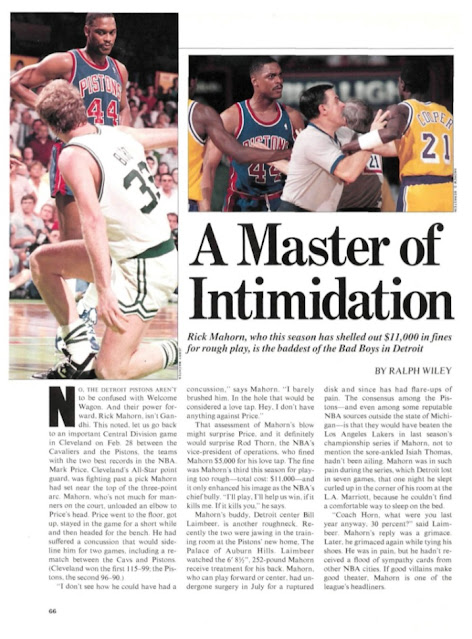

A MASTER OF INTIMIDATION

by RALPH WILEY

Sports Illustrated - April 10, 1989

No, the Detroit Pistons aren't to be confused with Welcome Wagon. And their power forward, Rick Mahorn, isn't Gandhi. This noted, let us go back to an important Central Division game in Cleveland on Feb. 28 between the Cavaliers and the Pistons, the teams with the two best records in the NBA. Mark Price, Cleveland's All-Star point guard, was fighting past a pick Mahorn had set near the top of the three-point arc. Mahorn, who's not much for manners on the court, unloaded an elbow to Price's head. Price went to the floor, got up, stayed in the game for a short while and then headed for the bench. He had suffered a concussion that would sideline him for two games, including a rematch between the Cavs and Pistons. (Cleveland won the first 115-99; the Pistons, the second 96-90.)

"I don't see how he could have had a concussion," says Mahorn. "I barely brushed him. In the hole that would be considered a love tap. Hey, I don't have anything against Price."

That assessment of Mahorn's blow might surprise Price, and it definitely would surprise Rod Thorn, the NBA's vice-president of operations, who fined Mahorn $5,000 for his love tap. The fine was Mahorn's third this season for playing too rough—total cost: $11,000—and it only enhanced his image as the NBA's chief bully. "I'll play, I'll help us win, if it kills me. If it kills you," he says.

Mahorn's buddy, Detroit center Bill Laimbeer, is another roughneck. Recently the two were jawing in the training room at the Pistons' new home. The Palace of Auburn Hills. Laimbeer watched the 6'8½", 252-pound Mahorn receive treatment for his back. Mahorn, who can play forward or center, had undergone surgery in July for a ruptured disk and since has had flare-ups of pain. The consensus among the Pistons—and even among some reputable NBA sources outside the state of Michigan—is that they would have beaten the Los Angeles Lakers in last season's championship series if Mahorn, not to mention the sore-ankled Isiah Thomas, hadn't been ailing. Mahorn was in such pain during the series, which Detroit lost in seven games, that one night he slept curled up in the corner of his room at the L.A. Marriott, because he couldn't find a comfortable way to sleep on the bed.

"Coach Horn, what were you last year anyway, 30 percent?" said Laimbeer. Mahorn's reply was a grimace. Later, he grimaced again while tying his shoes. He was in pain, but he hadn't received a flood of sympathy cards from other NBA cities. If good villains make good theater, Mahorn is one of the league's headliners.

The 30-year-old Mahorn has had run-ins, scowl-offs and dustups with the best of them, including Akeem Olajuwon of the Houston Rockets, Larry Nance of the Cavaliers, five Chicago Bulls and their coach, Doug Collins, all at once, and even (gasp!) Michael Jordan and Larry Bird. Who can forget the Mahorn hip that sent Bird sliding across the Silverdome floor in 1987? Certainly nobody who follows pro basketball. "Rick's thing is intimidation," says Steve Jones, who broadcasts NBA games for TBS. "The kind that wears on you. He wants you so agitated you forget the game."

New York Knick center Patrick Ewing, who played pickup games against Mahorn when Ewing was at Georgetown and now has to face him as a pro, says, "He's a great defender. He knows all the tricks. He can push you out, then pull the chair and make you fall flat on your butt. Until this day, when I play Rick Mahorn, I know it's going to be a war."

"My reputation is unfounded," says Mahorn. "I can play. I wouldn't have been in this league for nine years if I couldn't play. Thug this, enforcer that. I take 48 minutes very seriously, that's all. When you consider who I have to guard...."

Mahorn takes the opposition's low-post scorer. "That means Ewing, Kevin McHale, Charles Barkley, Moses Malone and Mailman Malone—every night," says Mahorn. "You know anybody who wants that?"

"Rick brings a maturity, unselfishness and a glue to our club," says Detroit coach Chuck Daly. "We need that defensive rebounding, and we really need that low-post D."

Indeed, from Jan. 27—when Mahorn returned to the Pistons' lineup after having missed 10 games because of a recurrence of back pain—through last weekend, the Pistons went 27-5 and overtook the Cavaliers for the best record (53-17) in the league. "We have our game," says Laimbeer, who has been fined $6,000 for rough stuff this season. "We cut a place in this league."

They certainly do, which is why Laimbeer and Mahorn have such deserved reputations and why the Pistons are known as the Bad Boys around the NBA. "Rick protects me," says Laimbeer. "There are a lot of guys in the league who might want to fight me, but they hesitate when they see Rick there."

While the 6'11" Laimbeer is grateful for Mahorn's protection on the floor, he thinks Mahorn's notoriety is unwarranted. In fact, Laimbeer will tell you that Mahorn is just a big teddy bear away from the court. "Rick is one of the warmest people," says Laimbeer. "There's nothing he wouldn't do for a friend or a person in need."

Mahorn is from Hartford, Conn., where he and his older brother, Owen Jr., and his sisters, Audrey and Pam, grew up in an apartment with their mother, Alice. One day, when Rick was eight months old, his father, Owen, who was a dock manager at a local milk plant, walked out. "He was always well liked," says Alice. "He had other things on his mind. Responsibility wasn't one."

When Alice went off to do what she called "day's work" in the finer houses of Hartford, she would admonish Owen Jr., who is five years older than Rick, to be his brother's keeper. Owen was an athletic kid, but Rick was fat and weak as a youngster. "As soon as she got out of the house, he'd beat me up," says Rick. "But when I couldn't take care of myself, when the boys would say, 'What are you doing here, fat boy?' my brother took care of me. I can beat him up,' he'd tell them, 'but you will leave him alone.' "

Owen later played basketball at Fairfield University, while Rick grew from 6'1" to 6'7" during his 16th summer. He became a tight end and defensive end at Weaver High but didn't start for the basketball team until his senior year. He could take care of himself by then. Although he received far more scholarship offers for football than for basketball, he decided to play basketball.

"It was my second year in college before I finally beat Owen in one-on-one," says Mahorn. "That was the sweetest feeling in the world. Now I'm living Owen's dream. He doesn't know he could never be as proud of me as I am of him."

"Ask Horn about being institutionalized," says Laimbeer with a laugh. Mahorn grimaces at Laimbeer. "I'll get old Lame Butt for that one later," says Mahorn. Laimbeer has the role of the weak little brother now. Mahorn can beat him up, but he won't let anyone else do it. As for being institutionalized, Mahorn went to college at Hampton Institute. By the time he graduated, with a degree in business administration, he had become the most successful basketball player in the history of the school.

The Washington Bullets picked Mahorn, the first player from Hampton ever drafted by the NBA, in the second round of the 1980 draft. A year later the Bullets signed 6'11", 275-pound Jeff Ruland, who had been playing in Spain, and for four seasons he and Mahorn formed an intimidating inside tandem, one that Boston Celtics announcer Johnny Most dubbed McFilthy [Ruland] and McNasty [Mahorn].

"If anybody is my beef brother, bruise brother, whatever, it's Ruland," says Mahorn. "We had the same kind of dog—black Dobermans. Our kids were the same age. His license plate was GTM 677. And by coincidence, mine was GTM 877. We were the same kind."

And they played the same kind of game. While Owen Jr. had to protect Rick and while Horn has to look after Laimbeer, Mahorn and Ruland were equals. "Rick and I talk all the time," says Ruland, who is now retired.

In June 1985, Washington traded Mahorn and the rights to center-forward Mike Gibson to Detroit for forward Dan Roundfield. "I was shocked," says Mahorn. "I learned the game from Wes Unseld, alongside Jeff Ruland. I felt at home in Washington."

Says Unseld, who now coaches the Bullets, "I was shocked, too, but it happens. He had endeared himself to me. Ninety-nine percent of the guys don't want the job Rick has. A lot of people have problems with the way he plays. I have no problem with it. If you come in there weak. Rick will make you pay."

Mahorn lives in a spacious, nicely decorated apartment in the Riverfront development in downtown Detroit. The rest of the Pistons live near The Palace, a good 25 miles north of Mahorn's digs. During the off-season, he sometimes stays at his mother's place in Hartford. "Rick came by one day and said, 'Mommy, I want you to see this house,' " says Alice. "I thought we were looking for him." Mahorn bought Alice that house—all 22 rooms of it.

Only two pictures are on display in Mahorn's apartment. One is of his mother. The other is of his six-year-old daughter, Moyah, who often spends time with her father. (Mahorn is estranged from Moyah's mother.) "Not enough, though, never enough," says Mahorn of his desire to see his child. "She's my heart, my light, my life." So yes, when Mahorn isn't getting fined for passing out love taps, he really is just a big old teddy bear. He recently befriended a young unwed mother and bought her baby a few outfits of clothing merely because Leon (The Barber) Bradley, the Pistons' self-designated No. 1 fan, had asked him for help. Mahorn also donates time to the South Arsenal Neighborhood Development programs for kids in Hartford, and with respect and affection, he sends Alice a Father's Day card every year.

"At one time the things said about my son bothered me," she says. "Not anymore. If anyone takes the time to know Ricky, they'll see what kind of man he is. Ricky has a job to do." She pauses and continues, "He has his day's work."

Mahorn's day's work is twofold. He gives the Pistons a chance to win a championship, and he gives the crowd someone to boo. After all, he is a good villain.

Commenti

Posta un commento