How the Detroit Pistons came to be known as the Bad Boys

by DAN HOLMES on APRIL 27, 2016

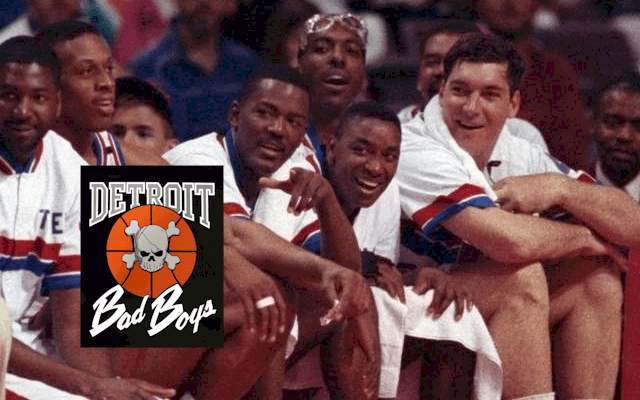

It never bothered the Detroit Pistons that they were called the “Bad Boys.”

Leave it to the owner of a football team to help brand a basketball team as a bunch of thugs.

Actions like that were second nature for Al Davis, the owner of the Oakland Raiders and a self-described “maverick.” But the story of how the Detroit Pistons became known as the “Bad Boys” and cloaked themselves in the dark garb of villains, starts before Davis sent a crate of Raiders gear to Detroit head coach Chuck Daly.

The story of the Bad Boys also includes a Detroit native who scratched out the Bad Boys logo for his silkscreen t-shirt company and saw it explode in popularity, so much so that Nelson Mandela once wore a cap with the logo on it.

After the 1988 NBA Finals, in which the Pistons lost narrowly to the Los Angeles Lakers in seven games, the NBA entertainment department edited and produced their annual video for each team. These tapes were sold mostly at retailers and were available in VHS (yes, that’s what we watched back then). Some bright copy editor decided to call the Pistons’ 1987-88 season video “Bad Boys.” The rest was history.

But wait, not so fast. How did they arrive at the name “Bad Boys” and why did it take off? Why did thousands and thousands of fans in Detroit and around the country start wearing “Bad Boys” merchandise?

The answer goes to the heart of who the Detroit basketball team was in that era. It goes to the heart of their floor leader, a Chicago kid who had a serious case of “little man syndrome.”

Why the Pistons were considered “Bad Boys”

Isiah Thomas was the unquestioned leader of the “Bad Boys” Pistons, and he branded the team with his personality.

Isiah Thomas was more than just a point guard, he was the life blood of the Detroit Pistons from the first time he stepped onto the hardwood as a rookie in 1981. Thomas was a marvel with a basketball in his hands: he might pass it, he might shoot it, he might dribble it like he was a member of the Harlem Globetrotters. Most importantly for the success of the Pistons, Isiah was a floor leader. He had that leadership thing inside him and it wouldn’t turn off.

Growing up in a large family in the worst neighborhoods of Chicago in the 1970s, Thomas developed a tough outer shell, a biting tongue, and a furious competitive nature. He wasn’t content with just winning, he wanted to destroy the competition. As a little guy on the courts in the Windy City he had to learn how to go into the land of giants under the basket and score his points. By the time he got to the NBA as a 20-year old, he was tough enough to manage the bumps and bruises that came with competing in “The Association.” In some ways, the NBA was tamer than what Isiah was used to.

Through his Hall of Fame basketball skill and drive, Isiah pushed the Pistons up the NBA ladder. So that, by the time of the 1987-88 season, with an excellent cast built around him, Detroit was one of the best teams in the game. But as anyone who knows Detroit knows, the city doesn’t come by respect easily. Detroit really has to earn its respect. There’s always someone who wants to ridicule and diminish the city. But Isiah’s toughness wasn’t going to let that happen.

Guided by coach Chuck Daly, a cool customer whose “Daddy Rich” appearance and well-coiffed hair concealed a fierce determination, and under the floor management of the point guard they called “Zeke,” the Pistons assumed the personality of their leadership. It extended to the front office too: general manager Jack McCloskey, the hoops genius who assembled the team, was a confident man who burned to compete and win on the biggest sports stage. McCloskey had commanded landing ships for the U.S. Marines in World War II. He was a tough man.

Under Daly’s direction, the Pistons adopted a philosophy of “94 feet defense.” The idea was that the team would defend everywhere on the court. They wanted to make it difficult for opponents to set up their offense. Up until that time, most NBA teams ran back on defense and allowed the offensive team to set up and run plays. It was basically a gentleman’s agreement: there were certain things that a team didn’t do, and one of them was to disrupt the flow of the game. But the Pistons didn’t care. They pressured, bumped, and agitated unlike any other team ever had. As a result, they earned a reputation for being “dirty.” While they never led the league in personal fouls or technical fouls in that era, they did lead the league in the unofficial categories of “hip checks,” “forearms,” and “icy stares.” Soon, Isiah and his teammates were the most hated team in the game.

How the Pistons gladly accepted their role as villains

The supremely confident and ultra-competitive Bill Laimbeer had no problem being physical on the court.

Given Isiah’s nature, when he saw what the NBA had titled the team video he was not shocked or offended. Instead he lathered on one of those famous “Cheshire Cat” smiles that he was famous for. Only Isiah could simultaneously look innocent, devilish, playful, sarcastic, happy, and insane at the same time.

“I guess we’re the Bad Boys,” Isiah chirped when asked about the name in the offseason.

“[I’m] not sure about the name,” coach Daly said, “but I know our team isn’t going to back away from it.”

And that’s one of the secrets about the Bad Boys. If the Pistons themselves hadn’t embraced the name, it never would have stuck, and it wouldn’t have become as iconic as it did. Everyone who knows anything about Detroit or basketball and NBA history knows who the “Bad Boys” are, and that’s only because Isiah and Bill Laimbeer and Rick Mahorn and the others were happy to be those guys.

During training camp before the 1988-89 season, Davis, the principle owner for the Raiders, and a man who never met a bad dude he didn’t like, instructed his staff to gather tee-shirts, caps, and shorts emblazoned with the silver-and-black logo of the Oakland Raiders.

For years his Raiders had been the “trouble child” of the NFL, and Davis had butted heads with NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle so often that they shared the same chewing gum. Davis loved to see other teams have the guts to stand out and be different. He liked the swagger of the Pistons.

A camera crew was on hand when Daly, Isiah, and others first rifled through that box of Raiders merchandise sent by Davis. Immediately, some of the players started wearing the items in practice and even during pre-game. When the season started, some fans could be seen wearing Raiders caps and tee-shirts at The Palace of Auburn Hills, the new home of the team.

The NBA was not happy at first. They didn’t like the idea that their league would be celebrated for “rough” play and a “bad” image. But they quickly changed their tune.

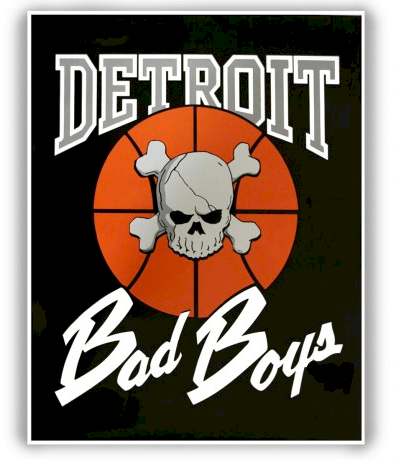

The Bad Boys logo

The Bad Boys logo was an immediate hit when it debuted during the 1988-89 NBA season.

The NBA has never met a marketing opportunity it didn’t like. When they saw basketball fans wearing NFL merchandise to NBA games, they knew they had an opportunity to make some money. But first they needed a hook. They couldn’t sell Raiders gear at the NBA venue in Detroit without having to jump through licensing hoops. They needed their own brand.

But before the NBA could pounce on the market, an enterprising Detroiter stepped in, a principle partner in The Athletic Supporter Ltd., a firm based in Farmington Hills. Billy Berris, who had once played hoops in the Motor City as a high school star in the 1960s at Detroit Mumford, put his imagination to work along with the pen of his graphic artist Robin Brant to devise a logo for the Bad Boys.

Obviously black and silver needed to be used (in a tip of the hat to Davis and the Raiders), so Berris decided on that and then added a skull and crossbones, because that’s some scary stuff. Brant added a nice touch by giving the skull a few cracks and then he placed it in the middle of a basketball with the words “Bad Boys” scripted beneath. The font chosen was somewhat reminiscent of what we saw from Michael Jackson on his “Bad” album a few years earlier, sort of looking like spray-painted graffiti.

For Berris, the job of creating a marketable Bad Boys image was a labor of love. His part in making the Bad Boys the “Bad Boys” may not be well known, but it was the flashing point for taking a team nickname and making it a cultural brand. It was fitting too that a Detroiter designed the logo.

For years the Pistons logo had been one of the least popular in the game. While some loved it for its simplicity (you can’t get much more simple than the team names scrawled on top of a basketball in team colors), others shook their heads at the bareness of it. Even today, the Pistons primary logo, which is largely unchanged from the 1980s, is considered one of the worst in the NBA.

Quickly, the Bad Boys image became immensely popular, especially with urban youth. In Detroit, kids were wearing it to show how tough they were. Jalen Rose, who later starred as a member of the “The Fab Five” for Michigan, embraced the Bad Boys brand as a teenager growing up in Detroit.

“I loved everything about the Bad Boys. I loved how they played and how they didn’t back down,” Rose recalled in an ESPN podcast in 2013. “They just went out and kicked the other teams’ butts.”

The Legacy of the Bad Boys

Detroit point guard Reggie Jackson wears a Bad Boys cap during the 2015-216 season.

The Detroit Pistons won NBA titles in each of the first two seasons they were known as the “Bad Boys,” but the glory of the black-and-silver and that label wore off sooner than many expected. Michael Jordan and his Chicago Bulls helped shape an image of a high-flying, athletic basketball team that didn’t need to be “thugs.” When the Bulls finally defeated Isiah and the Pistons in the playoffs in 1991, it was obvious that an era was ending.

But while Air Jordan and his Bulls might have acted like they had no respect for Detroit basketball, they did something that some didn’t notice at the time: they adopted the Bad Boys tough play. Without the Bad Boys changing the way the game was played in the 1980s and beating up on His Airness and the Jordanettes, there would probably have not been a Bulls dynasty in the 1990s.

Ironically, the Pistons themselves worked hard to dismiss the era of the Bad Boys. After Isiah retired prematurely due to an injury, and then Laimbeer and Dennis Rodman retired or moved on, the team’s “bad” core was gone. In the mid-1990s the team was building around a new superstar, Grant Hill, a squeaky-clean college star who played a lot more like Jordan than he did Isiah.

For the 1996-97 season the team unveiled new uniforms and a new logo. It was the beginning of what became known as “The Teal Era.” Gone were the red-white-and-blue colors of the Pistons’ championship teams of the late 1980s. Gone was any mention of “Bad Boys,” even though Joe Dumars was still putting up his rainbow jumper for the team. No, the Pistons were turning a page, and for some damn reason that meant burying the history of the best team in franchise history. The Pistons had won a title under a different logo and different “brand” only six years before, the bodies of the Bad Boys were barely cold, but the front office was shoveling dirt on an era.

The teal and purple logo, with a horse head that looked like a knight piece on a chess board, was never popular. Not with real Pistons’ fans. It was mocked, as it should have been. When the team switched back to the traditional red-white-and-blue color theme and logo for the 2001-2002 season, it coincided with a revival of success on the court. Thankfully, a few years later when they won a third NBA title, it was the old logo that adorned the jerseys worn by Chauncey Billups, Rip Hamilton, Ben Wallace and the rest.

The Bad Boys image has always lurked under the surface of the Pistons, and when the franchise returned to prominence in the early 2000s, advancing to six consecutive conference finals, you started to see some fans reviving their Bad Boys caps. It was as if someone gave them the green light to pull their Bad Boys t-shirts out of the bottom of their closets.

In 2014 ESPN’s award-winning documentary series aired a film on the Bad Boys, which was also released on DVD. The documentary reunited Thomas, Laimbeer, Rodman, Rick Mahorn, James Edwards, John Salley, Joe Dumars, and other members of the team. It was one of the highest-rated segments in the 30-for-30 documentary series. Its popularity has helped spawn renewed interest in the Bad Boys. Not just the team, but the logo too.

It’s safe to say that the Bad Boys will always be an important part of Detroit sports history and NBA history. The two-time champions were one of the greatest teams in NBA history, even if they are often overlooked and underrated. They vanquished every great team of their era: the Larry Bird Celtics; Magic Johnson’s Showtime Lakers; and the Michael Jordan-led Bulls, who were eliminated from the playoffs by Isiah and the Pistons three years in a row.

Unlike most other teams however, the Pistons of the Bad Boys era will live on for many years in more obvious ways. That’s because they have their own clothing line, and basketball fans, whether they rooted for Detroit or not, love the nostalgic image of that tough-as-nails team.

Copyright © 2021 Vintage Detroit Collection

All Rights Reserved.

Commenti

Posta un commento