The Graham Jones Story

by Duncan Hamman (Abbotsford Park RC)

bikedunc@btinternet.com

THE BEGINNING

It began one winter's evening in 1972 when a 15 year old boy visited the clubroom of the Abbotsford Park Road Club, a Manchester cycling club, which was situated in Hart Road, Fallowfield. The other members present made the boy welcome, a membership form was produced and the boy quickly became the club's newest member. His name was Graham Jones and, like most 15-year-old cyclists, he had dreams of, one day,riding in the greatest cycle race in the world - The Tour de France. Unlike most dreams, however, this one would come true and Graham would ride in this great race no fewer than five times.

JUNIOR YEARS

At school Graham was sports mad. He played most sports and was good at all of them. He repesented Manchester at both football and basketball and was lined up for a test with Manchester United. Had he not been bitten by the cycling bug he could have ended up playing for the 'Reds'. The Jones family lived in Fallowfield and Graham’s older brother would take him to the old cycling stadium to see the racing. He remembers when he was ten years old all the spectators standing for a minutes silence when Tom Simpson lost his life in the Tour de France in 1967. Little did he realise then that later in his life he would follow in Tom's footsteps and ride for the Peugeot Team in the Tour. A school friend kindled Graham’s interest in cycling, bringing magazines to school, and they would pore over the exploits of Eddy Merckx and other famous names of the Tour. The two friends would also set off for cycle rides together, Graham usually having to borrow his brother’s bike as he did not have one of his own. He remembers one of his first rides being to Alderley Edge in Cheshire, which he thought was a really long ride!

As his interest in cycling grew he decided to join a club, as he was now the proud owner of a new sports bike. On his visits to Fallowfield Stadium he had heard the name of the Abbotsford Park Road Club mentioned many times and when he discovered the clubroom was quite near his home he decided to join. During the winter months he set off with the club on their Sunday rides to various parts of Derbyshire and Cheshire but his interest lay with racing so early in 1973, with help and advice from Malcolm Firth, he rode in one or two schoolboys races on closed circuits; he also remembers one cold day when he rode his first club time trial over ten miles. It was a very hard ride.

During his first year of racing he had no success and remembers being lapped frequently during the circuit races but this didn't stop him from enjoying his new sport. By 1974 he had reached 16 years of age and was classed as a junior and was permitted to race on the open road. With the assistance of his clubmates he had now started training but this seemed to have no effect on his racing performances until May when on a Saturday he managed 5th place in a circuit race and the following day won a handicap race at Macclesfield. HIS FIRST VICTORY !!!!.

As a junior he frequently raced against senior riders in mixed races and over longer distances than he had been used to as a schoolboy. He was finding life very hard. He also suffered from a problem well known to cyclists - having his entry to races returned due to his lack of performances. He had entered for several races in the Peter Buckley series, which was a season long competition for junior riders, but it was not until near the end of the season that he was successful and had his entry accepted for the two final races in the series. One race was on the Torside Circuit, near Glossop, and the other was in the Northeast of the country. He finished second in both races and this brought his name to the attention of the British Cycling Federation and he was selected for the Great Britain Junior Squad with the possibility that he might ride in the Junior World Championships in Lausanne, Switzerland, the following year.

Ken Cope, one of the older members of the club with a great interest in Road Racing, took Graham under his wing, giving him encouragement, advice and providing transport to races. Ken quickly became Graham’s number one fan and he was overjoyed when Graham was selected for the Junior Squad. 1974 came to an end with the exciting prospects of international racing and the realisation that a serious training programme would be needed. He spent the winter in the gym, circuit and weight training and road training on the roads near Trafford Park under the watchful eye of Malcolm Firth. Some of his training was done with First Category riders and by listening to them he started to learn some of the skills and tactics needed for road racing. He spent several weekends with other members of the Junior Squad training under the control of Tom Pinnington, the B.C.F. Chief Coach. During the summer the squad spent a week at the Isle of Man where they raced with the seniors in the Viking Trophy over 75 miles, the same distance as the World Championships. Graham finished in 5th position, which confirmed his selection for the Championships.

The Junior Championship race was Graham's first time abroad and the first time he had ridden with fields of over 150 riders. To his surprise he slotted in right away, was not troubled by the large bunches, and learned the first lesson of road racing - always stay near the front of the bunch. He finished 22nd in the World Championships and on his return home won 15 races during the rest of the season. Even though Graham was now moving into a higher echelon it didn't stop him from competing in his club's events when he had the time. Club founder member, Gerry Gorman, tells of one occasion when Graham turned up for an evening ten mile time trial and without bothering to change rode round in 22.57. "He didn't even seem out of breath", says Gerry.

Graham was also discovering he had a special talent for climbing hills, the steeper the better, a talent which would serve him well later in the Tour de France. He won both the Circuit of Kinder and the Oldham Century Mountain Time Trials, the Kinder event by over 4 minutes - not bad for a junior racing against seniors! Very much against his will he was talked into having a go on the track at Fallowfield, the same track where he had gazed in wonder at the top sprinters in action. He took part in the Track League but never liked this side of the sport; still it didn't stop him from winning the club's pursuit championships and taking part in the National Championships at Leicester. Graham calls 1975 the year of the fourth place, for he was placed fourth in the National Junior Championships, fourth in the Peter Buckley Series, fourth in the National Pursuit Championships and fourth in the National 25-mile Championships. At the Abbotsford Park R.C. Prize Presentation at the end of the year he was awarded the Road Race Cup, the Pursuit Cup, the 25-mile Cup (With a time of 57.57) the Junior Championship Trophy and the Abbot of the Year Rose Bowl - and his Mum bought a new tin of Duraglit !!!

INTO THE SENIOR RANKS

By the time 1976 dawned Graham had decided that if he wanted to succeed at this sport he would have to take things very seriously. He intended to try his luck on the continent and planned to have a season in Belgium. Here again he was helped by Malc. Firth who discovered that Graham was too young to race in Belgium but the Dutch didn't stick to the rules too closely, so the plan was changed and Graham left home to race in Holland. Due to conflicting rules he was not classed as a senior rider abroad although he was a senior at home so, before leaving for Holland, he had to get his First Category Licence. This he did by winning enough points to become First Category in just FOUR WEEKS !!!.

His plan was to race in Holland from April to September and it took some courage to leave home and face living in a foreign country with no knowledge of the language. Dutch racing was mainly criteriums (Circuit races) but the sheer speed shocked him and he found life very difficult in the bunches. Although he never managed to win a race whilst in Holland he did win enough prize money to survive and returned to England at the end of the season much fitter and wiser than before. By 1977 he was 19 and could now race legally in Belgium so he planned another season abroad. Before leaving England he won the Grand Prix of Essex in mid-March, a win which earned him a full-page write-up in CYCLING magazine, then it was off to Belgium where he won a race during the first weekend. This was a great start.

Belgian races were mainly road races, which was much more to Graham's liking, and soon he found a number of other English-speaking riders so didn't feel as lonely. Again he found the speed of races much higher than at home but settled in quickly, winning 5 races during the season. He rode in 97 races and finished in 80 of them. Graham said that some English riders had accused the foreign riders of "ganging up" against the British but Graham never experienced this. "The races were always hard and fast" he said "but I had no problems with other riders". During his time in Belgium Graham had to return home several times as his win in the Grand Prix of Essex had earned him selection for the Peace Race (Warsaw-Berlin-Prague), the Scottish Milk Race, and the World Championships, which took place in South America. He found the Peace Race to be less difficult than he had expected but lost a lot of time with a bad crash; still it all added to his store of knowledge. He finished 5th in the Scottish Milk Race and the World Championships took place in the hottest weather conditions he had ever known. He finished in 35th position.

About this time he was offered a professional contract in Belgium but turned it down as he felt he could do much better for himself. 1977 ended with him being selected to ride in the Etoile Des Espoirs (Stars of the Future) Race in France. This was a five-day race for both amateur and new professional riders. One of the professionals could hardly be classed as new as he was Bernard Hinault who had already won the Liege-Bastogne-Liege and the Fleche Wallonne and had been a pro since 1974. On one stage, which was quite hilly, Graham broke clear with three other riders and stayed away to the finish, finishing in third place. He also held the King of the Mountains Jersey and did a good ride in the time trial, which Hinault won. He finished this race feeling he could hold his own against anyone; it was a great boost to his confidence. In 1978 he again rode the Scottish Milk Race, but had to retire due to sickness. He also rode in the Sealink International (2 Day) which started and finished in his hometown of Manchester. In this race he won the Prologue Time Trial, which took place on Barton Dock Road, part of his old training circuit. By now he was unsure just which direction his career would take but towards the end of the season this was resolved by a telephone call from Paul Sherwen. Paul had spent a year racing in France and had been offered a professional contract. He told Graham that the A.C.B.B. club in Paris were looking out for a top amateur to add to their team he suggested that Graham should contact them. He did so and was signed up. Once more he packed his bags and left home.

The A.C.B.B. (Athletic Club de Boulogne Billencourt) is not, as many people think, purely a cycling club but is a huge multi-sport organisation and the cycling section is just one part of the whole organisation. The club provided riders with bikes, clothes, accommodation, and expenses, leaving the rider with the job of training and winning races. There were stories that the club looked after their riders only when they were winning but quickly lost interest if they hit a losing patch. At first the club was for French riders only but in 1977 they changed their policy and started their 'Foreign Legion'. English-speaking riders who used this club as a stepping-stone to greater things were, 1977 Paul Sherwen, 1978 Graham Jones, 1979 Phil Anderson and Robert Millar, 1980 Stephen Roche, 1981 Sean Yates and 1982 Allan Peiper.

The trip to Paris was, for Graham, a nightmare. He travelled by bus and heavy snows made the journey never ending. He arrived at the pick-up point late to meet the manager Claude Escalon, who was very annoyed! The manager soon cheered up, however, when Graham won the second race he rode in their colours, the Grand Prix de Toulon.

Graham was now living the life, and had the training schedule, of a full blown professional and it was necessary as now he was racing against the best amateurs in the world. He had some problems with the language at first but quickly picked up enough to understand most of what was being said although it was some time before he found the courage to string words together to form sentences. By the end of the year he was getting by without too much trouble. To his surprise he found the A.C.B.B. didn't race their riders as much as he had expected and during his first season rode in about 65 races, winning 15 of them. The two victories which gave him most pleasure were both time trials. The Grand Prix de Nations, which is the world’s top time trial, starting and finishing at Cannes, on the Cote D'Azur. There are two sections in this race, amateur and a professional, both which take place on the same day over the same course. The race goes inland from the start into the mountains with plenty of steep climbs and twisting descents - a course just made for Graham. Although he won the amateur section of this race, which was a great feather in his cap, it was the less important Grand Prix de France, which gave him most pleasure. This race took place in the north at Boulogne over narrow country lanes and Graham beat many of Europe's best riders.

This sort of success was getting him noticed and with the season only half through he was approached by the manager of the Peugeot Professional Team with a good contract on offer. As Graham was leading in the season long competition, the Merlin Plage Trophy, he agreed to sign for Peugeot only on condition that he could complete the season as an amateur, as there was a lot of prestige in winning this trophy. 1978 came to a perfect end when he won the trophy and was named the top amateur in France. His dreams of riding in the Tour de France had come a step nearer.

THE PEUGEOT TEAM - 1979

After spending the winter at home, where he rode several hours each day building up a huge total of miles in training, it was off to the South of France to meet all the other members of the Peugeot Team. There were a total of 22 riders in the team and Graham was one of four new signings. Pascal Simon was another "new boy" whom Graham had met before many times in amateur races. He had also crossed paths frequently with another member of the team, Jean-René Bernaudeau, and a deep friendship developed between the two, a friendship that lasts to this day. Bernaudeau was the man all France thought would win the Tour de France but he didn't quite live up to expectations. Although he had many great wins to his credit he never managed the big one. The leader of the team was Hennie Kuiper with Vandenbrook the leader for single day races. Another member of the team, but nearing the end of his career, was Bernard Thevenet who had won the Tour de France in 1975 and 77.

The first few weeks were spent training but instead of the cold and damp of a British winter it was the warm sun of the Mediterranean - much nicer! Graham’s first race as a professional was the Grand Prix St. Raphael. This was a single day event over a very hilly course. There were about 150 riders and, keen to impress his new boss, Graham finished in second place. The next few months were spent training, racing and getting to know his teammates. He now had little trouble with the language and no problems being understood by the others. He was not expected to ride in the Tour de France in his first year as a professional so, as the other members of his team prepared for the biggest event of the year, Graham returned home to England where he rode in a few races and was featured in the Manchester Evening News. He followed the news of the Tour in the papers, Bernard Hinault winning the 25-day race (his second victory) in masterful style.

On his return to France, and keen to do well, Graham was struck down with some mystery illness, which ruined the rest of his season. He was still racing frequently but without much success and was glad when the season came to an end and he returned home for a rest before the start of training for 1980.

Graham always says that training starts on January 2nd, with Christmas and the New Year out of the way. So on January 2nd 1980 he set off to meet Paul Sherwen at Knutsford for a few hours of steady riding. It was cold and frosty with ice on the roads, near Mobberley he hit a patch of ice and crashed to the ground, the pain in his leg telling him it was more than a simple tumble. At hospital he was told his leg was broken and he would be in plaster for several weeks. This was a disaster and he fretted at the loss of training. As soon as the plaster was removed he tried to make up for lost time but there were still more problems ahead for he started to suffer with his knee which swelled up and became very painful. Back at the hospital he was told an operation would be needed but there was an 18 months waiting list. He could see his new career as a professional racing cyclist in ruins. The only way out was to go in hospital as a private patient, which he did, although it cost a great deal of money. The operation was a complete success and he had no further trouble from his knee. As soon as the dressings were removed it was back to France and into training with a vengeance and was racing by mid April. Three weeks later his manager gave him the news he had been dreaming about. He would be riding in the 1980 Tour de France! Hennie Kuiper would be team leader and all other members of the team would be helping Kuiper in any way they could.

The Tour would be over 3949 kilometres (2452 miles) spread over 25 days and there would be 130 starters. They would face both the Pyrenees and the Alps before the finish in Paris. Graham had raced before in the Alps but this would be different, as they would be racing for two weeks before reaching the Alps. As was to be expected, Graham found the Tour very hard but so did many other riders. Instead of the hot weather usually associated with the Tour de France it rained and was very cold. Many riders had slimmed down, losing every ounce of superfluous weight, and they suffered as the cold attacked their legs. Many fell by the wayside, including the race leader Bernard Hinault, who retired at Pau, much to the disgust of the French press. Graham’s friend, Bernaudeau, was another who called it a day, but Graham found the weather much as it was at home and was quite used to it. He was doing a fantastic ride and during the final week was all set to finish in the first ten. Unbelievable in his first Tour. However, he was struck down with sickness and, although he struggled on, lost a lot of ground to finish at Paris in 49th position, but still a great ride.

What were Graham’s feelings during his first Tour de France? "As the Tour progresses" he said, "You feel sick and tired of the same routine day after day and you look forward to the end. However, when it comes you have a feeling of anti-climax and you think. God! It’s all over"

There is still plenty of racing to be done after the Tour as every village in France invites the stars of the Tour to ride in their local race. This is the way that many riders earn their wages, as a good ride in the Tour will ensure plenty of starting money at the races. In addition to the local races Graham found the end of his season coming good with a second place in the Grand Prix D'Isbergues, a single day race in northern France, and good rides in the Grand Prix Fourmies, the Paris - Brussels and the Paris - Tours. He closed his season with 11th place in the Tour of Lombardy in Italy, the race known as "The Race of Falling Leaves". His season ended in October then it was off for two weeks lying on a beach in Spain - WITHOUT HIS BIKE! He wintered at home again going out on his bike twice a week until the New Year when it was back to his usual punishing training routine.

1981 was a full season without any serious problems and Graham rode in more races than any other member of the team. Hennie Kuiper had left the team and Australian Phil Anderson had joined. Graham rode all the early season classics including the week long Paris-Nice (the "Race to the Sun). Most years he rode the Paris-Roubaix. This race was one of the most popular with spectators but not with the riders as it took place over some of the worst roads in Europe, smashed bikes and crashes being the norm, little wonder that it is known as "The Hell of the North". This was not Graham's type of race but he rode in order to be available to help his team mates by giving up his wheels when necessary. He usually called it a day about 50 kilometres from the finish. He had a good ride in the Tour of the Mediterranean (5 days), finishing in second place and beating Bernard Hinault in the overall result as well as the in the Mountain Time Trial. His biggest disappointment was during the Criterium International (2 days). The first day was a 130-mile road race, which was won by Hinault. The second day was in two parts with a very hard road race in the morning and a time trial in the afternoon. There was no doubt that, after winning the first stage, Hinault was expected to win overall but Graham had other ideas. There were several tough climbs during the second stage and Graham felt that it was just made for him. He attacked early in the race and Hinault tried to go with him but was unable to do so, "It is very satisfying to drop Hinault!" says Graham, with a smile! He powered away building up his lead and going hard, by the penultimate climb, he was thinking that a good time trial would win the race for him. On a steep descent a television motorcycle failed to take a bend and crashed right in front of him. As he was moving so fast he could do nothing and fell off, sliding along with the motorcycle. By the time he picked himself up, battered and bleeding, and put his bike to rights he had been caught by a smiling Hinault and his chance had gone. Graham had won every Prime (hillclimbing prize) and felt that, with luck, he could have won the race. His near victory had proved that Graham was going well and was ready for his second Tour de France.

This year the Tour was slightly shorter at 3766 kilometres (2338 miles) but still over 25 days, and there would be 150 starters. Jean-René Bernaudeau was the team leader. But it was Phil Anderson who surprised everyone by taking the Yellow Jersey off Hinault. In the Pyrenees Bernaudeau went through a bad time and a number of times Graham and other Peugeot riders had to drop back to help him. On the 19th day of racing, which was the longest stage at 143 miles, from Morzene to the summit of Alp d'Huez (the climb with 21 hairpin bends), Graham was, again, called upon to drop back to assist. This time it was Anderson who was in trouble. Hinault had regained the lead but Anderson was in second place. In this stage the riders faced four severe Alpine mountain passes (Hors Catégorie) and Graham was with the leading group, when news of Anderson reached them. The Team Manager instructed Graham to go to his assistance, he had to wait several minutes for Anderson to catch him then coax him up the next couple of passes, but it was soon clear that Anderson was finished so Graham left him and set off to try and pull back his lost ground. By the start of the Alp d'Huez climb he had caught the second group but, by the finish, he had still lost a lot of time and dropped down the General Classification. Anderson, however, finished 17 minutes behind and dropped from 2nd to 19th position. In spite of all his team duties, Graham reached the Champs-Elysees in Paris in 20th position overall and his number one fan, faithful Ken Cope, was waiting to cheer him over the line.

How did Graham feel when instructed to drop back to help other members of the team? "You just do it, it’s part of your job", he said, "You are part of a team” The Peugeot Team won the team prize and, therefore, rode the Tour in Yellow hats. Graham tells you, with a smile, that he has worn yellow in the Tour - but only a yellow hat. Once more, after the Tour, came the round of local races and, by now, he was being recognised by the public and chased by youngsters with autograph books. He had set up a home in the north at Lille, but spent little time there due to his racing commitments. Still he felt it was important to have a base to come home to. Towards the end of the season Graham was dog-tired and looking forward to a rest but this was not to be. The manager pressed the team into riding the Tour de L'Avenir (14 days) by offering extra bonuses. This race took place in September and was won by Pascal Simon and the team finished the year with a lot of money in their pockets but totally exhausted. During this year he had raced more than any other team member, 140 days of racing with most days over 100 miles. With hindsight he thinks he was racing too much and should have been more like Robert Millar who refuses to race in events which don't suit him. This heavy workload was to have its effect the following year. A short holiday away from his bike, then it was time to start training for the new season. Little wonder that he felt shattered and below par.

CHANGING TEAMS - 1982

On his return to France he could still feel the effects of the previous hard season and yet the year started with a bang in the early classic, Het Volk, in Belgium. The race had been hard and fast and a small group had built up a lead but, in the closing miles, the race came together again. In the confusion Fonze de Wolfe sprinted away and the rest were hot on his heels. With, perhaps, two or three kilometres left to race Graham decided his time had come and put in a blistering attack. He found himself a few yards clear, in no-mans-land, between de Wolfe and the high-speed bunch. With the sprinters breathing down his neck he hung on but is the first to admit that he was running out of steam in the final few yards. De Wolfe won the race with Graham second and it looked as if it was going to be a good year but Graham calls 1982 a non-event. The rest of the season was a disaster and he felt he would never get going again. He was racing regularly and doing plenty of hard work for the team but it was all a great effort so it was not surprising that he was not selected to ride in the Tour de France.

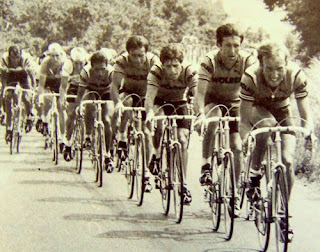

He came home while the Tour riders toiled around France, riding in several races and winning the Tour of Delyn in North Wales. After a short rest in Spain he returned to the team with low morale. This feeling must have spread to other members of the team for several riders, including Bernaudeau, were thinking of leaving the team for pastures new. Towards the end of the season Bernaudeau signed a contract with Wolber (cycle tyre maker) and Graham and several other Peugeot riders joined him.

After such a poor year Graham hoped that the change of team would put some interest in his life and came home, at the end of the season, with high hopes. During the winter he felt a great surge of keenness and was soon training again but decided to try something new. Instead of the usual hours of road training, building up a huge total of miles, he took to running and circuit training, feeling that anything which kept his heart and lungs working hard would keep him fit. When he started racing again, early in 1983, he had hardly one thousand miles in his legs, far less than usual. By February he was racing regularly and his newfound keenness showed in his results for he did well in almost every race. With 5th place in the Tour of the Mediterranean and 9th in the Paris - Nice all seemed back to normal. But, when racing in Belgium, a bad crash put him out of action for several weeks so he started his first, and only, ride in the Tour of Italy (22 days) not fully fit. Even so he enjoyed the Giro d'Italia and finished the race in 26th position.

Soon it was Tour de France time again and, once more, he was back in the team. The Tour distance, this year, was 3757 kilometres (2333 miles) over 23 days with 140 starters. Now he felt more professional in his approach and rode simply as a team rider helping Bernaudeau in any way he could. He finished in 69th place and felt he had ridden well within his capabilities and was satisfied that he was capable of riding two major Tours in the same year without too much trouble. Just as fortune was smiling on him he had a crash in September, breaking several ribs, which put him out of action for some time. Then Wolber announced they were pulling out of sponsorship but again Bernaudeau came to the rescue with a deal with Système-U, a supermarket chain, finding places for most of the Wolber Team. Bernaudeau could have gone to any of half a dozen top teams, and would have taken Graham with him, but he didn't want to leave the other riders in the lurch. System-U was a low budget team and didn't seem to have much of a future but with Wolber pulling out so suddenly, there was little choice. At the end of the year Graham came home wondering what 1984 held in store for him.

After winter training he returned to France in April only to be knocked off his bike, by a car, and was out of action for six weeks. This caused him to start the 1984 Tour de France far from fit and demoralised. How he suffered this year, in contrast to his confidence of the previous Tour. Day after day he dragged himself over the mountain passes but with about one week to go, he knew he could continue no longer and gave up the struggle. He will never forget the shame and distress he felt, at this time, as he waited to be picked up by the Voiture Balai (the last vehicle in the race convoy) That evening next to his name on the result sheet was the single word - Abandon. As expected, System-U pulled out at the end of the year and Graham felt sick and tired of it all. He needed a home life, some social life and was fed up of travelling all round Europe. It was time for a change. Graham did a lot of thinking during the winter and decided that, as the British professional scene seemed to be improving, he would try for a place with a British team, which would allow him to live at home.

BACK HOME

He signed for the Ever Ready/Marlboro team for 1985 riding with John Herety, Steve Fleetwood and Gary Sadler. He enjoyed this year at home. Life was easy, the races were shorter and slower, and it was like being on holiday. He had quite a good season but at the end of the year, Ever Ready pulled out and he realised what a big mistake he had made to come back to Britain. Had he stayed in Europe he felt sure he could have arranged a contract with a team in Belgium, Spain or Italy but after a year away he would be forgotten, his past successes would count for nothing. In 1986 a bright cloud came on the horizon in the shape of the ANC/Halfords Team and Graham was signed up because of his experience in the Tour.

This was a new team with big ideas. They planned frequent sorties into Europe building up a top team with the aim of preparing to ride in the Tour. It seemed too good to be true, was it possible he would ride in the Tour again? The Team Manager talked of a British rider winning the Tour de France - Graham took this with a large pinch of salt!

The Team Leader was the effervescent Liverpool rider, Joey McLoughlin, and the team rode several races abroad also the Milk Race and the Kelloggs Tour, and had a lot of success. Graham felt the team was trying to do too much too quickly and was horrified when, in 1987, it was announced they would ride in the Tour de France.

"We were just not ready", explained Graham. "To prepare for the Tour it is necessary to have many long, hard stage races in your legs, it is the only way to build up the deep-down reserves needed. We were not up to facing 130 miles a day for four weeks". For the ANC/Halfords Team the 1987 Tour de France was a disaster. The full story of their suffering is told in Jeff Conner's book WIDE EYED AND LEGLESS. They were lambs in the lion’s den, they were slaughtered. For a second time Graham had the humiliation of having the word - Abandon next to his name.

Full credit to the members of the team who managed to hang on to the finish at Paris. Adrian Timmis finished in 70th place and Malcolm Elliot finished in 94th position, most of the others fell by the wayside. To add insult to injury their manager walked out on the team part way through the Tour and the team had not been financed since July. The team that had promised so much turned out to be a flash in the pan.

For 1988 Graham managed to get a contract with Emmelle, but he admits his heart was no longer in it. "I was kidding myself", he says. "I was not interested in training and hoping I could carry on with the residue of fitness from more successful years" He recalls his last few races and spectators would look at him and he could see the question in their eyes "Did this guy really ride in the Tour de France?" At last the truth had to be faced - it was all over.

He rode his final race and the dream had ended. His bikes, all equipment and team clothes were sold. He didn't even keep one cycle to use for Sunday afternoon rides; he had severed all connections with racing. It was amazing that someone who had lived, breathed and slept cycling for so many years could cut it out of his life so completely. He didn't apply for re-instatement as an amateur as he had no intention of racing, ever again. "After racing at such a level I could never ride in a local 'fish and chip' race" he explains.

WHAT WENT WRONG?

Graham admits that he made mistakes. His biggest mistake was to leave Europe and return to Britain. He feels that he still had several good racing years left in his legs. He had lost heart and he is certain that the reason was that he was over raced. Graham was best at stage races over several days or weeks and disliked the single day events. "If I had started my season later and rode fewer single day races I am sure I would have lasted longer" he said. He blames only himself for this. "I should have stood my ground and refused some races, as Robert Millar did, it would have been so much better for my career. "I felt flattered when I was asked to race so often, I thought they appreciated me", he says. "I knew I would never be a Hinault or a Fignon and win the Tour de France, but I was capable of being a top class team rider who could ride all the major Tours without killing myself". Both Jean-René Bernaudeau and Phil Anderson had learned the value of having Graham in the Team, riding for them.

LIFE AFTER THE TOUR

For the first time in his life Graham had to look for a job and set himself up in business importing A.T.B. bikes into the country but the call of the Tour de France was too strong to resist. Each year in July he takes a month off his job and returns to the Tour, not as a rider but as a driver of one of the official Tour vehicles. He drives British journalists Stephen Bierley of the Guardian and Geoffrey Nicholson of the Observer who are, no doubt, pleased to have an ex-rider to advise them and Graham’s ability to speak fluent French comes in very handy. He is also a commentator for the Eurosport TV programme.

These jobs involve him in many hours of driving but allow him to meet up again with his friends connected with the Tour. Each year he meets Thèvènet, Bernaudeau, Anderson and Paul Sherwen and they drink many glasses of wine, re-live many memories and dream of what might have been.

With many thanks to Graham for the long interviews - Duncan

© 2010 Classic Lightweights

Commenti

Posta un commento