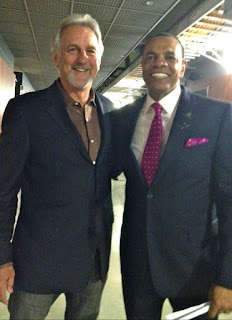

Two basketball lifers and their friendship: The Hollins and Westphal story

http://nypost.com/2014/10/04/from-phoenix-in-the-70s-to-brooklyn-now-the-hollins-and-westphal-story/

By Tim Bontemps

By Tim Bontemps

October 4, 2014 | 12:11am

To know the relationship between Lionel Hollins and Paul Westphal you have to go back to the late 1970s, when Westphal was an All-Star shooting guard and go-to scoring option for the Suns, and Hollins was the defensive stopper for the Trail Blazers tasked with slowing him down whenever the two teams faced one another.

“I held him and grabbed him and beat him up,” Hollins, now the head coach of the Nets, said of Westphal, his assistant coach, with a smile after a practice earlier this week. “He was a great scorer, had great footwork and made scoring look easy, but I had a lot of athleticism and competitiveness and toughness, and so I battled from that perspective.”

Westphal was equally complimentary of Hollins.

“He was such a great competitor,” Westphal said. “He liked taking on the challenge of playing defense, and he liked to get under your skin, but he didn’t do it in a way that was disrespectful to the game or the opponent.

To know the relationship between Lionel Hollins and Paul Westphal you have to go back to the late 1970s, when Westphal was an All-Star shooting guard and go-to scoring option for the Suns, and Hollins was the defensive stopper for the Trail Blazers tasked with slowing him down whenever the two teams faced one another.

“I held him and grabbed him and beat him up,” Hollins, now the head coach of the Nets, said of Westphal, his assistant coach, with a smile after a practice earlier this week. “He was a great scorer, had great footwork and made scoring look easy, but I had a lot of athleticism and competitiveness and toughness, and so I battled from that perspective.”

Westphal was equally complimentary of Hollins.

“He was such a great competitor,” Westphal said. “He liked taking on the challenge of playing defense, and he liked to get under your skin, but he didn’t do it in a way that was disrespectful to the game or the opponent.

“He would just fight you for every inch. There was a lot of respect involved.”

That yin and yang, those two different approaches to the game at which they both excelled helped forge a friendship between them that began during an offseason exhibition tour of Europe when both were still playing, and has lasted nearly 40 years.

When Hollins was putting together his coaching staff this summer, he knew he wanted to bring aboard Westphal, with whom he had worked under Cotton Fitzsimmons in Phoenix 25 years earlier, and for whom he worked as an assistant when Westphal was elevated to replace Fitzsimmons a few years later.

“I wouldn’t have [been an assistant] in any situation,” Westphal said of taking the Nets job. “I wasn’t desperate to go find a situation, but I definitely wouldn’t have said no to Lionel.

“I love the game, and I love being part of it. This is a perfect spot for me, and a perfect time.”

The reunion of Hollins and Westphal in Brooklyn is a continuation of their highly successful run in Phoenix, which began when Fitzsimmons brought on Westphal — who had just won an NAIA title at nearby Grand Canyon College — as an assistant. He then brought on Hollins — who had been volunteering at Arizona State (where he had starred in college) while finishing his degree — as his other assistant at Westphal’s recommendation.

“It was his character,” Westphal said in explaining why he had recommended Hollins. “I knew who he was as a man, and I knew the respect he had for the game.

“It was an easy call. He was ready, and we were lucky to get him.”

Westphal had a long relationship with the Suns organization from his playing days, and Hollins had been going to Fitzsimmons’ offseason camps in the head coach’s hometown of Hannibal, Mo., so both were comfortable with their boss and comfortable with each other. They formed a strong partnership that mirrored their playing days — Westphal focusing on offense, and Hollins on defense.

“Well, we felt that each, in their own right, brought certain traits and characteristics to the table,” said Jerry Colangelo, a longtime Suns executive who became the team’s owner in 1987. “Like putting together any staff, you don’t want to have redundancy, and certainly I think they each represented a little bit different a twist to their abilities.”

The Suns immediately became a contender under Fitzsimmons, winning at least 53 games in each of his four years in charge — advancing to the Western Conference Finals his first two years — with Westphal and Hollins on the bench.

With both men only a few years removed from their NBA careers, they spent plenty of time playing 1-on-1 after practice in an attempt to keep their competitive juices flowing — though, at times, those juices flowed a little too freely.

“We had many harsh battles when we were assistant coaches,” Hollins said. “We would beat each other up and almost come to blows. … We almost got to a point where we didn’t speak to each other.”

It was at that juncture, both men said, their wives got involved.

“Our wives had to stop us from playing [against each other],” Westphal said with a laugh. “We would be so mad at each other, and we would come home saying, ‘Oh, he was fouling me,’ or ‘Oh, he was flopping.’ ”

So instead of playing 1-on-1, they started playing 2-on-2 and 3-on-3 with the Suns’ young players, bringing the same competitive fire they had in their 1-on-1 games to those matchups. They weren’t beating on each other anymore (they always played on the same team), but they had no issues with beating up on the inexperienced Suns.

“The problem was, they were the best two players on the floor,” Steve Kerr, a rookie with the Suns in the 1988-89 season and now coach of the Warriors, said with a laugh Friday afternoon. “They were great. They were very encouraging.

“They helped me kind of lay the foundation for my own career and taught me about the league … along with kicking my ass everyday afterwards in 3-on-3.”

They also were instrumental in the development of swingman Dan Majerle, who was drafted in the first round in 1988 by the Suns. After spending his collegiate career at Central Michigan as a post player, Majerle transitioned into being an offensive threat and a defensive stopper on the perimeter, and credited both Westphal and Hollins for helping him make that transition.

“To have both of those guys be experienced, veteran NBA players now coaching me as a young player coming into the league, and helping me understand the league, was a perfect situation for a guy like myself,” Majerle said.

Once Fitzsimmons stepped down as head coach after the 1991-92 season and Westphal was elevated to the top job, little changed between the two men, who still saw it as a partnership in which either was comfortable saying anything to the other.

“Seamless,” Westphal said of the transition. “Our strengths and weaknesses compliment each other, and yet we still saw the vision of the game, and what it should be, the same.”

“It never changed,” Hollins said of their relationship after Westphal’s promotion. “We were good friends. … Like now, he gives me advice and tells me stuff and makes suggestions, the same way we did when he was head coach.

“Now I’m the one who makes the final decision, versus him making the final decision … but the way we interact is the same.”

Their run in Phoenix ended after a trip to the NBA Finals in 1993 — when the Suns lost in six games to Michael Jordan’s Bulls — and back-to-back losses in the Western Conference semifinals to the eventual champion Rockets in 1994 and ’95. The two went their separate ways in the coaching world, with Westphal serving head-coaching stints with the Sonics and Kings on either side of a five-year run in the college ranks at Pepperdine, and Hollins having multiple stints with the Grizzlies, including his successful run from 2009 through the end of the 2013 season.

While both were out of the league last season, they met up in Nashville and Hollins asked his old friend if, under the right circumstances, he would consider being an assistant coach at some point in the future.

“It was just a question I was asking,” Hollins said. “But he said, ‘No, if it’s the right opportunity, I’d do it.’”

When Jason Kidd’s stunning departure from Brooklyn in early July led to the Nets hiring Hollins as their new head coach, bringing in Westphal to be part of his staff was an easy call.

“It’s great to be back with him,” Hollins said. “I think he’s one of the most creative people offensively that’s coached in this league, and I’m happy he’s willing to come in and be my assistant after I was his assistant.”

And for Westphal, after spending the previous year and a half out of the league, getting a chance to not only return to the NBA, but also to do so working for an old friend was simply too good to pass up.

“It’s poetic justice in a lot of ways,” he said. “It just feels right.

“I’ve always helped him right up at the top of guys that I’ve respected in the league, and we had years of playing against each other and working with each other and against each other, too.

“To be co-assistants and then he was my assistant, and to now be his assistant … it just seems so perfect.”

That yin and yang, those two different approaches to the game at which they both excelled helped forge a friendship between them that began during an offseason exhibition tour of Europe when both were still playing, and has lasted nearly 40 years.

When Hollins was putting together his coaching staff this summer, he knew he wanted to bring aboard Westphal, with whom he had worked under Cotton Fitzsimmons in Phoenix 25 years earlier, and for whom he worked as an assistant when Westphal was elevated to replace Fitzsimmons a few years later.

“I wouldn’t have [been an assistant] in any situation,” Westphal said of taking the Nets job. “I wasn’t desperate to go find a situation, but I definitely wouldn’t have said no to Lionel.

“I love the game, and I love being part of it. This is a perfect spot for me, and a perfect time.”

The reunion of Hollins and Westphal in Brooklyn is a continuation of their highly successful run in Phoenix, which began when Fitzsimmons brought on Westphal — who had just won an NAIA title at nearby Grand Canyon College — as an assistant. He then brought on Hollins — who had been volunteering at Arizona State (where he had starred in college) while finishing his degree — as his other assistant at Westphal’s recommendation.

“It was his character,” Westphal said in explaining why he had recommended Hollins. “I knew who he was as a man, and I knew the respect he had for the game.

“It was an easy call. He was ready, and we were lucky to get him.”

Westphal had a long relationship with the Suns organization from his playing days, and Hollins had been going to Fitzsimmons’ offseason camps in the head coach’s hometown of Hannibal, Mo., so both were comfortable with their boss and comfortable with each other. They formed a strong partnership that mirrored their playing days — Westphal focusing on offense, and Hollins on defense.

“Well, we felt that each, in their own right, brought certain traits and characteristics to the table,” said Jerry Colangelo, a longtime Suns executive who became the team’s owner in 1987. “Like putting together any staff, you don’t want to have redundancy, and certainly I think they each represented a little bit different a twist to their abilities.”

The Suns immediately became a contender under Fitzsimmons, winning at least 53 games in each of his four years in charge — advancing to the Western Conference Finals his first two years — with Westphal and Hollins on the bench.

With both men only a few years removed from their NBA careers, they spent plenty of time playing 1-on-1 after practice in an attempt to keep their competitive juices flowing — though, at times, those juices flowed a little too freely.

“We had many harsh battles when we were assistant coaches,” Hollins said. “We would beat each other up and almost come to blows. … We almost got to a point where we didn’t speak to each other.”

It was at that juncture, both men said, their wives got involved.

“Our wives had to stop us from playing [against each other],” Westphal said with a laugh. “We would be so mad at each other, and we would come home saying, ‘Oh, he was fouling me,’ or ‘Oh, he was flopping.’ ”

So instead of playing 1-on-1, they started playing 2-on-2 and 3-on-3 with the Suns’ young players, bringing the same competitive fire they had in their 1-on-1 games to those matchups. They weren’t beating on each other anymore (they always played on the same team), but they had no issues with beating up on the inexperienced Suns.

“The problem was, they were the best two players on the floor,” Steve Kerr, a rookie with the Suns in the 1988-89 season and now coach of the Warriors, said with a laugh Friday afternoon. “They were great. They were very encouraging.

“They helped me kind of lay the foundation for my own career and taught me about the league … along with kicking my ass everyday afterwards in 3-on-3.”

They also were instrumental in the development of swingman Dan Majerle, who was drafted in the first round in 1988 by the Suns. After spending his collegiate career at Central Michigan as a post player, Majerle transitioned into being an offensive threat and a defensive stopper on the perimeter, and credited both Westphal and Hollins for helping him make that transition.

“To have both of those guys be experienced, veteran NBA players now coaching me as a young player coming into the league, and helping me understand the league, was a perfect situation for a guy like myself,” Majerle said.

Once Fitzsimmons stepped down as head coach after the 1991-92 season and Westphal was elevated to the top job, little changed between the two men, who still saw it as a partnership in which either was comfortable saying anything to the other.

“Seamless,” Westphal said of the transition. “Our strengths and weaknesses compliment each other, and yet we still saw the vision of the game, and what it should be, the same.”

“It never changed,” Hollins said of their relationship after Westphal’s promotion. “We were good friends. … Like now, he gives me advice and tells me stuff and makes suggestions, the same way we did when he was head coach.

“Now I’m the one who makes the final decision, versus him making the final decision … but the way we interact is the same.”

Their run in Phoenix ended after a trip to the NBA Finals in 1993 — when the Suns lost in six games to Michael Jordan’s Bulls — and back-to-back losses in the Western Conference semifinals to the eventual champion Rockets in 1994 and ’95. The two went their separate ways in the coaching world, with Westphal serving head-coaching stints with the Sonics and Kings on either side of a five-year run in the college ranks at Pepperdine, and Hollins having multiple stints with the Grizzlies, including his successful run from 2009 through the end of the 2013 season.

While both were out of the league last season, they met up in Nashville and Hollins asked his old friend if, under the right circumstances, he would consider being an assistant coach at some point in the future.

“It was just a question I was asking,” Hollins said. “But he said, ‘No, if it’s the right opportunity, I’d do it.’”

When Jason Kidd’s stunning departure from Brooklyn in early July led to the Nets hiring Hollins as their new head coach, bringing in Westphal to be part of his staff was an easy call.

“It’s great to be back with him,” Hollins said. “I think he’s one of the most creative people offensively that’s coached in this league, and I’m happy he’s willing to come in and be my assistant after I was his assistant.”

And for Westphal, after spending the previous year and a half out of the league, getting a chance to not only return to the NBA, but also to do so working for an old friend was simply too good to pass up.

“It’s poetic justice in a lot of ways,” he said. “It just feels right.

“I’ve always helped him right up at the top of guys that I’ve respected in the league, and we had years of playing against each other and working with each other and against each other, too.

“To be co-assistants and then he was my assistant, and to now be his assistant … it just seems so perfect.”

Commenti

Posta un commento