When President Trump inaugurated the 1989 Tour de Trump

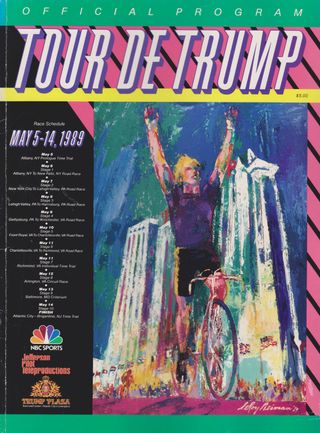

The cover of the 1989 Tour de Trump program

(Image credit: Tour de Trump)

By Peter Joffre Nye published April 29, 2020

Extract from Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing, second edition

Donald J. Trump, the 45th president of the United States, is a controversial figure, but decades ago he put his name behind a professional cycling event.

Riders from more than 12 nations competed in the 837-mile cavalcade through five states in the 1989 Tour de Trump. In this excerpt from the book Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing, second edition (University of Nebraska Press), Peter Joffre Nye describes how the race came to be.

Billy Packer, familiar to millions of basketball fans for commentary on network television college basketball, had an idea to share in late 1988 with New York real estate developer Donald J. Trump. Through business contacts, Packer wrangled a two-minute meeting in Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue to make a pitch.

Andy Hampsten's dramatic Giro d'Italia victory that spring, following Greg LeMond's 1986 Tour de France triumph, impressed Packer. Hampsten's 7-Eleven teammate Davis "Cash Register" Phinney had recently won the 1988 Coors International Bicycle Classic, America's national tour in Colorado and western states. The classic's title sponsor, the Coors Brewing Company, announced after Phinney's triumph that it withdrew title sponsorship for 1989, to sponsor a new Coors Light Cycling Team built around LeMond. Packer sought to fill the void by creating a new national tour – what he called the Tour of New Jersey.

Ushered into the Trump's inner sanctum high up in Trump Tower, he asked what the realtor thought about promoting an international bicycle race that could grow to rival the Tour de France. "I said it could start at one of his properties in New York City and end at one of his casinos in Atlantic City," Packer recalled in a press conference before the start of the race. Aware that Trump's name adorned everything from a six-level yacht, Trump Princess, almost as long as a football field, to the 566-luxury-room Trump Plaza Casino and Hotel in Atlantic City, Packer said: "I told him we could call it the Tour de Trump."

Trump winced from behind his desk. "You've got to be kidding," he said. He paused and gazed out his office window, offering a spectacular view of Manhattan Island. Five years earlier he had spent more than $10 million for the New Jersey Generals football team and players in the short-lived United States Football League. He garnered more publicity in the USFL's single season than in a decade in real estate. Ten seconds after Packer's pitch, he said: "It's so wild, it's got to work."

Eight months later, on May 4, 1989, the realtor sat at a table in a hotel conference room in Albany, New York alongside LeMond and a half-dozen other cyclists as brilliant and high-priced as the crystal, marble, and brass adorning Trump's four-star Atlantic City hotel. He faced 120 media filling the room to standing room only from around the United States, Canada, Mexico, Colombia, Australia, and Europe.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!Contact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

The realtor had allowed his name to be used in the Tour de Trump without his Trump Organization investing, unlike other sponsors, from Gatorade to Proctor & Gamble, from Oldsmobile to BMW, that wrote six-figure checks. As a result, the Tour de Trump offered a purse topping $200,000 and $50,000 to the winner. The 837-mile itinerary over eleven days, from May 5 to 14, began in Albany, wended south to Richmond, Virginia, then turned north to Atlantic City and concluded on the famed boardwalk in front of the Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino.

A glossy seventy-two-page Tour de Trump souvenir program featured bright cover art by pop artist Leroy Neiman. It depicted a cyclist modeled after Davis Phinney, in his trademark finishing pose, arms thrust skyward like goalposts, in front of a towering hotel and casino. The glitzy publication opened with a Welcome from Trump, his portrait photo, and his signature writ in a broad nib, vertical strokes sharp like shark teeth.

'My name has turned out to be a great asset'

Asked in the press conference if he would consider changing the name to Tour d'Amerique, Trump smiled and shook his chestnut-brown mane combed in a 1950s Tab Hunter style. "We could if we wanted to have a less successful race," he replied, igniting a burst of laughter from the exuberant Fourth Estate.

Trump grinned around the room, relishing the attention. Unlike cyclists and managers in team warm-ups or sports journalists dressed like they were in a laundromat washing clothes, he stood out in a white shirt with point collar, gold cufflinks, a pink tie, and a boxy dark pinstripe suit. At 6 feet 1 and age forty-three, he carried himself like a former first baseman.

"My name has turned out to be a great asset," he declared as cameras flashed like an electrical storm trapped inside a conference room. Trump sat by Belgian sprinter Eric Vanderaerden of Panasonic, a team directed by Dutch six-day cycling legend Peter Post. Jan Gispers, director of the Dutch PDM squad, announced that he skipped the Four Days of Dunkirk in France for the Tour de Trump: "We knew this would be a really professional race. In Holland we saw a documentary on television about Donald Trump."

Trump and Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino partnered with NBC Sports and Packer's Jefferson Pilot Productions to produce the event. "The Trump Plaza Casino is the number-one casino in Atlantic City," Trump boasted. "Trump Apartments in Manhattan have the highest rental rate per square foot in New York City. I don't want to have a race with my name on it that is not a success."

He waved a manicured hand to the scrum of reporters, photographers, and network camera crews. "My name is the difference between a press conference like this and holding a press conference and speaking to only one reporter." He admitted surprise when Packer proposed the name Tour de Trump. "Truthfully, I almost fell out of my seat when I heard it."

The Coors Light team, captained by LeMond, on a special arrangement for U.S. racing when not in Europe competing for a Belgian team, was among the eight pro squads and eleven amateur crews of six riders each. They composed a field of 114 starters from fifteen countries. A pro team from Italy had racers from the Soviet Union, marking the first time that a Soviet professional squad in any sport competed in the United States. The U.S. Cycling Federation (predecessor to USA Cycling) fielded two USA national teams—one included a triathlete from Texas, Lance Armstrong.

New York Governor Mario Cuomo had the honor of official starter, standing before the peloton in front of the 19th Century gray stone Empire State Capitol. He set the riders and support caravans off for the Tour de Trump Stage 1 road race, on their way to a serpentine route through five states.

NBC Sports dispatched a crew of seven to program two-hour Tour de Trump specials on the two Sunday afternoons, supplemented by ESPN coverage from Monday through Friday. The 7.5 hours of national TV topped what CBS had beamed for the Tour de France. NBC hired LeMond, in a blue-and-white Coors Light jersey, to record fifty spots for NBC affiliates.

In the race, flu hampered LeMond. He took advantage of the prologue and two more individual time trials to hone an aerodynamic position on an archetype time-trial bike. It featured a down-sloping top tube to lower his center of gravity, a solid-disk rear wheel (less drag than a spoked wheel), and novel aero handlebars narrowing his profile and tucking his arms close to his chest like a downhill skier.

The Tour de Trump rolled over undulating and twisting secondary roads between cities, where crowds were consistently large. Bystanders held up cardboard posters. One said: "Welcome bikers, welcome Donald Trump, welcome NBC." Another read, "Send money, Donald." Giggling school children stood in a line facing the street and held posters, each with one letter, that spelled: "We Are Out Standing in Our Field."

Phinney burst ahead of the galloping pack to sit up, face beaming, arms forming goal posts, before enthusiastic throngs in Baltimore's Inner Harbor and near the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia's office enclave of Crystal City.

The event drew an audience of more than a million, doubling all cycling events at the LA Olympics combined, and generated unprecedented Northeast and Mid-Atlantic local coverage. Winner of the Tour de Trump was Dag-Otto Lauritzen of Norway on the 7-Eleven team. His team snatched five places in the top ten. For the brass of the Southland Corporation in Dallas, parent company of 7-Eleven, the media splurge of their brand justified eight years of sponsorship.

Trump in his suit joined Lauritzen in a red-green-and-white 7-Eleven jersey on the winner's podium in front of the Trump Plaza Hotel and Casino. Mogul and cyclist waved to the crowd. News hounds concluded the event exceeded all expectations. Plans were underway for a bigger Tour de Trump in 1990.

I was walking with an aide from the Trump Organization in the Trump Plaza and Hotel down a crowded carpeted hall when the aide spotted The Donald walking toward us. The aide called to him and made introductions. I was wearing the money-green Tour de Trump media badge around my neck. The instant our palms touched, he pulled me close to him and asked in a soft voice, "What do you do?"

"I'm a writer, Donald."

The future forty-fifth U.S. President threw my hand down, hard enough to bounce off the carpet if it weren't attached to my arm, and he walked away.

The 1990 Tour de Trump went 1,130 miles over eleven days and drew a larger field. Afterward, the DuPont Corporation took over as title sponsor for the Tour DuPont, held through 1996.

The cover of Heart of Lions, second edition

(Image credit: University of Nebraska Press/Graham Watson)

Excerpted from Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing, second edition (University of Nebraska Press), by Peter Joffre Nye.

The book will be released on May 1. Save 40 per cent with Code 6AS20 on the publisher's page:.

Nye is a prize-winning author of nine books, magazine editor, and a journalist who has contributed to the Washington Post, USA Today, Sports Illustrated, and Humanities Magazine.

Peter Joffre Nye is author of the updated second edition of Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing (University of Nebraska Press).

Commenti

Posta un commento