Banned from the NCAA Tournament, Larry Brown and SMU Fight to Regain Their Pride

https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2616242-banned-from-the-ncaa-tournament-larry-brown-and-smu-fight-to-regain-their-pride

Bleacher report - FEBRUARY 15, 2016

DALLAS — Two days after their quest for an undefeated season ended with an 89-80 loss at Temple—dropping their record to 18-1—the SMU Mustangs erased any lingering bad vibes with a spirited, two-hour practice at Moody Coliseum.

The workout ended with a huddle near the baseline.

"We're back!" the players chanted as they broke the huddle. "We're back!"

Standing a few feet away, head coach Larry Brown could only smile and shake his head.

"Seriously," he said, "can you believe these kids? Their outlook, their attitudes? Unbelievable."

This wasn't the first time Brown had marveled at his team's resiliency.

He did it in March 2014, when the Mustangs reached the NIT title game after being inexplicably passed over for the NCAA tournament despite a 23-9 regular-season record and a third-place finish in the American Athletic Conference.

It happened again a year later, when Brown's players maintained their poise after a questionable goaltending call against SMU with 13 seconds remaining proved to be the difference in a 60-59 loss to UCLA—spoiling the program's first appearance in the Big Dance since 1993.

Nothing, though, was as painful as what occurred this past October, when Brown informed his team a few days before the official start of practice that the NCAA had imposed a one-year postseason ban on the Mustangs because of a single instance of academic fraud in Brown's program.

An investigation revealed that, in the summer of 2013, an administrative assistant completed an online course for incoming freshman Keith Frazier.

Brown was suspended for the first nine games of this season, a penalty that continues to irk him considering his claim that he knew nothing of the impropriety. Still, even more than the damage done to his own reputation, Brown remains livid that his players are being penalized for someone else's mistake.

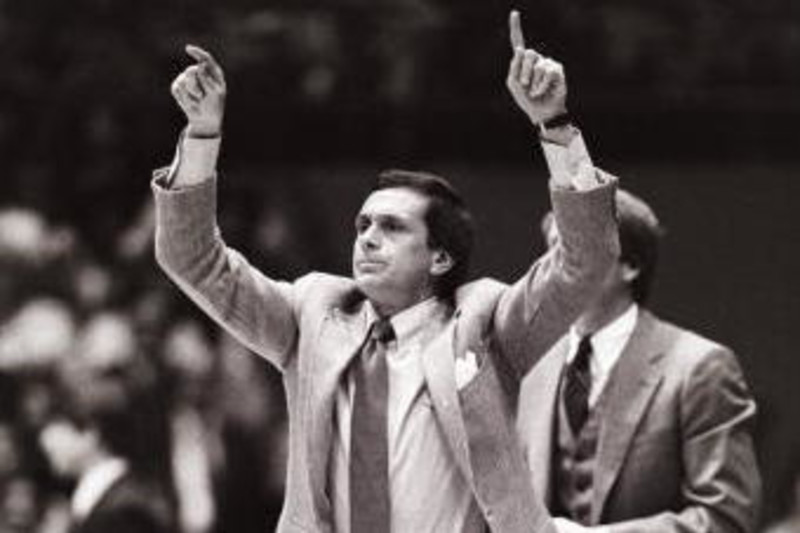

Tony Gutierrez/Associated Press

"I didn't get a good night's sleep for 16 months," said Brown, referring to the length of the investigation. "I knew something might happen, but when the verdict came down, I was 'There's no way they're serious. There's no way.'"

Brown paused.

"I'm a grown-up," he said. "I can deal with what happened to me. But what [the NCAA] did to those kids isn't fair. When I went in to tell my players, it was tough to even look at them."

Four months later, though, everyone's eyes are on the Mustangs.

And for all the right reasons.

Despite a roster that features just seven scholarship players, SMU will take a 21-3 record into Thursday's game against UConn. An 18-0 start catapulted the Mustangs to No. 8 in the Associated Press poll, their highest ranking since the 1984-85 season.

Sellout crowds have become a staple at Moody Coliseum as SMU attempts to win its second straight conference title. The Mustangs said they've been uplifted by the support and chuckle when people act surprised by the success of a team "that has nothing to play for."

"We've got a lot to play for," senior point guard Nic Moore said. "It's all about pride. When adversity hits, you just want to prove to the world how strong you are, that you're not going to let it bring you down."

Senior Nic Moore has helped spur the Mustangs to a 21-3 record this season

despite the fact that the team will not play in the NCAA Tournament.

Cooper Neill/Getty Images

Indeed, while some teams may have let it ruin their season, the NCAA's postseason ban didn't tear the Mustangs apart.

It united them.

To Moore, the morning of Sept. 30 remains a bit of a haze.

The senior remembers sitting next to his teammates as Brown, the head coach's assistants and school administrators entered the SMU locker room. He remembers athletic director Rick Hart informing the Mustangs of their postseason ban and then Brown saying something about making the most of the season.

Mostly, though, Moore remembers the ensuing silence.

"For a few minutes, no one said a word," Moore said. "It was kind of surreal. Everyone just dropped their heads and looked at the floor for a minute, and then we walked out and went our separate ways."

Assistant coach Tim Jankovich said the scene reminded him of a locker room after an NCAA tournament loss, when reality sets in that a season has come to its end.

"And ours hadn't even started," Jankovich said.

Still, heavy as the angst was in the locker room that day, the images etched in the brains of Brown and his assistants are the smiles the Mustangs had on their faces a few days later, when they showed up for their first official practice bouncing with energy as they prepared to move forward.

Keith Frazier quit the SMU team in January after an academic scandal

he was involved in saw the school get punished by the NCAA.

Ron Jenkins/Associated Press

"I thought, ‘Oh my God, we're going to have one of the worst, least-spirited practices ever,'" Jankovich said. "It was just the opposite. They were amazing. I was floored. If you'd have come to practice, you'd have had no idea what these guys had just been through.

"The [sanctions] irritated them so bad, it made them even more passionate."

Impressive as it was during preseason workouts, SMU took it to a new level the following month when they opened the 2015-16 campaign with 18 straight wins, a streak that included double-digit victories over Michigan and Stanford.

Making SMU's success even more noteworthy is that it has come without the services of several key players. Projected starter Semi Ojeleye, a highly regarded Duke transfer, elected to redshirt after the NCAA penalty was announced; and Ben Emelogu, a Virginia Tech transfer, was injured before the season and has yet to play.

Also missing is Frazier, the player at the center of the academic probe who quit the team in January after struggling with various issues off the court. Frazier was averaging 11.9 points.

"We tried to embrace him," Moore said. "We didn't hold anything against him. We've all made our mistakes in life. I put myself in his situation and said, 'What if it was me?' You can't really point your finger and blame him."

The most notable absence, though—at least early in the season—was on the sideline. As if being banned for the first nine games wasn't harsh enough, Brown wasn't even allowed to coach in practice.

For 34 days, the Hall of Famer (who won an NCAA title at Kansas and an NBA championship with Detroit) wasn't permitted to speak to his players or assistant coaches, whether it be in person or on the phone.

"One minute he was coaching the team the night before our first game, the next day he was gone for a month," said Jankovich, who served as interim coach in Brown's absence. "He had to completely vanish."

Brown, 75, said he considered using his free time to visit friends such as Bill Self at Kansas and John Calipari at Kentucky and sit in on their practices, but he feared he'd be a "nuisance." Instead, Brown remained in Dallas, spending time with his children and grandchildren and even sneaking in some golf when the weather was nice.

Brown was not permitted to speak to his players or assistant coaches

during his 33-day suspension from the program.

Tony Gutierrez/Associated Press

"People that know me assume I was going crazy," Brown said. "It was good to get away and catch my breath—but I was counting the days."

Some of Brown's most enjoyable moments, he said, came from watching the Mustangs' games on television. As pleased as he was with their play, Brown was even more encouraged by the positive comments commentators and analysts were making about his squad.

He felt the love in the community, too, whether it was from well-wishers at a high school game or the strangers sitting near him during his weekly coffee stops at Cafe de Brazil.

"People admire our kids for what they've been able to accomplish, fighting through so much adversity," Brown said. "It's not just about what's happened recently. It's about what happened the last two seasons. And it's about the perception of SMU, that people here don't care and will never support anybody.

"There are a bunch of people on this campus that want to prove people wrong."

Indeed, the support from SMU's fans has made Moody Coliseum one of the most daunting environments in college basketball. It certainly helped when Brown returned in Game 10, a 90-74 home win over Kent State on Dec. 22. The Mustangs' next eight victories included a two-point win over Cincinnati and a four-point triumph against Houston.

The team's three primary seniors—Moore, Jordan Tolbert and Markus Kennedy—average a combined 38 points and 17.2 rebounds.

"My mom always told me to prepare for the worst," Tolbert said. "If you prepare for the worst, you'll be ready for anything. What happened to us was bad, but [we] accepted it and moved on. Even if we don't have postseason to play for, it's still basketball. We still love the game. It's still fun."

At 18-0, now-16th-ranked SMU was the country's lone undefeated team when it lost a Jan. 24 road game to Temple, where fans stormed the court after the final horn. Brown actually took a bit of pleasure in the opposing team's celebration. Less than four years after taking over the long-struggling program, a win over the Mustangs was now considered a monumental feat.

Temple's jubilation at dealing SMU their first defeat this season struck

Brown as a sign of how much the Mustangs' level of respect has grown.

Matt Slocum/Associated Press

That it occurred during a season of such turmoil made it even more meaningful.

"I'm blown away being around them," Brown said. "They've brushed aside every obstacle that could've kept them from being resilient. I'm in awe of what they've done. They've moved on."

If only it was as easy for Brown to do the same.

Multiple times in the days after the NCAA penalties were announced, Brown received phone calls from his son, L.J., and his daughter, Madison—both of whom attend SMU—alerting him of newspaper and Internet articles that contained attacks on his character.

Words such as "cheater" and "liar" were staples in each opinion piece. All across the nation, folks were calling for Brown to be fired.

"They were, like, 'Dad, we know this isn't you. We know this isn't who you are,'" Brown said. "It's painful to know your kids are having to read that."

Brown paused.

"It hurt me to hear people say those things," Brown said. "It bothered me."

Almost five months later, it still does.

Brown has said repeatedly that he didn't know that his administrative assistant was taking the online course for Frazier, a claim the NCAA backed up in its report. Still, the NCAA maintains that head coaches—whether they're involved in a violation or not—are ultimately responsible for everything that goes on in their program.

"If that new rule wasn't in place, I wouldn't even be involved in this," Brown said.

Jon Duncan, the NCAA's vice president for enforcement, said the rule that holds coaches ultimately accountable isn't new at all, adding that it's been in place since 2005.

Jeffrey McWhorter/Associated Press

Duncan also said the guideline doesn't call for "strict liability" and that coaches have the opportunity to clear their name during the investigative process.

"We don't require them to be all-knowing or mini-investigators," said Duncan, who is not allowed to talk about SMU's case specifically. "The rule [requires] them to show that an atmosphere of compliance exists within their program, that they proactively communicate to their staff that being in compliance is paramount.

"And they need to show that they monitor their staff and, when red flags arrive, that they engage and ask questions and inform their compliance department of any issue."

Proving those efforts were made at a high degree, Duncan said, can result in the allegation against the head coach being revoked.

Another reason Brown was hit with a nine-game suspension was because the NCAA believed he provided misleading information during the investigative process, although the NCAA noted in its report that Brown corrected himself within minutes of making the false statement after speaking with his lawyer.

"I got blindsided with a question," Brown said. "I left the room for 60 seconds and came back in and gave them the right answer.

"For the NCAA to say I lied...they know that's not true. If you lie you get fired. It's unethical conduct. They know if I had committed unethical conduct, I wouldn't still have my job. I left the room and came back 60 seconds later to correct myself, and they even said, 'That's not a lie.' The [NCAA] lady told me, 'I admire the fact that you would do that. Other people wouldn't have done that.' Yet then they turned around and said I lied and penalized me for it."

One person who has come to Brown's defense is ESPN's Jay Bilas, who has a law degree and has long been regarded as one of the most influential voices in college sports.

"The NCAA doesn't allow for human behavior," Bilas said. "No one is saying that not being completely forthcoming isn't the right thing. But when someone is navigating a very difficult process, one that could be scary and confusing and has a lot of different interests at stake, it's easy to see how that could happen.

A year after leading Kansas to the NCAA title, Larry Brown saw Kansas banned from the

NCAAs because of a plane ticket he had helped a player purchase a few years earlier.

Richard Sheinwald/Associated Press

"For Larry Brown to make an error in judgment about how he responded, and then to fix it right there on the spot, and to still have that held against him? That doesn't send a very positive message from the NCAA."

Even more disturbing to Brown, however, is the insinuation that he's a habitual cheater.

While it's true all three of his college coaching stints (UCLA, Kansas and SMU) have been marred by probation, Brown said it's inaccurate and unfair to label him as a rule-breaker who has no regard for NCAA policies.

"I heard guys like [Dick] Vitale say things," Brown said. "And then I read stories from reporters who are too lazy to go back and research what happened at Kansas and UCLA. None of these people make any calls. They don't call me. They don't call my former athletic directors. They just write whatever gets [attention]."

In 1989, Kansas was banned from the NCAA tournament—marking the first time ever a school was unable to defend its national title—after Brown was found to have given $364 to recruit Vincent Askew three years earlier. The money was for a round-trip plane ticket for Askew to visit his ill grandmother, who ended up passing away.

In most scenarios, the violation wouldn't have been serious enough to warrant probation, but the Kansas football program had been placed on probation in 1983, and the school had been informed that a second violation, in any sport, would result in stiff penalties.

Nearly one decade earlier, the NCAA forced Brown's UCLA squad to vacate a 1980 Final Four appearance when two players were deemed ineligible, but Brown said that penalty stemmed from issues that existed well before he was hired.

"There were 90 violations at UCLA before I even got there," Brown said. "I was told to come in and clean [stuff] up. But no one wants to write that. It sounds better to say, 'He got three schools on probation.'"

Brown says that the violations for which UCLA was penalized after

he took over the program predated his arrival at the school.

George Gojkovich/Getty Images

Brown, who left UCLA for the New Jersey Nets after the 1980-81 season, said the Bruins tried to re-hire him years later. He also said schools such as Stanford, Colorado and others offered him their head coaching positions after a thorough vetting.

"Why would those schools try to hire me if what I did was so wrong?" Brown said. "You don't think a private school like SMU vetted me? Why would they hire me if they thought I was like that? And why wouldn't they have fired me if they thought I was guilty of any wrongdoing in this situation?"

Bilas said he understands Brown's frustrations about the light in which he's been cast.

"People are so cavalier when they try to link things that aren't linked," Bilas said. "That is to say, 'Well, he got UCLA on probation, and he got Kansas on probation, and now this.'

"That's such a facile and weak and lazy interpretation of things. UCLA was about [notorious booster] Sam Gilbert, and the truth is, that was not Larry Brown. That was an institutional thing that had been going on for years. He was just left holding the bag at the end.

"Then the issue at Kansas…the probation came because football had just been hit. If it would've just been basketball, probation would not have occurred.

"To say that he's a third-time offender and major, habitual cheater is unfair."

Michael Littwin worked for the Los Angeles Times during Brown’s tenure at UCLA and, along with colleague Alan Greenberg, broke the story about the violations involving Gilbert and UCLA players that had been occurring for years.

Littwin said the Times never uncovered any wrongdoing by Brown.

"Whatever happened during Larry's tenure at UCLA was all a dying remnant of the Sam Gilbert scandal, one that Larry didn’t know how to handle, one that went back to the days of John Wooden," Littwin said.

"When Larry left UCLA, no one accused him of being a cheater. No one pegged that on him. He wasn't considered damaged goods."

In an article published April 3, 1989, longtime Sports Illustrated writer Alexander Wolff confirmed Littwin's report that Brown was shocked by the ties that Gilbert had formed with UCLA players and that the two had an adversarial relationship.

Though he has presided over three programs that have felt the wrath of the NCAA enforcement arm, Brown asks, "Why wouldn't [SMU] have fired me if they thought I was guilty of any wrongdoing?"

Lance King/Getty Images

Wolff wrote: "After becoming the UCLA coach in the late '70s, Larry Brown, who resented Gilbert's sway with his players, tried to run him off. Gilbert responded by threatening not only to cut off Brown's testicles but also to do it 'without him even knowing it.'"

More than three decades later, Brown admits there are things he could’ve done differently.

At SMU, he said his one regret is that, upon learning of the academic impropriety in his program, he waited a month to tell Hart, his athletic director. Brown said the NCAA had already begun its investigation when he heard the news and that he assumed it would get discovered.

"Hindsight is 20-20," he said. "I probably should've told [Hart]. But it wouldn't have changed what happened."

Even before the violation at SMU, Brown said the school had taken multiple steps to ensure the basketball program followed NCAA rules. He said Kyle Conder, the school's senior associate athletics director for compliance, has an office in SMU's basketball headquarters and meets with Brown every day, even keeping a journal of every conversation. Conder also accompanies the Mustangs on all road trips, Brown said, and meets with every recruit.

Also on the staff is Jankovich, who has been either a head coach or an assistant at 13 different schools.

"Tim testified to the NCAA that he's never been in a program that makes more of an effort to abide by the rules as we do," Brown said. "Yet they said we didn't have an atmosphere of compliance. That's a big bunch of crap. They never asked our compliance guy anything.

"Look, I realize a mistake was made, a mistake we knew nothing about. If I have to take the blame for that because I'm the head coach, so be it. But the penalty doesn't fit the crime. Another school had kids getting money for years, kids playing when they were ineligible, kids failing drug tests for years...it was a litany of things. They got the exact same penalty as us. Read what we did and read what they did and tell me if you think we were treated fairly."

Although Brown didn't name the school, he was likely referring to Syracuse, which enforced a self-imposed postseason ban last year.

Duncan pointed out the NCAA Committee on Infractions—and not the NCAA Enforcement staff—determines the severity of the penalties following the enforcement's staff’s investigation and the subsequent hearing that ensues.

"We don't celebrate penalties," Duncan said. "We don't do high-fives and cartwheels when penalties are imposed. Those are heavy days for us. We don't take any pleasure in that. But we have an obligation. We're not trying to punch [violators] in the nose; we're trying to protect those playing by the rules."

Frustrated as he is that his reputation has been muddied, Brown continues to surge forward. He said the people closest to him "know who I am. They know what I'm about. In the end, that's all that really matters."

Plus, Brown is excited about his team—or rather, his program.

As good as the Mustangs are this year, there may be even better days ahead. SMU will lose seniors Tolbert, Moore and Kennedy. But Ojeleye and Emelogu will join a 2016-17 cast of returnees that includes second-leading scorer (12.1 points per game) and rebounder (7.1 rpg) Ben Moore along with promising freshman Shake Milton (10.9 ppg).

Standout guard Sterling Brown (9.6 ppg) will also be back, and SMU could add as many as six recruits.

The positive outlook is one of the main reasons Brown scoffs at rumors that he might retire, that the frustrations over the NCAA penalties might drive him away from the college game for good.

"I always thought we could be a Top 20 program annually," Brown said. "Now we're there—so why the hell would I leave now? We're ready to take off.

"Not that we haven't already."

Jason King covers college sports for Bleacher Report.

You can follow him on Twitter @JasonKingBR.

Commenti

Posta un commento