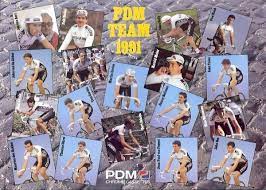

TDF 1991: Cycling’s unknown scandal; PDM are out of the Tour

The 15 July 1991 was a watershed moment in 90s cycling. If the truth of the eras dark underbelly didn’t reveal itself until the 1998 Tour, then the first warning signs reared its head that day in Brittany. As the riders began to gather in Rennes ahead of a 207.5km ride west to Quimper, the big story according to Phil Liggett was that overnight the PDM team had contracted a virus that was spreading throughout the team.

Uwe Raab and Nico Verhoven failed to take the start and during the stage both Martin Earley and Jean-Paul van Poppel abandoned, before Falk Boden fell behind and came in 37 minutes down and outside the time-limit. In one day, the PDM team had lost five of nine riders.

In commentary, Paul Sherwen reckoned it was something in the food given how fast it hit them, and being seven years shy of the Festina affair, we had to assume that was true. Of course, the obvious question as to why most of the non-riding staff were still healthy did not appear to be asked.

Up front the stage went on and Erik Breukink for the time being held onto the peloton for the day. Thierry Laurent went up the road alone for 64km before being brought back. After the final intermediate sprint, Claudio Chiappucci attempted an attack but was marked by Greg LeMond and Gianni Bugno. The Italian already going on the offensive after the time lost in the time-trial. With 29km to go, a four man group of Brian Holm, Michel Dernies, Nico Emonds and Phil Anderson went clear. They never built a big lead, but they got enough of a lead. It is amazing how often a break could hold off a peloton in the early 90s. And of the four it was the Australian, Anderson, a previous two-time top-five finisher at the Tour, who won the sprint. It was his first win on the Tour since his first way back in 1982.

A few days ago, Sean Kelly had been looking for his first win since 1982 also, so Anderson had shaken off his long wait first. But Kelly now faced a world of other issues, for as a member of the PDM team, he too was feeling ill. And that night, Kelly, along with the other three surviving members of the squad, Raúl Alcalá, Jos van Aert, and Breukink, in third place overall, abandoned the Tour. It was a remarkable development when news filtered though the race the next morning. In twenty-four hours, the entire PDM team were gone from the race.

But what was being filed away as a viral outbreak, influenza, salmonella or some other food poisoning, that left team manager, Jan Gisbers claiming the effects of too, was all nonsense. Something far more sinister was gong on. Those inside the sport may well have known it then, but it took several years before the truth began to come out for the public.

But even by 1991, PDM were well known throughout the sport for their drug use. PDM stood for Philips Dupont Magnetics, but the English nickname soon became Pills, Drugs and Medicine. In French it was “Plein de Manipulations de Dopage”. Speaking in 1997, team owner, Manfred Krikke said that, “When we started PDM we decided that we would not be the most ethical team in the peloton. The one rule imposed from the PDM directors was that there was to be ‘no drug affairs’ rather than ‘no drug taking’”.

As far back as 1988 the team had been linked to drug use. An entry in team doctor Bertus Fok’s diary for 11 July 1988, said that Steven Rooks, Gert-Jan Theunisse and Jorg Muller had all received blood bags on top of the usual testosterone and cortisone. Three days later on the stage to Alpe d’Huez, Rooks and Theunisse finished first and second. Following that was the second individual time-trial where Perico "Pedro" Delgado, a former PDM rider, secured his Tour victory, and tested positive for probenecid. That same day, Theunisse failed a test for testosterone.

And things continued from there. For 1991, PDM team owner, Manfred Krikke brought Wim Sanders into the team as team doctor. A week before the 1991 Tour, during the Dutch national championships, Breukink had a bad day due to a lack of fuel. There and then, Sanders and Gisbers decided to administer Intralipid to the team at the Tour. A fat emulsion medicine used to help riders with feeding problems during the race.

Yet it needs to be administrated right, and that is where they went wrong at the Tour. During a TV documentary in 2008, Sanders said that the cause of the illness in 1991 was careless storage of the Intralipid.

But the full truth remains unknown. Many believe there was more to it than Intralipid alone. Blood transfusions had been in sport for a long time by then and EPO was on the rise. Both can lead to adverse affects if stored and administrated wrong and many believe one of those to be a big factor with what went wrong with PDM that week.

There had been rumours of EPO in sport as far back as 1988 with Dutch and Italian doctors leading the way, but by 1991 it had became the cost effective go-to alternative to blood transfusions and more riders were getting in on it. It boosted oxygen carrying red blood cells and transformed a riders abilities. But in those early days at the turn of the decade, the drug came with considerable risk of misuse. In 1998, Dutch rider, Bert Oosterbosch, and in 1999 his compatriot, Johannes Draaijer, died of heart attacks under mysterious circumstances that have often been linked to EPO misuse. Those who could afford it, worked with the pioneering doctors, like Francesco Conconi, Luigi Cecchini, and Michele Ferrari, who later worked with Lance Armstrong.

Some of the riders to work closest with the three Italian doctors in those early days included, Tony Rominger and Gianni Bugno of Chateau D’Ax, and Claudio Chiappucci of Carrera. Miguel Indurain and his Banesto team were also rumoured to have worked with Conconi. All four seen a huge swing in their results around this time. Yet the drug was far from perfected and the benefits yet to be be exploited to the full. It meant that while there was a surge in improvement among those with access to the drug around 1989-1990, you could still win without it. The likes of Edwig Van Hooydonck, Gilles Delion and Greg LeMond are testament to that.

But by 1991 the riders and their doctors were starting to maximise the drug and more taking the new magic potion. It may seem convenient that LeMond would later cite 1991 as the year he felt EPO came into the peloton, but he has a point when you look at what happened to him, who was beating him, and where the racing went in the years after. By the age of 30, LeMond, a three-time Tour winner and consistent challenger, was all but finished. Likewise Laurent Fignon later told of how riders who used to be in the gruppetto over the high mountains, were soon leaving him behind.

And as more sponsorship money came into the sport in the years that followed, there was greater demand for bigger results, and teams turned more and more to EPO. In 1993 the French got onboard via the infamous Festina team, and in 1994 the Gewiss-Ballan team finished first-second-third at Flèche Wallonne in an astonishing performance linked to the perfection of EPO. The team doctor was Michele Ferrari and after the race he said, “EPO is not dangerous, it’s the abuse that is. It’s also dangerous to drink 10 litres of orange juice”.

By 1995 there were few left in the peloton not on the drug and it was all but impossible to win clean. It would be a further three years before the door was opened to the public. Yet it far from levelled the playing field as the drug worked better for some than others. It only muddied the waters to such an extent that those who benefited from the advantage before even got left behind. Chiappucci and Bugno faded and in 1996, Bjarne Riis dethroned Indurain and won the Tour. Riis whom Phil Liggett once mused during the 1990 Tour, while he was in a break, that the big-man might struggle to get over the mountains, would finish the 1991 Tour 107th, 2 hours 8 minutes behind the winner. Later nicknamed ‘Mr 60%’ for his enormous hematocrit level (red blood cell count) thanks to excessive EPO use, Riis first tried the drug in 1993 and that year finished the Tour 5th. The transformation it caused was undeniable.

So why then would a team like PDM, whose management admitted they never intended to be the most ethical team, from a country mixed up in the drug from its earliest days, not be involved? Johannes Draaijer, who died in 1990, rode for the team. Two other riders the same year had to stop racing due to heart defects. Could misuse in the days when misuse was common, explain what happened that evening in Rennes? A botched administration of the Intralipid could be all it was, albeit still illegal, or maybe it was a mix of the pair. Whatever it was, one thing is certain, this wasn’t a virus and it wasn’t food poisoning.

Whether the incident scared someone like Breukink clean, or at least to take less extreme risks, I am not sure, but one thing is clear, he was never this good again. Abandoning the race as LeMond’s nearest rival, having finished third the year before, the Dutchman would finish 7th in 1992 aged 28, but in his subsequent five entries he wouldn’t place better than 20th. He still had good results in smaller races and remained good in the time-trial but retired after the 1997 season.

There are others like this too. Raúl Alcalá, so brilliant in that time-trial in 1990 and who looked a genuine favourite to win the race for a bit, finished only three more Tours, in 21st, 27th and 70th. He retired from professional cycling after the 1994 season aged only 30. That said, Alcalá remains one of the best riders to come out of Mexico and in 2010, aged 46, he won the Mexican national time-trial championship.

For all the retrospective talk of 1991 being a year that seen a shift to the worst for drugs in the sport, this was also an era of change all round for the sport. Watch a race from 1985-1989 and it looks a world away from 2020. Watch a race from 1995-1996 and it feels a lot closer to today than it is. The early 90s brought about these changes. From aero bars to race radios to heart rate monitors to shifting gears on the handlebars instead of the down-tube, and clip-in pedals opposed to toe-clips, the sport was entering a new era. Here in 1991 most riders still reached for the top tube to shift gears while unfastening the strap over their feet to put a foot down after a stage, but times were changing.

Greg LeMond was always a forerunner of technology. Always looking for that legal advantage that could help him out on the road. In 1989 he turned up to the final time-trial with a set of aero bars and in turn overhauled Laurent Fignon to win the Tour by 8 seconds. Now, two years on, LeMond was spotted wearing a headset that allowed him to communicate with the team-car behind. He had been testing it out throughout the race so far, but opted to go without the distraction in the time-trial. Still, as LeMond does, the sport tends to follow. One year after revealing his time-trial bars, half the field had them. By 1991, few went without. And the consensus was that within a year or two, all the team leaders would be kitted out with radios.

Last year also seen a rise in heart rate monitors among riders. The ability to measure their internal engine and assist them on knowing when they were near their limit. Many riders still go without, preferring to ride on feel than have the distraction of the digital readout on their handlebars, but you could sense this technological change coming too.

Indeed, 1991 was a real watershed year. Not only for the dark changes and the changes in technology mentioned above, but the era of leadership in the sport was due to shift in the days ahead as they hit the high mountains and it wouldn’t be the same again once they came out the other side.

But on Tuesday, 16 July, as the race went 246 km south-east along the Bay of Biscay coast, the sport had notched up its first drugs scandal of the new decade without even knowing it and Greg LeMond was in a better position than ever to win the Tour yet again.

The pace of the peloton was high from the gun. The stage would finish an hour and a quarter ahead of the fastest scheduled finish at 47.2 km/h. Perhaps with the rest day in mind, or perhaps to get away from the stench of what had gone wrong at PDM. As such few attacks got far. Rolf Jaermann bridged across to a break that had gone clear with 43km to go before striking out alone with 20km left. Riding his first Tour, and having led the King of the Mountains competition for the first three stages, he held off the bunch until the final 2km before being caught. It only served to give false hope to the sprint teams that their job was done, but as they went under the red kite, Charly Mottet took a flier and held off the sprinters who hit the line a length behind him. Yet again their day spoiled by the late bid for glory. The win was the first for the French by a rider not named Thierry Marie at this years Tour.

Mottet had been a big hope for French cycling after finishing 4th in 1987 at the age of 24, and 6th in 1989. But in 1990 he had finished down in 49th and had been left hunting for a stage win as consolation. He got it with a solo attack on stage 15, at which time he announced he would no longer be going for the general classification at the Tour. Now in 1991 it felt like he was a man of his word. The win today still left him more than 8 minutes behind LeMond having lost 6 minutes in the time-trial alone.

The big story of this Tour so far had been the plight of PDM, and while it would live long in the memory, it was forgotten about in the short term as the mountains lay ahead of the one and only rest day and a flight down to the Pyrenees. The strongest team in the world was out of the race and LeMond had lost his biggest rival. Little now in the way of his fourth title then, or so we thought.

General Classification after stage 11:

1. Greg LeMond (Z) in 46h15’32”

2. Djamolodine Abdoujaparov (Carrera) +51”

3. Miguel Indurain (Banesto) +2’17”

4. Jean-Francois Bernard (Banesto) +3’11”

5. Gianni Bugno (Gatorade) +3’51”

6. Luc Leblanc (Castorama) +4’20”

Commenti

Posta un commento