Patrick Sercu: The Phenomenon

“Eddy and I complemented each other. I was the speed, he was the strength and we were friends.” At home with sixties six-day superstar, Patrick Sercu.

Posted on12.02.19

Words: Graeme Fife

Patrick Sercu greets us by the open door into the lower floor of his condominium (he also has the upstairs apartment) and shows us into a spacious, light-filled room, the end wall panelled in glossy maple wood, a flat-screen television, family photographs. A balcony overlooks the garden; at the other end of the room are shelves lined with trophies, a dining table.

Photographer clicks his inbuilt light meter into action and sets off back to get the gear; Hasselblad will get the nod.

I sit on an armchair, Sercu on the settee. He remembers me from Bremen, when we spoke in French, and from a brief encounter at Ghent when he was so busy he had no time to say much more than hello in any language. Now we speak in English.

Where to start? Where Patrick Sercu started, here in Izegem, a few kilometres from where we sit, on the track built by Odile Defraye in 1912, the year he became the first Belgian to win the Tour de France. He’d bought a restaurant with his winnings and built the 166 metre cement track in the garden.

By 1959, when Sercu was 15 and ready to start riding, the surface was cracked and pitted. Albert repaired it and, in the photograph which shows his son riding it for the first time, the patches and ribbons of new cement grouting show white on the grey surface. His father organised a programme of competitions on the track for local teenagers.

“Did he teach you?” I ask. “He was my first trainer, my first promoter. I got on well with him. He’d finished racing, mostly on the road, but he did the Ghent, Antwerp and Brussels Sixes – I think he rode around sixteen altogether.”

Between 1964 and 1983, Sercu Junior rode 233 Sixes and won 88. But he also raced through the road season. His palmarès are quite simply dazzling. I ask how he managed a full winter programme as well as the long calendar of classics and stage races over what was an exceptionally long career.

He smiles. “I couldn’t stay at home. I felt a bicycle rider should always be in competition, on the track and the road. Maybe it was just how I was and I was lucky I could do it.” Moreover, by his own admission, he never took any more than two weeks off and even then only twice a year. The driving imperative for him at the time, as for everyone else, was money.

The Six-Days might have paid well in the ‘blue train’ – that élite cadre of some sixteen riders who star on the bill – but otherwise track racing delivered only slim pickings. When riders were paid very little on contract, earnings had to come from prize and appearance money. Reputation fuelled pay rises.

There was not the specialisation then as there is now. All riders faced a much longer season than today’s well paid pros. As an amateur, Sercu routinely raced on the track on Sunday and then on the road on Wednesday; kermesses through the summer, the hard, tight-cornered, cobbled local circuits where the intensity of the crowd’s enthusiasm both reflects and spikes the fury of the competition.

It must have been the experience of those short-lap town and village circuits which toughened him, early on, for the dizzy circling on the indoor wooden tracks.

Some riders new to track racing find the experience difficult to cope with and adapt to. It’s not only the hectic speed – which, on a small track like Ghent (166m), is exaggerated by the tightness of the bends – but the action of both centrifugal and g-forces on riders.

The centrifugal force hits just past the fulcrum of the bend and becomes a g-force, pushing the head down between the shoulders. Thus, a man giving his mate a sling on a corner will take a sudden punch of extra weight. As a result, on the bends, riders have to find the optimum line. A seasoned pro will accommodate himself to this after about an hour of riding a track and, if he keeps his line, a bend will throw him through the force. If not… added strain.

On a track like Ghent, with a tight radius of 11 metres, the imposed loading on a cyclist at speed is considerable. Assume a combined rider and bike weight of 90kg. The lap record is around eight seconds and at 18.18 m/sec, to begin exiting the curve on the 53 degree banking, a rider will generate a total centrifugal force of 275kg.

Deducting his 90kg he will have an imposed loading of 185kg pressing down on his shoulders and upper body. Add to this the effect on the nerves of racing at such close proximity to the rest of the bunch, the sudden swoops off the front by riders slinging in their partner or else swinging back down into the flowing stream, the sensation of a never-ending weave of cyclists at full lick…

Some riders, unacclimatised, have to peel off with nausea. Sean Kelly, an exceptional bike-handler and fearless sprinter, was solicited by many Six-Day organisers to ride the track but he refused – he found the prospect too daunting.

One of his contemporaries, Francis Castaing – a first-rank road man and well used to socking it out with the hard men of the bunch like Kelly, Jan Raas and Walter Planckaert – came to Dortmund to ride the Six with Alain Bondue, world champion pursuiter. Bondue, partnering the novice, was called, in the jargon, a taxi driver. Castaing lasted less than 15 minutes in the first chase and retired. Couldn’t hack it.

It was on the Ghent track that Sercu took his first Six victory, in 1965, partnered by Eddy Merckx. They’d met as teenagers at the Brussels Sportpaleis and become great friends. They both went to the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo, Sercu as Belgian sprint, omnium and Madison champion and both riders as newly-crowned world amateur champions: Sercu in the sprint, Merckx on the road.

Sercu took gold in Tokyo, dissension in the Belgian road squad robbing Merckx of a probable title. They both signed as professionals with Solo-Superia for their first engagements: the Sixes of Berlin, Brussels (they came second) and Ghent.

Ghent is Flemish Mecca, strictly Belgian hardcore. The Kuipke velodrome is like a lidded Wall of Death, the track exceedingly grubby with use, streaked with black tyre skid marks, grime, sweat. At the top of the banking, the boards dip and bump. Comfort is not catered to. The audience sits on crude wooden seating affixed to a bare concrete raked floor.

Walk round the undercroft and you see where the track boarding is exposed from below, a drumhead across which ripple the unbroken roll of the tyres inflated to rock-hard high pressure. The packed central oval is sunken well below the track so that one can see most of the action from here; the impression of speed is compelling, the thrill of it electric.

The area is flanked on the two longer sides by the cabins, constructed of simple partitions with a very narrow walkway between the bunks and the track barrier. The mechanics work on the inner side of the cabins with barely any space for much more than toolboxes. Wheels hang from projecting wooden poles.

In the early days, trapeze artists swung about overhead, a band on a dais pumped out polkas, marches and drinking songs, and the crowd did the drinking and the smoking. The fug of cigar smoke was often so thick, says Sercu, that you couldn’t see across from one side of the track to the other.

When I ask Sercu which of the Sixes he had most wanted to win, his reply is instant: “Ghent. It’s home.”

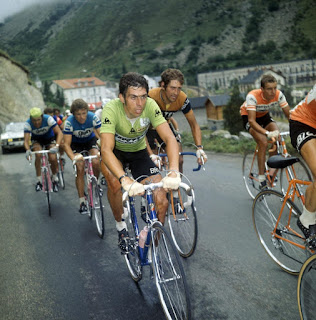

1966 World Cycling Championships. Patrick Sercu among the group of Dietrich Thurau, Bernardo Alfonsel and Pierre Raymond Villemiane.

I watch closely as he says this. There is the faint flicker of remembered pleasure, a hint of the zeal he displayed as a racer, but only beneath the reserve of a man who knows just how good he was. He has no need of vanity.

Like other outstanding cyclists to whom I have had the privilege to talk, he is almost matter of fact about his palmarès. He won Ghent 11 times, four times with Merckx and once as a taxi driver with Roger de Vlaeminck, another football nut whose winter pastime was more typically cross country.

“That time in Ghent was de Vlaeminck’s first. This happened – an outstanding road rider who had had recent success would be brought in by a promoter as a draw. It was good for the event. I did the same for Francesco Moser and Freddy Martens but it was very hard work for me – teaching them, coaching them through. I was the number one of the team so they arrived, learnt the track a little bit and then straight into the race.

“My best partner was Eddy. Of course, all partnerships start as commercial arrangements – the promoter puts the teams together, to get the best balance for the competition on the track. I raced with a lot of good racers, the best.”

“Were there any you didn’t get on with?”

An amused, slight raising of the eyebrows, the businessman who has no problem with telling an employee that he isn’t up to the job. “There was one. He was no good… I didn’t race with him again. But Eddy and I complemented each other. I was the speed, he was the strength and we were friends. That was very important. And he was always very motivated for the win. Every time. As was I.”

Two insights, there. Motivation – weirdly, not always a given with a professional rider – and the combination of the fast man whose job is to take the sprint laps and the strong man who can chase for lap advantage. This is the essence of the successful Six partnership.

When I ask Sercu about the friendship with Merckx, knowing that their intense rivalry on the road might have eclipsed their relationship off it, he says there was never any problem. But he makes a clear distinction between sporting ambition and mutual respect and affection.

Merkcx himself has said that you cannot like an adversary and although the two countrymen rode together with Solo-Superia for a year and then Faema for two years – when Sercu was still focusing more firmly on track racing – they became opponents when in 1970 Sercu joined a rival Italian team, Dreher, intending to step up his efforts on the road.

The move was something he later rued, if mildly. He is sure that he would have won more races had he stayed with Merckx and Merckx himself certainly resented the loss of such a good companion and exceptional sprinter – he was disappointed and showed it.

The 1970 Tour of Sardinia was Sercu’s first stage race win as a professional. Early on, Merckx punctured and missed a decisive break. Sercu took over as race leader. There were a lot of hills in the final stages. Sercu dreaded them but thought that his friend would – ought to – give him his head. They even discussed this one evening but Merckx’s attitude was rigid – he was there to win, Sercu was in a rival team, end of story.

Over the next few stages, The Cannibal attacked incessantly, Sercu hanging onto his wheel with bloody-minded tenacity. As Patrick puts it, he died a thousand deaths but kept the lead. (Merckx later won the race three times.)

That same year, Sercu was in the front group in the Ghent-Wevelgem with Merckx and two others. A sprint finish was his for the taking but Merckx never gave races away, except to faithful team men. He won and Sercu was, maybe, denied victory in a prestigious classic in his own backyard. One may imagine the satisfaction with which he trounced Merckx at the European track omnium shortly afterwards.

They rode together again with Fiat in 1977 and it was Sercu’s most prolific season. Quod erat demonstrandum?

His admiration for his lifelong friend is profound. On our first encounter, he told me how the day before the 1973 Liège-Bastogne-Liège, Flanders blasted by snow and rain, he was asked to ride by Brooklyn because de Vlaeminck was sick. His father drove him to the race start the next day in filthy weather and, through the windscreen, they saw a blurred shape on a bike riding along in the slush and wind… Merckx, on the way from his home in Brussels to the race.

“The thing about Eddy is that he was vaccinated with a spoke.”

Merckx won by five minutes that day.

The duo’s first win at the Ghent Six came out of the innocence of two young racers whose friendship was forged in an uncompromising dedication to the profession of cycle racing. As Sercu himself says of that bond, it’s not one that the professional hostility of being rivals in competition should be allowed to damage. They both rode to win, no matter where or against whom.

But what a profound effect it must have had on them, in their first season as pros, first time on the Ghent track in a Six, to ride their victory laps with the entire home crowd chanting their names.To be in the echo chamber of the Kuipke when a Belgian pair crosses the final line as winners and to be caught up in that fierce a volume of ecstatic rapture as the whole crowd lets rip is quite something. Partisan ain’t in it.

Patrick Sercu celebrates on the podium after his winning the Green jersey at the 1974 Tour de France

The photographer, stepping away from his tripod, lamp and reflector screen, interrupts briefly.

“Do you mind if I take pictures of your trophies?”

“Of course. But there are only a few cups here. The better things are in my study, through there.”

The phone rings. Sercu speaks for a few minutes in Flemish – business with the Ghent Six, for which he is race director. We resume.

Riders of his day rode through the winter because they needed to, whereas today’s riders are paid even for training and preparation. By contrast, as recently as the late ’80s, a pro contract covered no more than about half a year’s income. So, they raced as many as 150 days in the year. Television and the massive amounts paid by contemporary sponsors have changed everything.

Sercu explains the practicalities of his own career. As an amateur, he had ridden well on both track and road but it was not as easy to make money on the track, there were very few track teams and so his best option was to ride the full season of road races, stage and one day, and then the winter season of Sixes.

In 1969, the year he won his second professional world sprint title, he came 11th in Milan-San Remo, eighth in Paris-Roubaix, fifth in Ghent-Wevelgem, fourth in the Tour of Piedmont and then won six Sixes, five with his closest rival in Six-Day victories, Peter Post (rode 155, won 65). How on earth did he tolerate such a heavy mental and physical stress?

1974 Tour de France. Eddy Merckx, Raymond Poulidor and Patrick Sercu

He shrugs. “It’s how we were. Rik Van Steenbergen raced winter and summer…” The mention of the great Belgian fast man suggests an early inspiration. “You need good health, and the character – you need to like it.”

“And a tough mental attitude?”

“That, too. It’s head first then legs, remember. I never went one month without riding. I started with the big races in 1970, the Giro and some classics. I was older and a lot stronger so I could ride more.”

(According to Maurice Burton, who rode against him in the Sixes, Sercu used to weight his pedals with lead when training for the road after the track, to accommodate his legs to the slower cadences.)

The style of racing was different, too, more individual, less of a team affair. “In my time, I was a sprinter and all the others tried to eliminate the sprinters before they got to the finish.” Read that as the 1s seeking to burn off the fast men. The formidable Belgian teams which assured the victories of the two Maes brothers in the Tours of 1935 and ’36 were something of an oddity.

That kind of cohesion didn’t establish itself more widely, even in the Tour, until some while later. Sercu stresses the difference, especially amongst the riders who were used to the gloves-off scrap of the Belgian kermesses: the one day racing was more of a free for all. Only in the big stage races did teams begin to work more closely together, but they were encouraged to do that by the offer of a big pot of prize money.

Patrick Sercu stands on the podium after winning the sprint race at the 1967 World Track Cycling Championships.

“And what about the difference between the Sixes you rode and those of today?” I ask.

“They race far less, today. Now it’s more variation, more aerodynamic.”

His English is very good but, inevitably, peppered with odd locutions which need to be glossed. By aerodynamic, he means more closely programmed, streamlined, slick, scheduled and managed. The pattern of racing in Sercu’s day was fixed in the tradition of the Six, the reshaped race first developed in America, at Madison Square Garden.

Where modern riders race for as little as six hours in a day, Sercu et al were allotted as few as six hours for sleep. Add time out for massage and meals and they raced for some 16 hours a day.

The team that rode the greatest distance won the race as in the old days a rider had to be on track at any given moment – a particularly wearisome onus in the last hours before dawn, dutifully round a deserted stadium in a penumbral gloom, the main lights switched off, clocking up the laps, even slowly, at truce, all competition suspended.

Pictures show them, muffled up with scarf, gloves, extra top, woollen hat, leg warmers, one foot planted on the handlebars to steer, sometimes reading an early edition of the local paper, round and round at monotonous low tempo, just for form, eking out the demands of the contract.

The actual racing tended to finish at 2.30am but the promoter might keep the riders going if there was still a sizeable crowd bent on putting the beer away until around 4am when, in Zürich at least, the trams started up and the punters could go home for some shut eye, setting what the French call the ‘squirrels’ free from their treadmill at last.

I ask Sercu whether promoters ever offered bonuses to ginger up the racing. He is firm in his response: no. And what about alliances between teams? The same as on the road: now and again, to serve mutual interest, but when it came down to who took the win there was never a question of either selling or buying a race. When I ask whether money changed hands he gives me a look which registers that as a very silly question and says no.

There is something of the seigneur about Sercu, way beyond pride or hauteur. He needs no puff of attitude to exaggerate the distinction of his achievements. His manner is entirely charming and genial, his sense of his own worth understated and casual. And there was never any doubt of his standing, and status, round the tracks. He was known as The Phenomenon.

When the great Australian Six rider Danny Clark got his first contract – a last minute call, a rider had dropped out of the 1975 Frankfurt Six – he had to borrow bike and spare wheels. Sercu took one look at the wheels, told the new man they weren’t up to the job and loaned him a pair of his own.

When I mention Willy De Bosscher, ‘the clown’ (famous – infamous – for circus antics) he turns aside, expels a disdainful puff of air, a ‘get-outta-here’ gesture with his hand. Pah. All those antics on the track, the daft pranks, an offence to the true business of the Six…

“That’s not entertainment. If he was such a good entertainer, he should be at the Lido in Paris [the famous cabaret on the Champs Elysées]. No-one came for De Bosscher,” and he adds the telling proof: “He had no palmarès.”

Sercu still rides, but there’s a slight problem with the regularity of his heartbeat, so he never goes out more than once a week, depending on the weather.

“What kind of bike do you have?” Another silly question. He laughs. “A Merckx.”

We go into his study. A large picture of him on Ventoux – I recognise the scree of lauzes at once. “The first time I ever rode that mountain… and the last. Luckily it was early in the stage. Very, very hot.”

This was in 1974. He was riding for Brooklyn, the only Belgian in an all-Italian team with no real interest in the Tour. They entered as a favour to him. Sercu intended to ride for ten days or so but took the green jersey early on, didn’t want to give it up, and ultimately held it all the way to Paris. That was Merckx’s last victory in the Tour but his last participation wasn’t until 1977, with Sercu riding alongside him again – and taking three stages. Patrick retired in 1983 and rounded off 18 years as a pro with two Sixes: Rotterdam and Copenhagen.

“Would you like a drink?” he asks. “I don’t have any beer.”

We opt for water but then he says: “How about some champagne?”

And so we drink fizz, see through his fourth-floor window his old school, and, further across the roofscape of jostling houses – “I feel as if I am in Paris when I look out, you know” – the town football stadium and, hidden, the track where he began it all. Drinking champagne (Royer) with Mr Sercu… Santé.

This is an edited extract from Rouleur 28

Commenti

Posta un commento