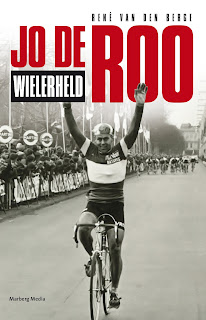

Jo De Roo - THE FLYING CLIMBING DUTCHMAN

The most successful rider to come out of the Netherlands prior to 1968 Tour de France winner Jan Janssen, Jo De Roo was the ultimate in all-rounders, capable of beating the very best on the plains of Paris-Tours and the hills of Lombardy

Writer: Peter Cossins

ProCycling #208, October 2015

At 77, Jo De Roo’s blue eyes are as piercing as ever and he is still very trim. A slight limp initially suggests that age is getting the better of him but is in fact the result of recent knee surgery that is currently preventing him enjoying his usual two or three weekly sorties on his bike in his home region of Zeeland, hopping from one island to the next, just as the Tour de France did this summer. “It’s always windy and it’s pretty hard,” he says. It is ideal terrain, he adds, for a rider aiming to make a name for himself in the Classics.

Holland’s most successful rider until the emergence of Jan Janssen, De Roo was that rare beast who could win almost any of the Classics, no matter what the terrain. In his best year of 1962, he was victorious in Paris-Tours, the Giro di Lombardia and the immense one-day test that was Bordeaux-Paris. Those successes helped him claim the season-long Super Prestige Pernod International series, effectively making him the sport’s number one rider. In winning Paris-Tours he set what was then the fastest average speed for a Classic, his mark of 44.903 kph for the 267 km earning him the UCI’s Ruban Jaune (Yellow Riband) trophy. A fortnight later, he won Lombardia, the final edition in that period to feature the fearsome ascent of the Muro di Sormano.

“The fact that I won the fastest and the hilliest Classic shows how versatile I was as a rider,” says De Roo, the morning after being feted at the Ronde van Vlaanderen Museum as a past winner. “I think the key factor in me winning such different races was the simple fact that they were both long races and I tended to thrive in events like that. “Whereas most riders would get tired after 200km, I felt better the longer the race went on, and it didn’t matter whether we were racing on the flat in Paris-Tours or in the hills of Lombardy. I could also climb well – not on days when there were five high passes but the shorter climbs in Lombardy suited me. And of course I could also ride in the wind because I come from Zeeland. All in all, I had just enough of the talent required to win each of these Classics.”

The Dutchman admits he didn’t show much talent when he saw his first bike race “in 1947 or 1948” and felt intrigued enough to give it a go himself. “I felt a really strong pull towards the sport right away and started riding with my friends,” he recalls. “When I was 15 or 16, I got a licence as a novice racer. For the first few years of my career I didn’t win anything. I was always towards the back of the field and everyone kept telling me to quit, that I was no good. But it’s in my character to do the opposite of what everyone tells me, to see things as a challenge, so I kept on with it.”

His doggedness led to success in some amateur Classics in the late 1950s and then to his first professional contract with the Dutch Magneet-Vredestein team. Solid rather than stellar, he got his break in 1959 when he came to the attention of the French Helyett team led by Jacques Anquetil during the Tour de l’Ouest in Brittany. “At that time a few Dutch riders were contracted by French teams and they had performed well, so the DS at Helyett was looking for one, too. He was really after a sprinter but the mechanic told him he shouldn’t take just the sprinter, as he could well end up feeling isolated within a totally French team, so he took me as well,” De Roo explains.

“My first year was 1960 and my first race was the Tour of Sardinia, which I won and that really marked the start of my career. I went on to win seven Classics and two national titles.”

As well as Anquetil, that Helyett team also featured Jean Stablinski, Shay Elliott, André Darrigade (whox de Roo beat in a sprint to win the Manx Trophy on the Isle of Man in 1961) and Jean Forestier. “It was some team, definitely one of the strongest of that era, but I still managed to find my niche there in one-day races, which the likes of Anquetil weren’t always that interested in,” says De Roo. “I preferred one-day races, though, as I found it really hard to keep my focus during long stage races.”

The Dutchman insists he stood out in another way, too. “I was a bit different to other riders in my era. Most of them raced throughout the whole season but I didn’t do that. If I didn’t feel great or my form wasn’t good, I would stop racing for a while, stay at home and rest a bit, which is bit more like the programmes current pros have. People in Holland always used to say, ‘Jo, you should have won more.’ But I’m sure that if I had followed everyone else’s example and ridden more often, I wouldn’t have won all the great races that I did,” he points out.

Of his seven Classics wins, the one that stands out for De Roo is his first Lombardy success in 1962, primarily because of what he went through to achieve it and the prize that came at the end. The complicating factor was the Sormano, which wasn’t the beautifully surfaced artwork that the pros occasionally tackle in the current era. “The Sormano was introduced in 1960 because [race director] Vincenzo Torriani wanted to break the growing domination of the sprinters. Straight away it produced chaos in the race. Most of the riders had to walk up it,” he explains. “I rode it in 1962, which was the last time it appeared because of the scandal that blew up because Italian riders were pushed up the climb and foreign riders held back.

“That year I had a chance of winning the Super Prestige Pernod. I was lying fourth going into Lombardy behind Rik Van Looy, Walter Planckaert and a third Belgian rider, Emile Daems. I thought that if I rode well I could perhaps take third place and the decent prize that was on offer for that. When we got to the Sormano, I was starting to feel good and I passed the Italian rider Livio Trapè. But then I had a flat and had real problems getting going again because it was so steep. Due to the force I was putting through my pedals, my back wheel got jammed against the frame and I had to stop again. Soon after I got going the second time, I ended up with the straps from a lady’s handbag tangled around my handlebars and got pulled down. As I was getting up from that, Trapè went by with a group of Italian fans pushing him. Once I got over the top of the Sormano, I caught Trapè with 10km to go and went on to win, which helped me to win the Super Prestige. But I was furious rather than elated at the finish because of the way that the fans had behaved and what the Italians had been allowed to get away with.”

De Roo underlined his completeness as a rider when he repeated the Paris-Tours–Lombardy double the following season. At the height of his competitive powers, over the next three seasons he added back-to-back national road titles, three Tour de France stage wins and a crowd-silencing victory at the Ronde van Vlaanderen in 1965. He went clear on the Valkenberg with in-form Belgian champion Ward Sels. Knowing that his team-mate Sels was by far the quicker sprinter, Solo-Superia team leader Rik Van Looy neutralised all attempts to chase the leading pair. But on a rainswept, muddy day, local favourite Sels’ derailleur got jammed with Flemish mud, leaving him underpowered and easily beaten. It was only the second Dutch victory in De Ronde.

By the time De Roo rode the Tour de France for the fifth and final time in 1967, he was already contemplating life after cycling. He confesses that the death of his close friend Tom Simpson on that race crystalised the thought. The two men had got friendly when they shared a room during a month-long promotional tour to New Caledonia.

“In cycling, you don’t really have friends – you talk about the weather, you talk about women, you talk about the sport, you talk about fluffy stuff. But I had a special bond with Tom because our conversations went much further than that,” says the Dutchman. “At the start of that tragic stage from Marseille to Carpentras, our paths crossed in the toilets and Tom’s urine was green. I asked him why it was that colour – was it vitamins or something?”

De Roo describes how he rode with Simpson briefly on that sun-baked stage. “We were still a long way from the Ventoux on the flat and I said to him, ‘Take care of yourself today.’ He said, ‘Yes, of course.’ But Tom wasn’t like that. He couldn’t ride half-heartedly. It was all or nothing, and when he gave everything he went beyond his limits.”

Those blue eyes flash with even more intensity as he recalls the aftermath of his friend’s death. “I resent the fact that the story of Tom’s death is purely a story about doping. Yes, he was using amphetamines but we were all using them. I think he died as the result of a combination of things – extreme heat, because it was above 40 degrees, and because Tom started in the front group, then couldn’t follow but still went over his limit in trying to do so. Like I said, I resent the fact that it’s all doping, doping, doping, because a lot of it was down to his personality. I’m sure Tom didn’t take any more dope than the average rider, than we all did, otherwise we would all have died that day,” De Roo states.

“His reputation was as a rider who could give single-minded focus to an objective, as one of the best riders of the era. Although we were never team-mates, whenever we went to races in France we would travel together. I would go to his home in Gent and we’d set off together from there. His death was an awful moment but in the Tour life goes on. It’s sad but inevitable.”

De Roo retired at the end of the 1968 season and established a business selling luxury household goods. He admits he fell out of love with the sport for a good while but says he’s very happy that he did rediscover it in his post-racing years in his beloved Zeeland. Looking back, he’s especially proud of his unusual autumn double. Only three riders – Belgians Philippe Thys, Rik Van Looy and Philippe Gilbert – have achieved it besides him. And only De Roo has done it twice.

AN EYE ON ARU

As the Tour de France prepared for its first-ever stage finish on Zeeland’s polders, Jo De Roo was very much in demand for promotional events. For one, he rode the last 50km of the first stage to the Oosterscheldedam alongside former riders such as Cees Baal and Harm Ottenbros in order to raise money for the local authority to help cover the costs of bringing the Tour to Zeeland. But he also stuck to his regular viewing habits. “Next to the breakfast table at home I have the season’s calendar. When there’s a race on everyone else knows that I’ll be watching. If my grandchildren are there they know they have to be quiet when there’s racing on,” he says. “I like to watch Fabio Aru at the moment. When I won the Tour of Sardinia I beat Ignacio Aru, and now there’s another Aru from Sardinia. They’re not related but I still like that connection. But it’s not so much the riders as the tactics that I’m interested in. I like to see how the riders react to the conditions, both in terms of the race and the elements – how they’re dealing with the wind and so on.”

Commenti

Posta un commento