-pronged climbing strike force, were at their best: in 1988 Rooks had won the mountains classification and stage 12 of the Tour de France at Alpe d'Huez, and they had added classic wins with Adrie van Der Poel at Liège-Bastogne-Liège, Rooks at the Championship of Zurich and Theunisse at San Sebastián. PDM headed thew FICP team rankings.

To understand where PDM fitted in, we need some context. The mid to late 1980s were the zenith of pro cycling in the Netherlands. At the start of the decade, long-standing champion Joop Zoetemelk had become the second Dutchman to win the Tour de France, riding for the all-conquering TI-Raleigh team, which hovered up everything with riders like Jan Raas, Gerrie Knetemann and Ludo Peters.

In 1984, TI-Raleigh changed shape and split; given the stature of the names that its boss Peter Post had recruited over the years, all the Dutch teams that followed would have links back to that squad. In 1984, Post landed vast Japanese corporation Panasonic as new title sponsor, switched to Eddy Merckx bikes, and at the same time, Raas left to run his own new team backed by home-goods supermarket, Kwantum-Hallen.

Raas's team moved from one big sponsor to another: retail chain Superconfex, low alcohol beer Buckler, software giant WordPerfect, Rabobank... and it still exists now in the form of Jumbo-Visma. In the wake of the schism between Raas and Post, two more teams emerged: in 1988, a small squad backed by vehicle insurance company Transvemij - whose logo is still to be seen on trucks crossing Europe - hired Post's former enforcer Cees Priem and expanded to become known as TVM. PDM's firs directeur sportif was Roy Schuiten, a mainstay of Post's TI-Raleigh through the 70s. The Netherlands might be small, but it had four major teams by 1989: Panasonic, Superconfex, PDM and TVM.

Each of quartet of teams could be defined in a different way, linked to the former riders who ran them. Panasonic were Post's team. Full stop. The former King of the Six Days was a hard nut with a vision of racing which gave him dominance around the turn of the decade, but became increasingly outdated as the 80s progressed, and his teams consequently declined. Kwantum and its successors built on the Post model: multi-faceted, stylish. In the 80s at least, they were defined by a feud with Post's teams that verged on the ridiculous.

Under the shouty, jovial Priem, TVM were the jokers in the pack, the mavericks who hired riders with long hair in ponytails - Robert Millar and Phil Anderson - who were led by men who were inconsistent at best - Dimitri Konychev and Jesper Skinny - and who were organizationally a shambles, with bikes that weren't to standard and team cars where maps and timetables were unknown. They got lost even in Holland, Millar once recalled.

PDM were somewhere in the middle. According to Kelly, the intra-Dutch rivalry mattered as much to their managers - Piet van Kruijs and Jan Gisbers - even though it wasn't as bitter as the Raes-Post vendetta. "Before the classics, they would tell u, if Panasonic have a rider in the break, we need one, if they have two, we need two. It would be the same at Kwantum, but if they both have riders there, then 100 per cent we have to be there too."

--------

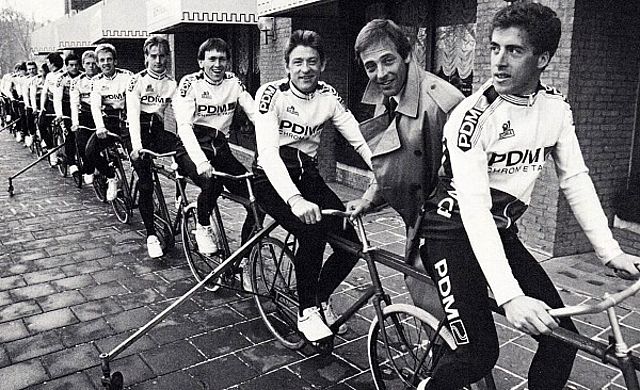

The PDM team was founded in 1986 as a partnership between Manfred Krikke, the manager of a company called Rentmeester, which distributed Concorde frames and Ultima clothing, and a PR man called Harrie Jansen, on of the ultimate fixers in world cycling in the late 80s. The Concorde-Ultima connection was crucial for the 'look' PDM developed, because Krikke was able to work seamlessly with both companies. "Hard but fair; above board when it came to negotiation," recalls Kelly.

The sponsor was a joint venture between Philips and Du Post to produce magnetic video cassette tapes. Now obsolete, the video tape was a big thing at the time, and the tapes were handed out from the team bus as it drove ahead of the Tour. That international angle explains why although the team were Dutch in their foundations, they always included a foreign rider among their leaders. And here too they were ahead of the curve: being a Dutch team, the lingua franca among riders and staff was English, the Dutch's second language.

The 1986 squad was fronted by the defending Vuelta champion Pedro Delgado, and co-sponsored by the MG gin company when it raced in Spain. The Dutch riders included Wim Arras, a prolific but now forgotten sprinter, the late Gerrie Knetemann, one of Post's stalwarts, and Rooks, who delivered wins in the Tour of Andalucia, the GP Wallonia, and crucially for a new Dutch team, the Amstel Gold Race. Rooks was joined in 1987 by Gert-Jan Theunisse, his close friend and former team-mate at Panasonic. The pair formed what amounted to a team within PDM, sharing rooms and a love of climbing mountains.

1987 saw Delgado involved in a memorable battle with Stephen Roche at the Tour de France, finishing second tafter holding the lead to the final Tim trial. In an anarchic race, the Spaniard suffered from the weakness of his team, who lost him 41 seconds in the team trial - his final margin of defeat was 40 seconds - and were never in a position to help in the mountains. At the end of 1987, the Spaniard returned to Reynolds and he was replaced by Greg LeMond, on the comeback trai alerter coming close to death in a shooting accident at the start of 1987.

PDM paid LeMond a basic salary of $350,000, with win bonuses that were never cashed in as the American struggled in 1988. LeMond liked PDM, however. "It's a classy organisation, calm, no pressure," he told writer Sam Abt that spring. "But they get their message through. They know the raiders know how to do their job. So many managers in cycling feel like they have to tell you how to eat, how you have to go to bed, how you have to get top in the morning, how you have to train."

The Dutch team did field an American in the 1988 Tour, but it was the unsung Andy Bishop, who had come into the squad on LeMond's recommendation. Without LeMond, Rooks and Theunisse came into their own, with Rooks taking the Alpe d'Huez stage for the seventh Dutch victory in 13 years on the top of an ascent described at the time as "the most southerly village in the Netherlands". Rooks would finish second behind Delgado; the team's race was marred by the first of a series of positive testosterone tests for Theunisse, who was docked 10 minutes and lost his fourth place. LeMond's departure one year into a two-year contract opened the way for the arrival of Kelly in 1989 after the collapse of KAS following the death of the Spanish drinks company's head. "Kind of a rushed deal," recalled Kelly, who knew he was heading for a different kind of team after almost a decade as sole leader of Jean de Gribaldy's various teams. "I knew before I went, there were other big names. It worked out well, but got a bit heated at times over who was actually the leader."

At PDM it didn't all hinge on the Irishman, but that didn't make life easier all the time. At Milan-San Remo that spring, his team mates piled on the pressure on the approach to the Cipressa with the new signing Raul Alcala, Rooks and the Belgian Rudy Dhaenens, only for eventual winner Laurent Fignon to elude them before they reached the Poggio.

When Liège-Bastogne-Liège came round that year, Kelly realized he had to race differently. "I had a stomach problem at Tirreno and suffered in the cobbled classics. By Liège-Bastogne-Liège I was getting better. But they already had Rooks and Theunisse for that kind of race. I worked out my own tactic of getting away early, so I would be up the road and they would have to control it behind."

Kelly escaped with Phil Anderson, Pedro Delgado and Fabrice Philipot, and duly won the sprint after a nail-biting chase into Liège-Bastogne-Liège. The crucial point, however, is that he had to pre-empt his fellow leaders so that they would work for him; he had figured that out beforehand, and he made sure to keep it to himself. "I wasn't riding against them, but I was putting myself in the best situation possible. The team were happy but I'm not sure when they went home that everyone wasn't thinking the Irishman had it worked out better than we did."

At that year's Tour, Rooks and Theunisse worked their mountains double act again, with Theunisse winning at Alpe d'Huez after a long solo raid - "the ultimate victory" as the long-haired Dutchman described it - and Kelly took the green jersey while Theunisse took the mountains. That year, and on occasion in 1990, the strength of PDM's climbers meant that when Kelly did get into the front group on the mountain stages, he was often the one who had to drop back to the team car to deliver bottles.

The 1989 Tour will always be seen as emblematic of PDM as a team - both impressive and dominant, yet nowhere near actually winning. They won the polka dot jersey with Theunisse, the green and red jerseys with Kelly and the combination jersey with Rooks, and managed the impressive feat of stacking the top 10 with four different riders, yet at the same time not a single one made the podium. Riding with four leaders and five domestiques was a sub-optimal strategy, and the quartet looked to be racing each other as much as their rivals.

In 1990, Rooks and Theunisse moved to Panasonic, where Theunisse continued notching up doping positives that would see him serve a ban, and the 'Dutch twins' began the slide into obscurity. But at that year's Tour, PDM riders Raúl Alcalá and Erik Breukink provided the fireworks, winning all three time trial stages, with Breukink finishing third overall. The Dutchman had looked good enough to win, but one off day, at Luz Ardiden, cost him dearly. By now, the team had invested in the East German sprinter Uwe Raab, who won the points prize at the Vuelta. Kelly, meanwhile, added the Tour of Switzerland, although his classics season went west due to injury.

1991 shaped up well initially, with Jean-Paul van Poppel winning four stages in the vuelta and Breukink taking the DuPont Tour in the US. But the year - and the PDM story - ran aground in that year's Tour, where the entire team had to withdraw in the opening week due illness linked to a contaminated glucose drip.

It was an almost unprecedented event at the Tour for a whole team to pull out, and it was summed up by Stephen Bierley's line in the Guardian: for PDM read Pretty Damn Miserable. Kelly recouped something for the team with two of his finest wins, in the Nissan Classic and the Tour of Lombardy, but he was on his way out and so were PDM, although they would limp on through 1992.

In the end, PDM got two second places, a third and a fourth at the Tour, but never won it. They will be remembered for their wins and results over a few short years at the end of the 1980s, but the metaphorical odour of that dodgy drip lingers, however, and so does the image of that big black bus.

TEAM PDM MAJOR WINS

YEAR RACE WINNER

1986 Amstel Gold Race Steven Rooks

Tour of Holland Gerrie Knetemann

Tour de France, stage Pedro Delgado

1987 Paris-Tours Adrie van der Poel

Tour de France, stage Pedro Delgado

1988 Liège-Bastogne-Liège Adrie van der Poel

Tour de France, stage Steven Rooks

Clásica San Sebastián Gert-Jan Theunisse

Zurich Championship Steven Rooks

1989 Liège-Bastogne-Liège Sean Kelly

Tour de France, stage Gert-Jan Theunisse

World Cup Sean Kelly

1990 Tour de Suisse Sean Kelly

World Champs RR Rudy Dhaenens

1991 Tour de France, stage Jean-Paul van Poppel

GP Eddy Merckx Erik Breukink

Giro di Lombardia Sean Kelly

1992 Tour de France, stage Jean-Paul van Poppel

Clásica San Sebastián Raúl Alcalá

Commenti

Posta un commento